In 1969, the Nixon administration charged eight US activists with having conspired to cross state lines ‘with the intent to incite, organize, promote, encourage, participate in, and carry on a riot’ outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Infamously, the judge (Julius Hoffman) ordered the only Black defendant (Bobby Seale) to be bound and gagged, after he insisted on his right to represent himself.

Seale’s case was declared a mistrial but five of the remaining defendants received sentences of five years.

Declassified FBI documents later revealed that the judge had been colluding with the FBI and the prosecution throughout the trial.

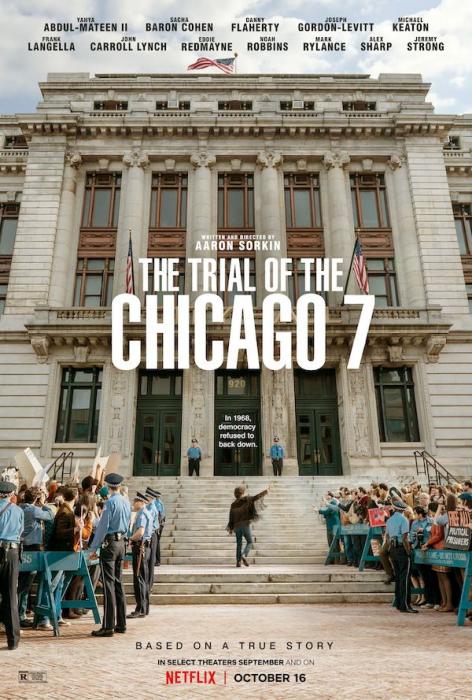

In his new film, The Trial of the Chicago 7 (which received its Netflix release on 16 October), Aaron Sorkin has managed to fashion a reasonably diverting two hours from this material, while also taking many liberties with the historical record. Unfortunately, some of these do a serious disservice to those involved.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the case of pacifist Dave Dellinger, one of the defendants. A courageous and principled nonviolent revolutionary who turned his back on a privileged upbringing to spend several years in prison as a conscientious objector during the Second World War (where he took part in hunger strikes to desegregate the US prison system), Dellinger was deeply involved in both the civil rights and peace movements and was co-editor of the radical magazine, Liberation.

Yet Sorkin portrays Dellinger as naïve Boy Scout troop leader who, in a climatic scene, punches out one of the court marshals.

In reality, Dellinger repeatedly intervened – both verbally and physically, but always nonviolently – to defend Seale, who later recalled that: ‘Dave was a true revolutionary humanist… the main Chicago co-defendant to support my … [constitutional] rights’.

In an insightful review of the film for Waging Nonviolence, Robert Levering – who was a young antiwar organiser in Chicago at the time – argues that Sorkin’s film is important because it exposes ‘an unjust and racist legal system’ while ‘vindicat[ing] those who protested a senseless and immoral war’.

While there’s certainly something to this, there is also something fundamentally flawed about a film that frames the Vietnam war almost entirely in terms of its impact on US soldiers.

Not only is the impact of America’s invasion of Vietnam on the Vietnamese barely mentioned (one brief reference to napalm in the opening frames was so fleeting that I’d forgotten it by the end of the film) but Sorkin even airbrushes them out of the film’s final scene.

In the film, one of the defendants (Rennie Davis) has been keeping a list of ‘Americans who have been killed since the day we were arrested’ so as not ‘to forget who this is about’. Given the opportunity to make a ‘brief’ statement prior to sentencing, Hayden chooses to read the list, sending the judge into meltdown.

In reality, it was Dellinger who read the names of the dead from both sides in court.

This treatment of Vietnamese deaths is no small matter. And, whether it reflects Sorkin’s politics or not, it clearly serves the cause of the US empire.

It’s been estimated that over 1.5 million Vietnamese were killed during the conflict that the Vietnamese call, with good reason, ‘The American War’. The US death toll was roughly 58,000.

Someone who ignores the Vietnamese who died, while sanctifying the memory of the US war dead, is less likely to care about the massive expansion of drone warfare (no US deaths) or question the militarist assumptions underlying president-elect Joe Biden’s frequent call for God to ‘protect our troops’.

It would have been both easy and natural to have incorporated Vietnamese deaths into the film.

The My Lai massacre – in which GIs killed roughly 500 unarmed villagers – finally became public knowledge during the trial. And the defendants attempted to introduce information about it into the proceedings – the judge ruled it irrelevant.

But unlike the FBI’s assassination of Black Panther Fred Hampton (which also took place during the trial), My Lai is never mentioned.

‘Though exceptional in its scale,’ notes historian Christian Appy ‘the My Lai massacre reflected the patterns and psychology of brutalisation that were at the heart of American military operations in South Vietnam.’

This, I suspect, is the real reason for its absence.

It’s just too revealing.