Why make reportage drawings? Graphic artist Olivier Kugler was commissioned by Médecins Sans Frontières (‘Doctors Without Borders’) to travel to Iraq, Kos and Calais to interview Syrian refugees. He took photographs and used translators to record stories. So why not stop at that?

Why make reportage drawings? Graphic artist Olivier Kugler was commissioned by Médecins Sans Frontières (‘Doctors Without Borders’) to travel to Iraq, Kos and Calais to interview Syrian refugees. He took photographs and used translators to record stories. So why not stop at that?

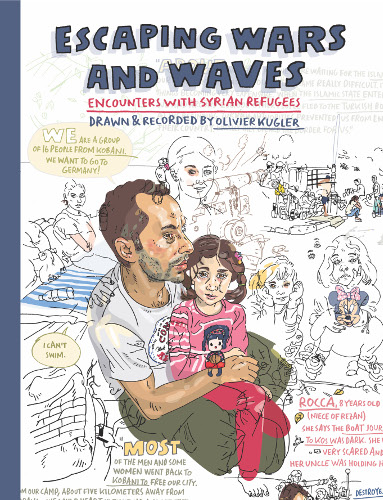

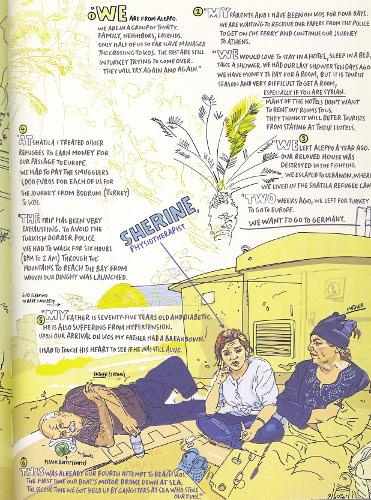

On first viewing, I didn’t like the drawings in this book. I shrank back from lines that didn’t please me, from flat Photoshop washes. But I was curious because something interesting happens in these illustrations. They are complex; they operate as a vehicle to record many dimensions: the speech of the Syrians is hand-lettered across the pages, we are led from one thought to another by linking arrows that bind the visual pictures to the aural experiences of listening.

The sections of the book follow the route of refugees into Europe ending pertinently and powerfully with Syrian families finding hospitality in the German village of the artist’s birth.

The drawings of people and places are fragmented and layered; the movements of hands, feet and posture overlap as the narrators move through their stories, shifting and stuttering in tandem with their journeys across borders. Often the pages are interviews with groups, such as Wisam and Hadya’s family in Birmingham. Or young men in a shack in Calais.

The scripts are finely edited with interjections that create conversations backwards and forwards across the image. Sometimes we follow one person’s story such as Djwan who runs a business in Domiz camp just inside Iraqi Kurdistan, providing a music sound system and plastic chairs for weddings. There are details in the pictures – the tea bag, the tobacco pouch – that are annotated, specifically named and noted.

“Here is a 21st-century form that is working for us: it catches, it hooks and we look.”

So again, why create drawn reportage? The more I looked, the more I realised that something was happening similar to Swiss modernist artist Paul Klee’s ‘taking a line for a walk’. The eye slows down and is enticed along the lines of faces and feet. It is encouraged to make a journey through the pictures. The presence of hand-written words slows us down and roots us in the page, the picture, the story. This is the functional importance of the drawing as a transmitter of bad news. Where the eye may glide over a photograph, may groan at a block of text, here is a 21st-century form that is working for us: it catches, it hooks and we look.

The nineteenth century had its artist-journalists who travelled to war zones of the world to draw the news: a scene, a picture, an emotion, posted back to the Illustrated London News or the New York Times. Olivier Kugler is part of our century’s movement of journalists, like Joe Sacco, who use the 20th-century language of comics to document the world. Sacco takes us into Goražde by including himself in the drawings. Kugler does it through enmeshing our imagination in the timelapse of lines and visible voices.