My work as coordinator of the Network for Police Monitoring (Netpol) has kept me busy for some months now supporting the rights of Extinction Rebellion (XR) campaigners to exercise their freedom of assembly.

XR activists have been out on the streets since 7 October and over 1,400 have been arrested so far. Now the police have abandoned any pretence at facilitating their rights and have imposed a blanket ban on XR protests covering the whole of London.

As well as publicising incidents of excessive policing tactics — the basis for a report on this month’s protests that Netpol published on 20 November — much of this work is unseen and unglamorous.

It has involved giving advice and support to XR’s own legal team and to organisations coordinating legal observers, as well as briefing journalists on the powers the police are using.

It has also involved warning about and preparing for a far more aggressive response from the police than we saw when climate activists took to the streets back in April.

On a personal level, it has also meant answering dozens of calls at odd hours from XR activists, often on release from police stations, who are unclear about their rights, have no solicitor and who are worried about what happens to them next. It has been a privilege to help.

Possible common ground

One of Netpol’s core aims when we started back in 2009, however, was to try to highlight and educate campaigners about the everyday experiences of policing, particularly in working-class and racialised communities* up and down the country.

What might seem like the worst case of police violence to a first-time environmental campaigner is commonplace to millions of people in the UK.

For 10 years, we have sought to encourage a greater understanding among protesters and community organisers about why oppressive policing, the misuse of police powers and what often seems like barely concealed contempt from individual officers for us as citizens are issues in which we can and should find common ground and shared solidarity.

This is why, for me, supporting Extinction Rebellion in a spirit of co-operation and friendship over the first week of its protests has, at times, been extraordinarily difficult – particularly due to its invariably tin-eared insensibility about the nature of policing and the state.

Deaths in custody

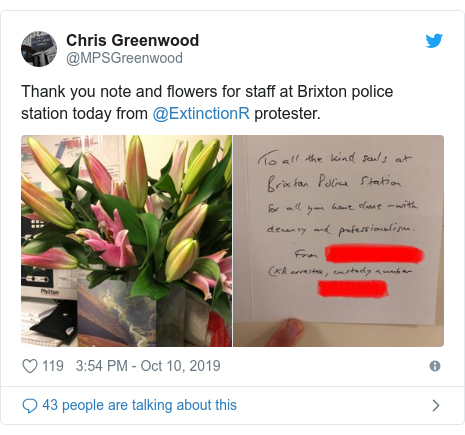

The hardest point eventually came on 10 October, when the Metropolitan police’s head of media, the former Daily Mail crime reporter Chris Greenwood, tweeted about a thank-you note and flowers left by an XR arrestee for staff at Brixton police station.

This is a building where Wayne Douglas, Ricky Bishop and Sean Rigg, all young black men, died in custody.

“I cannot remember the last time I was quite so angry at members of a movement whose rights I seek to help defend.”

It is a place I repeatedly stood outside protesting as an active member of the Newham Monitoring Project over nearly three decades, because of violent policing towards south London’s black communities.

As I said at the time the photo was shared, spending a decade as the secretary of the United Families and Friends Campaign, the coalition of relatives who have lost loved ones at the hands of the state, has meant I’ve attended more deaths in custody funerals than friends ‘ weddings.

Lack of empathy

This was all unbelievably horrible, but seeing comments defending police officers currently at Brixton as having nothing to do with these deaths, one XR supporter saying she ‘didn’t see how skin tone fits into this story’, and another asking ‘Do we have to be tribal about everything?’, was entirely worse.

I cannot remember the last time I was quite so angry at members of a movement whose rights I seek to help defend.

The complete lack of understanding or empathy for communities who experience racist policing, coupled with the outright, blatant racism – make no mistake, choosing to not ‘see’ race and erasing its historic importance to relations between the police and racialised peoples is unquestionably racist – does seem to suggest we have moved practically nowhere in trying to find the shared solidarity that was so important to setting up Netpol in the first place.

Of course, this is just one moment, amidst a wave of protests by thousands of people.

The organisation I work for does not criticise the tactics of the groups we work with, focusing our energies instead on the misconduct of the police. It is easy, too, to discount moments like this as minor compared to the frightening scale of the climate emergency facing the planet.

However, something about this particularly depressing moment has stuck with me and I have been unable to shake it.

Perhaps it is because the question of whether Extinction Rebellion has a ‘race problem’ is already the subject of national media debate, or perhaps because its year-zero rejection of almost all campaigning that preceded it as the product of failure always risked a detached indifference to the experiences of others.

Perhaps it is because this contrasts so sharply with the often exaggerated efforts to express such deep sympathy for officers who are making arrests.

Micro-aggressions

Reflecting further over the weekend on how Extinction Rebellion’s often thoughtless messaging is perceived from the outside, I realised I have finally started to properly understand, as a middle-aged white campaigner against racism and police brutality for almost 30 years, what young black activists mean by ‘micro-aggressions’.

This is the term used for those small, but persistently hurtful, discriminatory slights and insults, both intentional and unintentional, towards society’s marginalised or racialised groups.

It is a relatively new concept for me, but it is exactly what a dog-whistle call for arresting more black people instead of ‘non-violent protesters’ means.**

This is what leaving flowers at a police station in the heart of the black community means.

This is what dismissing concerns about these slights and insults as a distraction from the bigger picture means.

And, frankly, if someone who has been campaigning for as long as I have can learn something new from a bunch of flowers left at a police station, then so can Extinction Rebellion.