Two slogan-covered boxes are bundled out of a van. People lie down on the road next to the boxes. Within seconds, the police are there. So are other campaigners protesting against the DSEI arms fair, which is being set up in the nearby ExCeL Centre. Within minutes, the four people lying in the road – Chris Cole, Henrietta Cullinan, Jo Frew and Nora Ziegler – have been arrested.

This small action, which took place on 5 September 2017, led directly to a ground-breaking legal judgement by the British supreme court almost four years later, known as Ziegler.

On 25 June 2021, the UK’s highest court changed the legal situation for civil disobedience by declaring that protests which are deliberately obstructive of legal activities can still be legally justified, depending on the circumstances.

One year on, the Ziegler ruling has had huge consequences for many British direct actionists, including the Colston Four (see PN 2659).

*

This Peace News supplement explores how the supreme court judgement came about, focusing on the experiences of the four Christian peace activists at the heart of the case.

To begin with, we should acknowledge that, by celebrating the anniversary of the supreme court decision in this way, we may strengthen some unhelpful tendencies.

There is a tendency among many activists, for example, to value arrestable action over less-visible kinds of work for social change.

Protest movements can also fall in with the mainstream media addiction to creating ‘heroes’ and ‘celebrities’ who are somehow better than the rest of us.

“I refuse to play along with putting a few activists on pedestals while ignoring all the people doing such hard work behind the scenes. I’m so sick of it.” - Nora Ziegler

This is something that Nora Ziegler, one of the Ziegler Four, wanted to highlight in our conversation. She said: ‘I refuse to play along with putting a few activists on pedestals while ignoring all the people doing such hard work behind the scenes. I’m so sick of it. I’m so sick of, in our movement, certain people being celebrated like heroes while other people are ignored. And that’s not just because I think it’s unfair or whatever. It undermines accountability: it lets the “heroes” off the hook of being answerable to the people who’re affected by what they do; it means the “heroes” don’t have to listen to other people’s experience of their actions. Our protests and organising work have consequences for other people and often there are tensions and conflicts that are hidden away when one side in the conflict is invisible.

‘For example, while I was taking part in protests and direct actions I was also living and working in a community supporting refugees. My activism could potentially endanger the community, for example if the police raided us. At the same time, living with refugees and migrants with no recourse to public funds also informed my activism and made me accountable to some of the most marginalised people in the country. But if my activism is taken out of context and celebrated by a movement that doesn’t know those refugees and migrants even exist then that undermines their power to hold me accountable.’

Earlier, I’d asked Nora how she felt when she first heard about the supreme court decision. I’d been struck by the lack of happiness or excitement in her reply.

Nora says: ‘Maybe my lack of excitement is because I think I do a lot more important and remarkable things; the stuff that no one ever sees, that won’t ever have a report written about it.’

Nora describes some of her feelings about the supreme court ruling: ‘I think it is a good thing, it is an important thing, but it’s just one among many important things that I do that no one gives a shit about... every time I cook in a soup kitchen, or every time I support someone at court, or every time I go with someone to an appointment about their immigration status, or have another boring meeting about running the Catholic Worker house....’

Nora goes on: ‘I devoted myself to that community, the Catholic Worker, I worked so hard looking after people, always putting everyone else’s needs before mine, and I also really struggle because of it. My mental health took a huge hit from that, as well. But I worked really hard, and I was good at it, you know. It bothers me that that kind of work – and I’m not the only person who does it – that kind of work is not valued.’

Nora continues: ‘Then people suddenly think that I’m an important person to talk to because my name is attached to a judgement that was achieved by other people, the lawyers. That judgement has so little to do with me.’

*

As Jo Frew, another of the Ziegler Four, says to me: ‘Our action wasn’t anything particularly different or special, it could have been anyone, it could have been any action that the CPS chose to appeal against.’

“We’ve helped uncover companies advertising everything from leg irons and gang chains to electric shock stun batons and cluster bombs [at the DSEI arms fair]”

Nora also says: ‘It’s very coincidental you know. It could have been any action that unfolded into these consequences. I think the credit, in any case, goes to all people who take direct action, in that it’s a really important part of movements for social justice. It’s not only the lawyers; people doing community-building, community organising, all play a part in it.’

With all these reservations in mind, PN is sure that this victory deserves celebration and that the story behind it is well worth telling.

*

The action which is at the centre of the supreme court’s decision took place during the run-up to DSEI 2017.

Over the years, there have been hundreds of arrests outside (and sometimes inside) what is often described as the world’s largest arms fair, whose full name is the ‘Defence and Security Equipment International’ exhibition.

Since 2001, the arms fair has been held every two years at the ExCeL Centre in East London – always accompanied by anti-arms trade and anti-militarist protests.

One of the reasons for the demonstrations has been the parade of dictatorships and human rights abusers invited to DSEI.

In 2015, for example, the DSEI before the Ziegler action, the arms fair hosted delegations from seven of the foreign office’s ‘human rights priority countries’: Bahrain, Bangladesh, Colombia, Egypt, Iraq, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

Campaigners arrested for protesting against DSEI 2015 issued a joint statement a few weeks later. They pointed out that ‘numerous buyers were invited to attend from regimes with a documented history of human rights abuses, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, including many actively engaged in illegal wars or occupations’.

*

I asked Jo what was the main thing she was thinking about in September 2017, in relation to DSEI. She answered: ‘I used to be involved in anti-capitalist stuff, the WTO [World Trade Organisation] protests and things like that. There could be something redeemable about a world trade organisation... or COP 26. There isn’t anything good that can come out of DSEI, in terms of peace and justice.’

She added: ‘Also, I live in a house of hospitality, kind of like a Catholic Worker, but smaller. We live with people who are refugees – some from oppressive regimes that use military equipment against their own people. So, when you know people, you know how much people struggle because of the arms trade, it adds a personal or interpersonal dimension to the politics and economics of it.’

*

There were important acquittals at the arms fair before the Ziegler case.

In April 2016, to take just one example, eight protesters who had blocked roads outside DSEI 2015 were acquitted. The eight blockaders were: Isa al-Aali, Angela Ditchfield, Lisa Butler, Thomas Franklin, Javier Gárate, Susannah Mengesha, Luis Tinoco Torrejon and Bram Vranken.

Their legal defence was that they were acting to prevent the illegal sale of torture equipment and weapons to countries that abused human rights. (see PN 2594 – 2595)

Before human rights observers were banned from the event, they found illegal advertising activity at every DSEI from 2005 to 2013.

The Amnesty International arms trade expert, Olly Sprague, wrote in 2015: ‘we’ve helped uncover companies advertising everything from leg irons and gang chains to electric shock stun baton and cluster bombs.’ He added: ‘The point is, none of these companies were spotted by any official body tasked with policing the Fair, they were spotted by Amnesty and our partners.’

No DSEI exhibitor has ever been arrested by police or prosecuted by the crown prosecution service (CPS) for illegal activities at the arms fair.

Going back to the April 2016 acquittals of Isa al-Aali and the rest of the eight, these were unfortunately overturned by the high court. This reversal is actually an important development for the story of the Ziegler decision.

*

The Ziegler Four are now bound together in the public mind as a unit.

However, while most of them had worked together quite closely in one way or another, two of them didn’t know each other before this action.

They are from different generations of activism. When they were first acquitted in February 2018, these were their ages: Henrietta Cullinan (56), Chris Cole (54), Jo Frew (38) and Nora Ziegler (28).

*

One of the things that linked the Ziegler Four together was the London Catholic Worker (LCW).

At the time of the action, Nora was living in Guiseppe Conlon House, the LCW building in Harringay, North London. Henrietta’s never lived there, but she was a volunteer at the London Catholic Worker for many years, from 2005 onwards. Jo has been very connected to the Worker, but more as a ‘friend of’ the LCW.

The Catholic Worker movement dates back to 1933, when it was founded by a left-wing Catholic journalist, Dorothy Day, at the urging of a French worker-scholar, Peter Maurin. The basic ideas of the Catholic Worker movement have been described as ‘Christian anarchism’.

The London Catholic Worker is both a house of hospitality for destitute refugees and asylum-seekers and a secure base for nonviolent action for change.

*

Knowing each other through the Catholic Worker, Henrietta, Jo and Nora had taken part in arrestable actions together, including at DSEI 2015 and at Burghfield, the nuclear warhead assembly and maintenance centre in Berkshire.

Jo had known Chris for a while. At the time of the DSEI 2017 action, she had also just started a stint working at Drone Wars UK, a group that campaigns against killer drones, where Chris is the founder and director.

Chris had known Henrietta through the Catholic Worker and other faith-based activism for a long time.

*

What linked all four together was that they were all Christian peace activists who were willing to take arrestable action against DSEI on the ‘No Faith in War’ day of action, 5 September 2017. This was part of a week of action just before DSEI opened.

The 2017 ‘No Faith in War’ day of action included: Islamic noon prayers; ‘Torah Readings’ led by the radical Jewish group, Jewdas; a guided 30-minute ‘Peace Sit’ meditation led by Wake Up London, a group of young Buddhists; as well as Christian prayers and songs from groups such as Pax Christi and the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship.

“I don’t know if I’m a proper anarchist. Or a proper Christian.” - Jo Frew

Like Nora, Jo had become involved in organising ‘No Faith in War’ when it started in 2015. Jo said: ‘I always tried to be involved in the planning, rather than the execution, of the day, because I always knew that, on the day, I would probably be doing something with my affinity group.’

In 2017, one member of Jo’s group, Put Down the Sword, took part in a climbing/ropes action (we’ll hear more about this later), while Jo became one of the Ziegler Four. Other PDTS folk played important support roles on the day for both actions.

*

The original plan for what became the Ziegler action needed eight people to ‘lock-on’ in pairs. A lock-on involves putting your arm into a long reinforced tube and locking your wrist to a bolt or pin in the middle of the tube.

Jo explains that there were supposed to be four large lock-on boxes arranged in a square formation, each holding a post that would stand up. The posts would be linked together to form a tent or ‘tabernacle’, a multi-faith sacred space surrounded by prayer flags.

Nora says that ‘direct action’ is probably not the right description for what they were aiming to do: ‘We knew we wanted to hold the space.’

*

The first thing I asked in each of my interviews with the Four was how they identified in terms of their faith. Most of them struggled with this question in one way or another.

*

I asked Jo if there was a short three- or four-word description she would find acceptable as a description of her faith.

She replied: ‘Not really, because I feel like the things that I want to say that I am, I don’t know if I am them. You have things that you want to live up to, but.... I would want to say “I’m a Christian anarchist” but I don’t know if I am. I don’t know if I’m a proper anarchist. Or a proper Christian. Who knows? Depends who you ask, I guess.’

When I press her, Jo says: ‘I “attend” a Quaker meeting at the moment, but I wouldn’t say I was exclusively a Quaker.’

*

Henrietta tells me she was raised as a Christian in the Church of England, and then she converted to Catholicism after she met her husband and other people who were Catholic.

The minute she experienced the London Catholic Worker, it made sense to her. Making meals for the homeless on a Sunday ‘seemed a lot more meaningful than organised religion’.

Being involved with the Catholic Worker led her to the Big Blockade at Aldermaston in 2010. Henrietta told me how she felt as she lay with other people on the road outside Britain’s Aldermaston nuclear bomb factory in Berkshire: ‘I just felt so happy. There’s a picture of me laying on the ground and I’ve got this big smile on my face so that was kind of how it made me realise that this is a good thing... I included it in my faith, I suppose.’

“It’s funny, when I drive through that area now, I still get really nervous.”

Henrietta also talks about going to Afghanistan in December 2016: ‘just meeting people properly, meeting and sharing daily life with ordinary Afghans, mothers like me and young adults, was a transformational experience.... To meet young people just like the ones that I worked with here in London, and to hear about what they were hoping for, their dreams, and they’re in an environment that is just completely awash with weapons.’

Henrietta describes ‘another important thread – you’re supposed to work for things that are life-giving, that’s part of my faith – choose things that give life’.

*

Nora describes herself as ‘a Christian and an anarchist’. Despite having lived and worked in a Catholic Worker house for five years, and still being involved in it, Nora has never been a Catholic. Her denomination is Methodist: ‘I just ended up going to the Catholic Worker because they were the only other anarchist Christians that I could find.’

Later, talking about the meaning of ‘No Faith in War’ Day, Nora comes back to the question of what she believes: ‘It was, like: “Let’s come together and express together that we believe in God, we believe in love, we believe in peace, and we think that’s incompatible with the arms trade, we think that’s incompatible with borders, with violence, with war.” And even though, a lot of the time, we may have to make compromises to actually achieve real material change, let’s come together and affirm together that we do believe that this is not just words, we do believe that God is a power in the world, even though it is a power that is often not recognised by people, because it’s a gentle and humble power that works through the grassroots. That’s what I believe: it’s a power that works from below, through the grassroots, through solidarity, through people supporting each other. And that is really contrary to the power from above, the powers from above, that oppress, and manipulate, and exploit.’

*

For his part, Chris says: ‘I was brought up a practising Roman Catholic and I’ve considered myself, all my life, to be a practising Christian. I come from the Catholic left, the traditional Catholic left, rather than the establishment-base of Catholicism, and I’ve been involved in religious, and particularly Catholic, peace activism since my 20s.’

He adds: ‘I struggle to be part of the Catholic church at the moment, just because of stuff that’s going on. But I am, doctrinally and by practice, a Catholic.’

In terms of the action itself, Chris points out that it was very much about making a direct link between refugees and the arms trade, and the need to open our borders: ‘we all know that exporting arms helps to create refugees and refugees are fleeing from war zones, so we were focused a little bit on that, but I think the primary focus was the arms fair that was taking place, to disrupt that, and to draw attention to the links.’

*

We’ve come to the night before the action, to a planning meeting at the London Catholic Worker, where, Henrietta remembers: ‘several people had to drop out because of one thing or another, which just left the four of us’.

Chris says, of this meeting: ‘I do remember that we clicked together, as a group. Although we were different ages and genders, there was a lot of trust pretty quickly.’

*

This action had several ‘firsts’ in it.

It was the first time that Chris or Henrietta had ever done a lock-on.

Nora, for her part, had never been (properly) arrested before this action. She had been arrested and then ‘de-arrested’ – released on the scene without being taken to a police station for processing.

*

On the day of the action, Jo can’t remember exactly, but thinks: ‘I would have got up, cycled over to Giuseppe Conlon House at some ungodly hour of the morning. And then, I guess, we put the boxes in the car.’

Nora adds: ‘I think we practised. I think we even practised with the car – as much as we could without neighbours looking at us weirdly.’

Henrietta says: ‘The paint was still a bit wet so we had to put newspaper underneath the boxes’ when they went into the car.

*

When the car got to the right bit of the approach road (going in towards the ExCeL Centre), it stopped, and the four jumped out.

Jo remembers ‘lots of newspaper blowing everywhere’.

Jo says she ‘was really stressed about it, like in a high state of adrenaline’.

Nora was also ‘very, very nervous’, doing the action: ‘It’s funny, when I drive through that area now, I still get really nervous.’

Chris and Jo were locked-on to one box, and Henrietta and Nora were locked-on to the other.

Once they were all locked-on, Chris remembers feeling ‘elated, in a state of euphoria that it had worked’, despite there being so many police officers around: ‘I think, for some reason, we caught them by surprise, really. I don’t know why.’

Chris had been nervous beforehand about getting his hand into the lock-on device quickly enough. When it came to it: ‘I didn’t quite have my hand in [when the police came to him] but there were people around saying: “They’re locked-on, they’re locked-on, don’t pull them.” And the police kind of eased off and that kind of gave me enough time to get actually locked-on!’

According to the police, the four arrived and lay down at 8.54am. Nora was arrested just four minutes later, at 8.58am. Henrietta and Chris followed at 9am, and then Jo was arrested at 9.05am.

So, all four blockaders were arrested within 11 minutes of starting their obstruction of the highway.

*

While they were lying in the road, the four had a lot of ‘support’ from the crowd of anti-DSEI protesters.

Jo: ‘Lots of people come and give you bust cards, and say, “Are you all right?” and “Well done!” and stuff. And that’s nice. But once it’s happened 10 times, you have to say: “No, I really don’t need another bust card.”’

Chris adds: ‘There were lots of people, citizen journalists, sticking a microphone and camera in my face asking: “How do you feel?” [he laughs] “Why are you doing this?” [he laughs some more] After you’ve done that a couple of times, you’ve had enough, you know?’

Nora seems to have found lying in the road peaceful: ‘Maybe that’s just a personal thing for me, I just find the way you just don’t know exactly what’s going to happen, and you have to make split-second decisions, I find that incredibly stressful. The rest is fine. Whatever.’

*

Chris remembers it taking the police quite a while ‘to get the cutters to us’.

Henrietta says: ‘I wrote down at the time that it was a bit like being at the dentist – there’s that vibrating drill which I thought was going to go into my arm.I kind of just zoned out.’

Chris remembers chatting to the police officer cutting into his arm tube: ‘I go through this whole process of wanting to be nice to people and wanting people to like me, so I was chatting to them, and they were fine. We were talking to them about why we were there, and asking them not to do it, and stuff like that.... They were incredibly respectful and making sure we weren’t injured or damaged in any way.’

“It was a bit like being at the dentist – there’s that vibrating drill which I thought was going to go into my arm.”

Jo talks about how sexism, religious bias, racism and classism come into play here: ‘This is the thing about having all kinds of privilege in this situation: being female, being a Christian pacifist, being white, being middle-class and university-educated. The way that police will communicate with me is not bad. I’ve seen at DSEI the difference in the way that people are treated. If I was a man of colour, especially if I was Asian, South Asian, at DSEI, it would be different. I’ve seen police just go for people who’re doing nothing – like one guy, who was a photographer, nothing was happening and he wasn’t doing anything. I guess, because of the “war on terror” they’re on high alert at an event like DSEI. The cutting-out and being arrested is never that terrible for me, but it just shows you how unjust and how racist, how systemically racist, policing is.’

*

Once they’d been cut out of the arm tubes, about 90 minutes after they first lay down on the road, the Four were taken to a police station to be processed.

Henrietta says: ‘I was scared of being in a police cell because other times I’d been very stressed in a police cell. But this time I just went to sleep. So that bit of it was fine.’

“It just shows you how unjust and how racist, how systemically racist, policing is.”

She wrote at the time: ‘Later I found out that, altogether, the #nofaithinwar day had held on for four and a half hours. Altogether, by the end of the week, there were over 100 arrests, some of them just for people standing in the road. I also found out from CAAT that the set-up of the fair was four days behind schedule.’

*

As far as I can make out, none of the Four were interviewed by the police or charged with anything. They were just held in police cells for several hours and then released on bail.

*

When they were released from custody, each of the Four seems to have had slightly different expectations of what would happen next.

Chris thought that it would be dropped, ‘as a lot of these things are’. Henrietta thought they’d be prosecuted, plead ‘not guilty’, and then be convicted and fined. She’d pay the fine, as she had done before, and that would be the end of it.

Jo expected them to end up with ‘conditional discharges’ rather than fines.

A conditional discharge is when you are found guilty, you get a criminal record, but no other action is taken against you – as long as you don’t commit another offence within a certain period of time.

Earlier in the year, in January 2017, Jo had been given a conditional discharge for six months (which had expired by the time of the Ziegler action.)

That was for a ‘No Faith in Trident’ blockade of the Burghfield nuclear warhead factory in Berkshire that Jo had carried out in June 2016 with four other members of Put Down the Sword: Nina Carter-Brown, Nick Cooper, Angela Ditchfield and Alison Parker.

*

Eventually, the Ziegler Four were informed that they were being charged with highway obstruction.

Chris started thinking along the same lines as Henrietta, that they were heading towards a fine.

This was the first time that Nora had been charged with an offence for taking part in a protest, so it was also the first time she’d had to face a trial. She told me: ‘I remember feeling quite bewildered about the whole thing, because I was the least experienced of the activists, and everyone else was really nonchalant about it.... I was quite sort of: “Why is everyone like acting like this is no big deal? This is really stressful and I don’t know what to do.”’

They decided together that Nora would get a lawyer while the other three would represent themselves in court, a common pattern with groups of activists on trial.

Nora went to something like a legal speed-dating event organised by CAAT and met solicitor Raj Chada of Hodge Jones & Allen. He seemed trustworthy, so she asked him to represent her in court.

*

Raj Chada had also been one of the defence lawyers in the April 2016 trial mentioned earlier, where eight protesters who had blocked a road outside DSEI 2015 were acquitted.

In that case, the defence had successfully argued that the blockaders were acting to prevent the illegal sale of torture equipment and weapons sold to countries that abused human rights.

The ‘preventing a crime’ legal argument was broadly accepted by district judge (DJ) Angus Hamilton in April 2016, and he acquitted the eight blockaders.

*

Unfortunately, the prosecution appealed and the acquittals were overturned by the high court in London in July 2017, two months before DSEI 2017.

Among other things, the high court judges found that the crime being prevented (in this case, advertising illegal equipment for sale) had to be ‘imminent and immediate’ for the ‘prevention of crime’ legal defence to be available.

*

So, when the Four met with Raj Chada after DSEI 2017 to talk about the legal arguments they might make in court, he had to break it to them that this ‘prevention of crime’ defence was no longer available.

Raj told me: ‘I’ve done DSEI cases, I think, since 2013, so, a large number of DSEI cases. And we’ve traditionally used “prevention of crime”: that offences were ongoing in the arms fair, or we were trying to prevent crimes against humanity, because they were selling arms to despicable regimes. We actually had some success in those cases. My recollection is, we’ve never lost a DSEI trial – because we kept winning even on those grounds... because we’d got so much evidence about despicable things that happened in the arms fair.’

*

A bit earlier, I mentioned a trial that Jo went through in January 2017 with four others from her affinity group.

At that trial, the Put Down the Sword blockaders asked Reading magistrates’ court to consider their rights under Articles 9, 10 and 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights. These are about the rights to freedom of religion, freedom of expression and freedom of assembly.

Unfortunately, these legal arguments didn’t persuade the court in Reading, and the Put Down the Sword folk were found guilty.

*

Despite this, Raj persuaded the Ziegler Four that the legal arguments in their DSEI case should focus on their rights under the European Convention on Human Rights.

Raj put together a legal defence based on Articles 10 and 11 (freedom of expression and freedom of assembly). Jo, representing herself, also brought in Article 9, saying that her action was an exercise of her religion and should be protected as such.

*

Why did the case end up being called Ziegler, when it’s the last surname of the four, alphabetically?

Chris says: ‘Nora had the solicitor, and, in my experience, they always, if there’s a mix of defended and undefended, they always call it [by the name of the person with the lawyer], so they can just send all the stuff off to the solicitor and it’s usually his or her job to distribute it between the defendants.’

Chris adds: ‘But it also sounds much better as a chant!’ He then whisper-chants: ‘Ziegler! Ziegler!’

*

After several hearings and much delay, the trial finally took place at Stratford magistrates’ court, in front of district judge Angus Hamilton, on 1 – 2 February 2018.

Kirsten Bayes attended the trial as a court support person from CAAT. She says of the judge: ‘Regarding DJ Hamilton, I remember thinking he was being actually quite strict and no-nonsense: he didn’t put up with much from barristers, from either the prosecution or defence. He saw how the law applied and then just applied it, rather than being especially “sympathetic”.’

Raj Chada says of DJ Hamilton: ‘He’s not afraid to go against the grain to whatever he thinks is right. Sometimes that’s helpful to the defence, sometimes it’s not. He is an idiosyncratic judge, in a way, but he gave short shrift to the prosecution in our case.’

*

When I ask Nora what she remembers about the trial, she says: ‘A lot of it was just sitting in really shabby waiting rooms. The amount of support we got was amazing. Just people coming just to show their support, looking after us, bringing food, asking how we were. I remember being really grateful, but also feeling humbled by it.’

Nora says: ‘I remember being really scared of my own statement, and I remember it being really cringey as well. I remember saying something about Martin Luther King and, after, I was just, like: “Oh my God, that’s so cringe”.’ (She laughs at the memory.)

*

When I ask what stands out about the trial, Chris says: ‘If I remember rightly, all of us spoke really well, from the heart, and I think that really communicated. Plus, the prosecution, as usual, weren’t well-briefed, they didn’t know what they were doing.

*

Jo says: ‘DJ Hamilton, as far as I remember, just seemed quite fed up with it all, ’cause I think he’d been given all the DSEI cases. It was just, like: “Well, something’s got to change.”’

*

In terms of the evidence they gave, Henrietta said that she felt her actions were reasonable, given ‘the enormity of the impact of the arms trade.’

Jo says: ‘When I talked about living with asylum-seekers, I actually cried. The prosecuting barrister was a bit, like: “Oh, here’s a tissue.”’

I ask Chris how much work he had to do on his contribution to the trial, given that he’s been on trial many times before for arms trade-related protests.

“If I remember rightly, all of us spoke really well, from the heart, and I think that really communicated.” -Chris Cole

He says: ‘Because I had done it before, it wasn’t completely from scratch. We divided out between us what we would say; we were very careful that the four of us wouldn’t say the same thing, that they would be overlapping rather than all saying the same thing, and that worked quite well, I think.’

Chris told the court about his three decades of challenging ‘the normality and legality of the business of promoting and making financial gain from armed conflict’.

*

The following sections are quite technical, going through the law.

*

Britain ratified the European Convention on Human Rights in 1951.

Article 10 of the Convention says everyone has the right to freedom of expression.

Article 11 says everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and to freedom of association with others.

However, both Articles impose the exact same conditions on these freedoms.

“When I talked about living with asylum-seekers, I actually cried. The prosecuting barrister was a bit, like: ‘Oh, here’s a tissue.’”

One key point here, for the Ziegler case, is that the Convention allows restrictions on freedom of expression and freedom of assembly ‘as are prescribed by law’ to prevent crime.

Another important point is that restrictions on these freedoms are only allowed by the Convention if they are necessary in a democratic society.

*

Section 3 of the UK’s Human Rights Act 1998 says: ‘So far as it is possible to do so, primary legislation and subordinate legislation must be read and given effect in a way which is compatible with the Convention rights.’

*

The Ziegler Four were prosecuted for wilfully obstructing ‘the free passage along a highway’, an offence under the Highways Act 1980.

Whether it’s a pavement or a road, you don’t have to take up the whole width of the highway in order to commit the crime of highway obstruction.

Anything you do that interferes with the ability of someone else to pass and re-pass along the highway counts as a crime... if you don’t have a ‘lawful excuse’.

Various lawful excuses have been recognised over the decades, including the right of a building owner to, say, put scaffolding on the highway (the pavement).

*

This is my understanding of the argument that Raj put forward: if you take Article 10 and 11 Convention rights seriously, then, in the right circumstances, peaceful protest can also be a lawful excuse for deliberately obstructing the highway.

Raj told me that the argument ‘evolved into something much more nuanced’ in its final form at the supreme court.

*

Arguing against this, the prosecution emphasised the words in Articles 10 and 11 allowing restrictions on these freedoms if they are ‘prescribed by law... to prevent crime’.

Henrietta remembers ‘that there was a kind of terrible circular argument that the prosecution seemed to have; you’re allowed to express yourself as long as you’re not committing a criminal act, but, then, if you are committing a criminal act, you’re not allowed to express yourself.... Even the judge said it was a bit circular.’

*

To make legal arguments, you have to provide previous rulings by senior judges and explain how they support the verdict that you are arguing for. Those are legal ‘precedents’ – previous decisions that establish legal principles or rules that you think are relevant to your case.

We will just quote a few sentences from one judgement that DJ Hamilton found relevant: Westminster City Council v Haw, a high court case from October 2002.

Westminster council was trying to get an injunction forbidding the anti-sanctions and anti-war campaigner Brian Haw from having a display of images and slogans in Parliament Square, Central London as part of his unauthorised round-the-clock one-person protest camp.

Mr justice Gray refused to impose an injunction on Brian Haw in 2002. Among other things, the judge recognised that interfering with the right to freedom of expression (Article 10) ‘is permissible where it is necessary – that is, where there is a pressing social need – to do so in order to protect the rights of others.’

However, Mr justice Gray went on: ‘I certainly do not accept that Article 10 is a trump card entitling any political protestor to circumvent regulations relating to planning and the use of highways and the like, but in my judgment the existence of the right to freedom of expression conferred by Article 10 is a significant consideration when assessing the reasonableness of any obstruction to which the protest gives rise.’

He didn’t think that there was ‘any pressing social need to interfere with the display of placards so as to protect the right of others to pass and re-pass.’

Mr justice Gray said that, after taking into consideration ‘the duration, place, purpose and effect of the obstruction, as well as the fact that the defendant is exercising his Convention right,’ he concluded that the obstruction caused by the placard display was ‘not unreasonable’.

This wording suggests that, if there is an unauthorised protest which deliberately causes an obstruction (like Brian’s display), it is not automatically unreasonable and therefore illegal.

The authorities still have to assess ‘the duration, place, purpose and effect of the obstruction’ to judge ‘the reasonableness of any obstruction to which the protest gives rise’.

*

In his judgement on the Ziegler case, DJ Hamilton added to this list. He stressed the importance of: the peacefulness of a protest, whether it directly or indirectly provoked public disorder, how carefully targeted it was, and whether it was connected to ‘a debate on a matter of general concern’ (this phrase comes from a 2007 decision by the European court of human rights).

According to this perspective, the authorities need to work through a checklist of factors when faced with a protest to see whether they should restrict the Convention rights of the protesters.

Is the restriction proportional to the scale of the obstruction that is going on?

*

DJ Hamilton ruled that it was for the prosecution to prove that the obstruction of the highway by the Ziegler Four was unreasonable – and they failed to prove that.

Therefore he dismissed the case against them.

They were acquitted.

‘Not guilty’.

*

Speaking for all of the Four, Henrietta says: ‘We really didn’t think that he would find us “not guilty”.’

The Four had not disputed that they’d locked-on while lying in the road, and that they’d blocked the way for vehicles trying to get to DSEI.

The facts had all been agreed with the prosecution.

The case was about what you thought about the facts; the legal interpretation that you put on them.

*

When she heard that DJ Hamilton had acquitted them, Henrietta says she ‘was just really excited and happy’, saying to herself: ‘Oh, phew, that’s the end of that.’ She adds: ‘Although I wasn’t a teacher, I did get teaching jobs, and I thought it’d be another thing on my record. All of that kind of [worry] went out of the window. I felt a sense of freedom, I suppose.’

*

On the other hand, Nora doesn’t seem to have been that bothered about the verdict: ‘Okay, we got acquitted, that’s nice, but it doesn’t change anything. I don’t care whether a judge thinks my action was right or not because I, obviously, know that [it was right].’

*

Jo, also, wasn’t expecting to be acquitted, and also wasn’t that impressed: ‘I don’t really think the legal system’s that great, so I wouldn’t ever expect it to be any different than “power protecting power”. So, I guess, being found “not guilty”, it’s quite a surprise, because you think: “Oh, maybe the system can’t always protect itself.”’

*

Chris, like Henrietta, was delighted and ‘elated’: ‘I mean, I’ve been found “not guilty” a couple of times before but, you know, this was definitely new.’

For Chris, ‘the most annoying thing was, I was ready with my tweet [to send out on Twitter], and I tweeted “not guily” instead of “not guilty” – that really was annoying!’ (He laughs.)

Here is Chris’s tweet from 10.50am, 7 February 2018: ‘NOT GUILY!!!! Thanks for the support everyone. The work goes on! #StopDSEI #NoFaithInWar.’

*

When Chris heard that the crown prosecution service (CPS) was appealing and the case would go to the high court, he thought: ‘Great! … They’re just gonna shoot themselves in the foot.’

Nora remembers being intrigued by what might happen: ‘Oh, this is interesting. This could be cool if the high court upholds that decision. But, also, there was a danger of them overturning it – which could have consequences for other activists. That’s where it became more, like: “Oh, this action is gonna have consequences more than we initially thought.”

‘But, to be honest, I don’t think I thought about it that much, because at that point it was in the hands of the lawyers, and they were very capable. And I trusted them. And, yeah, we had some amazing lawyers working with us, I mean Blinne and the others. Absolute legends. I think, from that moment, I got more disengaged, in that this is not my fight, this is not my strength. This is what the lawyers are good at. They’ll ask me if they need anything from me.’

Jo was not surprised that the authorities appealed against the acquittal: ‘because, obviously, they go through the rigmarole every two years, when lots of people get arrested at DSEI, and they don’t want anyone to be found “not guilty”.’

*

The Ziegler trial took place at Stratford magistrates’ court on 1 and 2 February 2018.

A week later, on 7 and 8 February, another four DSEI protesters went on trial before DJ Hamilton.

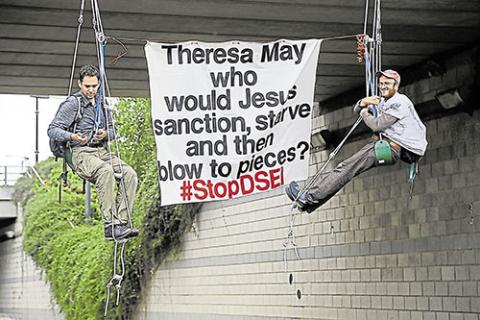

On ‘No Faith in War’ Day, Nicholas Cooper (36), Sam Donaldson (29), Louis Dorton (29) and Tom Franklin (59) had used climbing equipment to hang from ropes fixed to a bridge going over a road leading to DSEI.

DJ Hamilton found them ‘not guilty’ of highway obstruction.

When he applied the tests of ‘reasonableness’ that he’d developed in his Ziegler ruling, the bridge-hangers also qualified as having a Convention rights lawful excuse.

At another DSEI highway obstruction trial that ended at Stratford magistrates a day later, on 9 February, a different magistrate, DJ Jane McIvor, found four protesters ‘not guilty’ using the Ziegler tests.

‘Had they done this on the Strand [a major road in Central London], it would have been pretty unreasonable,’ but, because the action was ‘very targeted and limited’, it was reasonable, the judge was quoted as saying by the Morning Star.

The prosecution dropped charges against the final defendant.

In another DSEI trial of five activists, a few days later, charges were dropped against four of them; the fifth protester was acquitted.

*

There were three Ziegler decisions: ‘Magistrates’ Ziegler’ in 2018, ‘High Court Ziegler’ in 2019, and ‘Supreme Court Ziegler’ in 2021.

In 2018, Magistrates’ Ziegler was proving to be a powerful judgement. If it wasn’t checked, it might turn into a form of legal immunity for highway obstruction at DSEI, a blank cheque for certain kinds of anti-arms trade direct action.

And who knew how far the influence of Magistrates’ Ziegler might spread?

*

As a solicitor, Raj had been able to represent Nora in the trial at the magistrates’ court level; in the high court (and supreme court, eventually), the Four needed barristers to speak in court.

The new additions were three: Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh of Matrix Chambers; and Henry Blaxland QC and Owen Greenhall of Garden Court Chambers.

*

At this point, we have to talk a bit more about the four bridge-hangers.

The CPS also appealed to the high court to ask for a reversal of the acquittals of Nicholas Cooper, Sam Donaldson, Louis Dorton and Tom Franklin. The high court was asked to rule on all eight cases together.

However, the Ziegler Eight turned back into the Ziegler Four because the paperwork for the bridge-hangers had been put in too late.

*

Both the prosecution and the defence team agreed before the high court hearings that DJ Hamilton’s ruling was going to be challenged on the grounds of its ‘unreasonableness’.

Raj Chada, the Ziegler Four solicitor, explained later in a webinar on the Ziegler case that no one, on either side, ‘had prepared for any other type of test’.

Unexpectedly, in Raj’s words: ‘The high court went off on a frolic of its own.’

Without warning, the high court brought in a completely unexpected precedent from family law and allowed the appeal, overturning the acquittals.

*

Here is a crucial section. The judges ruled: ‘In all the circumstances of these cases, we have come to the conclusion that the District Judge did fall into error in a number of respects in his approach to the assessment of proportionality, as we have indicated in going through his individual reasons.’

DJ Hamilton had not struck a ‘fair balance’ between the right to protest and the right of the public to pass along the highway.

*

Henrietta was ‘really disappointed’ by the verdict.

Nora says that she felt ‘not really surprised, but just disappointed’: ‘You know when you’re disappointed that people confirm your bad expectations for them [she laughs] and you’re, like: “Thank you for confirming to me that the justice system is shit.”’

For Nora: ‘it wasn’t our case any more, it was the lawyers’ case, and I trusted that they would represent us, and represent our action, well.’

Nora remembers ‘lots of people coming to support us, standing outside with banners’.

*

I had assumed, before starting work on this article, that the reason that the Ziegler Four appealed to the supreme court was that there was an urgent need to overturn a ruling that would be harmful to other activists.

Raj explained to me that this wasn’t quite correct. The high court’s analysis of the law was so good, Raj says, that he still often uses it in current cases rather than the supreme court judgement.

Raj says that the high court’s attitude to deliberately obstructive protest ‘didn’t really logically, or indeed legally, fit with the rest of the judgement, which says: “You have to look at each set of circumstances in isolation. You need to consider the defendants’ human rights. And then you need to consider the effect of the defendants’ actions on other people, and you balance the two out.”’

Raj told me that after the high court decision, ‘there were large numbers of cases in which this argument was pursued and we still won some of them. We lost more, but we still won some of them.’

He told me about an Extinction Rebellion action at City Airport, during one of the XR rebellions, where the defendant, ‘his bottom had barely touched the road before he was arrested’. Raj was able to use High Court Ziegler ‘because it talked about the length of time’. ‘We said: “Well, look, this cannot be a proportionate interference with the defendant’s right to free speech because he barely had arrived at the demo, and you’d arrested him.” And the magistrates agreed with that. So, there were successes under High Court Ziegler.’

Raj told me: ‘Frankly, within the legal team, there was a great deal of discussion about whether to appeal’ against the high court decision: ‘I, perhaps ironically, was one of the most cautious. We had made significant progress.’

“Frankly, within the legal team, there was a great deal of discussion about whether to appeal. In my view, there was something to lose.”

Before High Court Ziegler, the law was interpreted as saying that the primary purpose of the highway was ‘to pass and re-pass’. That made protest cases really difficult.

Raj explains that ‘High Court Ziegler knocked that out completely’. The High Court Ziegler decision (in paragraph 108) said that there was no primary right for one particular section of the community. Passing and re-passing was just one purpose of the highway. As Raj puts it: ‘You just have to balance all of the rights. That was an incredibly powerful statement. And, again, we used that extensively.’

Raj was concerned that, if they appealed against High Court Ziegler, the supreme court might reinstate the ‘primary purpose’ of the highway as being passing and re-passing.

Raj says: ‘In my view, there was something to lose. I appear regularly in the lower courts, so I’d seen, actually, High Court Ziegler had had some good effects and was working reasonably well. So, I could see that there was something to lose. But, eventually, we all decided that we had to appeal, because of this issue of deliberate obstruction. And the supreme court judgement is so much better.’

*

Chris remembers the discussion that finally led to the decision to appeal to the supreme court: ‘I think all four of us were worried about it going to the supreme court and us losing. Then that would really be a difficult precedent. But Raj was insisting that, because the high court had made this decision, it was already going to be a difficult precedent, so, in a way, we couldn’t lose.’

*

The high court ruling may have been a big step forward, legally, but it was a big step backwards for the Ziegler Four.

The high court said that their acquittal was overturned, they had been convicted of highway obstruction... and they had to go back to Stratford magistrates’ court to be sentenced for their crime.

Jo says: ‘If I’m honest, my main memory is of cycling [to the courthouse] down the River Lea, and cycling back. It was a beautiful sunny day, and I didn’t really care, because it wasn’t a huge sentence.’

Nora says of the sentencing: ‘I remember being really pissed off, that they gave us 12 months’ conditional discharge – which would include the next DSEI. “Really pissed off” is maybe an exaggeration. I was just, like: “Come on!”’

Chris was also annoyed: ‘It really stuck in our craw, you know. We had another date in court and so we turned up to be sentenced. I think we got a conditional discharge for 12 months. Then we had to pay court costs which, for me, it was really galling. I remember it being really unfair. Lots of stuff that I’ve gone through, I don’t know, I haven’t taken it that way, but I found it very unfair, the whole of that day.’

In contrast, Henrietta remembers the sentencing as ‘a friendly occasion’: ‘It was just sort of quite cosy, just the four of us, with Raj, and the magistrate. I just remember that she noticed that none of us earned very much, so she set the fine really low.’

*

By the time the Ziegler case reached the supreme court on 12 January 2021, the UK was 10 months into the COVID-19 pandemic.

The defendants followed the supreme court proceedings through an official online video livestream (not Zoom).

*

Chris was at home: ‘I watched the whole thing and I remember being absolutely convinced after hearing the prosecution side that we didn’t stand a chance and absolutely convinced we’d won after I’d heard the defence case. So, thank God I’ve never been on a jury.’

*

What did the supreme court decide?

The supreme court ‘judgment’ actually has three legal opinions in it. Two make up the majority view that the Ziegler Four should have their acquittal restored to them. A third (dissenting) opinion thought that they should be sent back to the magistrates to be tried again.

All three opinions agreed that, in principle, ‘deliberate physically obstructive conduct by protesters’ can, in certain circumstances, be lawful.

Raj summed up: ‘The key to the judgement was, firstly, it said that the state and, that included the court, had to ensure that a conviction was a proportionate interference with the defendants right to free speech. And what that meant was they had to look at the right to free speech on one hand, and then they had to look at the interference with the rights of others. And they had to balance the two up. And, if they weren’t sure that [conviction] was a proportionate interference, they should acquit.’

*

One of the three Ziegler barristers, Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh, explained the Ziegler decision in a webinar held by her legal firm, Matrix Chambers, in September 2021. The whole of Blinne’s talk is well worth watching; we’ll just pick out three points.

*

Firstly, Blinne picked out a line from lady Arden’s opinion in the ruling: ‘The Human Rights Act 1998 has had a substantial effect on public order offences and made it important not to approach them with any preconception as to what is or is not lawful.’

Lady Arden’s ruling here isn’t just about highway obstruction, or even just obstruction. She is talking about all public order offences, a very important development.

*

Blinne pointed out that the supreme court said that arrest, prosecution, conviction and sentencing are all restrictions on the Convention rights of protesters.

So, a police officer on the scene of a protest might reasonably think they’re justified in arresting a protester but, later, when more facts are available, it might not be justified to prosecute them or, if prosecuted, convict them.

At each level, the decision-maker must make a fresh assessment of the facts available to them, in relation to ‘proportionality’, before deciding to restrict the Convention rights of the protester.

*

Deciding whether a particular restriction on a protest was proportional or not was defined by the supreme court as a ‘fact-specific enquiry’.

In crown court, where more serious cases are heard, it is the jury who decides on the facts.

Putting the jury in charge of this proportionality decision, Blinne said ‘is capable of being game-changing in criminal trials.’

*

Let’s go back to the second point. The supreme court put a burden of responsibility, in terms of protecting protesters’ Convention rights, not just on judges and juries and prosecutors, but also on police officers.

Raj explains: ‘It means the arresting officer has to assess whether or not their action – ie the arrest – is a proportionate interference [with someone’s Convention rights].

‘So, they would have to assess: “Look, here’s somebody protesting. I’m about to interfere with their right to free speech. Is that a good and proper exercise of my discretion? Or is there another way to deal with it?”

‘Really, what it comes down to is that it places greater emphasis on the police to consider alternatives. So, is there an alternative? For example, you give the protesters a warning: “Look, we’ll let you protest for a couple of hours, but then, thereafter, you must move.”

‘So, there’s greater weight placed on the police to at least consider alternatives. And consider what the effect of an arrest would be. I think that that is quite profound.’

*

‘After the supreme court decision,’ Raj told me, ‘the CPS [crown prosecution service] dropped a large number of cases.’

Kirsten Bayes, the local outreach co-ordinator for the Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT), says: ‘Regarding impact, Ziegler has pretty much come up in all the protest-related cases I have supported since the judgement. It has become something of a measuring stick for what makes a direct action protest “reasonable” from the perspective of the law, and sets limits on how the police can respond. I am not a lawyer but, for me, this case was another small piece of freedom for the ordinary citizen to resist oppression, that was carefully and painstakingly won from the state.’

*

One XR climate activist who benefited from Ziegler is Amelia Halls, a member of XR Youth, who was 23 when she had a conviction overturned.

Ams was one of 50 XR rebels arrested at a protest at London City Airport in October 2019. She was convicted of highway obstruction in April 2021 (she got a six-month conditional discharge and £400 in court costs).

Ams says that she decided to appeal against her conviction partly ‘as a continued tactic of civil disobedience to continue pushing the courts, to continue taking up the court’s time’.

The evening before her hearing, her solicitor got an email from the court: ‘it said something about not challenging the appeal, but it didn’t say Ziegler in it.’ The supreme court had made its Ziegler decision about six weeks earlier.

In court the next day, the prosecution said they were not challenging the appeal, so the appeal was successful. Ams’s conviction was overturned. She says: ‘I was really thrilled, really delighted. That had been my first conviction and to get it overturned was amazing. To know that it was the Ziegler ruling that meant it was overturned was really great because it showed that these rulings and this pushing the courts to make these sorts of decisions works. We are on the right side of history and these rulings are showing that.’

Ams was the third XR protester to have their conviction overturned. Before her were Emma-Rose Goodwin (then 47) on 3 August 2021 and Robert MacQueen (then 65) on 4 August, the day before Ams.

*

Raj describes Ziegler as ‘a landmark judgement, a seminal judgement’ which has had a profound effect on cases after it: ‘But what’s also happened is that there’s been a fight-back. The prosecution and the state have sought to try to limit it – and will be seeking, no doubt, to try to reverse it at some point.’

In April, the attorney general, Suella Braverman, referred the Colston Four acquittal to the court of appeal, in order to try to restrict the uses of Ziegler.

If successful, the appeal would not overturn any Colston acquittals, but it would stop other protesters charged with criminal damage from calling on the Ziegler principles in their legal defence, in the future.

*

So far, though, a lot of people have benefited from Ziegler.

Henrietta says: ‘Oh, it’s fantastic, I’m just really, really glad. I almost don’t dare find out: will that keep going? Or: how does it work?’

Chris says: ‘It’s great that people don’t have to go through all the court case crap. Most people don’t see all that crap and all the post-conviction stuff, you know, fines and prison. Prison is hard, it really has an impact on people.’

Jo says: ‘I’m really glad that we said to the lawyers, “Okay”, without really understanding the full significance of it. Well, I didn’t, anyway, maybe the others did. I’m particularly pleased that it might be a little bit of a counter to the new Policing Act, which we didn’t foresee at the time, obviously.’

*

When she first heard about the supreme court ruling Henrietta was thrilled.

Jo says she doesn’t really remember the ruling coming out: ‘I was probably dealing with some sort of crisis in our house, because I live with people who are dealing with the home office, which is destroying their lives.

Chris was ‘elated’.

Nora says she ‘was full of doubts’ when she heard the decision: what if the government decided to crack down more on protest, ‘which will affect other people more than it will affect me – that will affect people of colour, poor people, transgender people?... I simultaneously felt happy and also thought: “Oh, shit, I hope this doesn’t have bad consequences for someone else.”

*

I ask Raj how Ziegler fits with his work, his life, his career. How does it fit in with what he’s done?

Raj replies, simply: ‘It’s made me hugely more busy.’ And he laughs.

Raj goes on: ‘I’m incredibly proud of it in a way, and proud of, not so much the judgement, but actually of the four defendants. I think it’s amazing. They took a stand against a disgraceful arms fair. And they’ve ended up in the supreme court, and they’ve made legal history. And they’ve created an entirely new movement for activists in the legal field. And often that’s not really the lawyers, because we can just write something. But it’s the defendants that have to put up with us and, you know, great credit to them for persevering throughout it all, and for undertaking the action, and then keeping fighting, because it is a bit of a drain at times.’

*

When I was interviewing Nora, I left one question right to the end. I said: ‘This case is called Ziegler... how do you feel about that?’

Nora said: ‘Well, it’s unfortunate. In Germany, “Ziegler” is a fairly common name, but here it’s really not common at all, which means that it’s very easy to google me. I find it’s just a bit unfortunate because it means it’s definitely not something I can hide from.’

In the Matrix Chambers webinar, Raj said that district judge Hamilton calls the Ziegler decision ‘the Hamilton judgment’.

I ask Nora what she thinks of that.

She says: ‘I mean, Ziegler just sounds better.’

Register here now for this Zoom event: https://tinyurl.com/ZieglerOneYearOn-PeaceNews