For all its horrors, the coronavirus pandemic has created a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for a shift to a more equitable, socially just, climate-resilient and zero-carbon world – if we can grasp it. But to do this, we need to co-create and share inspiring and visionary ideas of what that better world might look like and how we might get there. In words of Raymond Williams, ‘to make hope possible, rather than despair convincing’.

PN approached activists and campaigners from across the UK to find out what book, film or play inspired them with its visionary ideas. Here’s what they told us ..

VIRGINIA MOFFATT:

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula Le Guin (Ace Books, 1969)

An icy world on the far corners of the galaxy inhabited by a genderless people. And an alien visitor attempting to persuade them to join the interplanetary clear bloc they don’t believe exists.

These are the elements that make up The Left Hand of Darkness, a story of mistrust, betrayal, love, and learning to understand and embrace the other. This 51-year-old sci-fi classic still resonates today, as the characters experience pain,despair, joy and hope. For ‘Light is the left hand of darkness, and darkness the right hand of light.’

Inspired and beautiful, it will stay with you.

Virginia Moffatt is an author and activist who lives in Oxford.

RAKESH PRASHARA:

I will never see the world again by Ahmet Altan (Granta Books, 2019)

Ahmet Altan is a journalist and author from Turkey currently serving life sentence without parole there after he was convicted of sending ‘subliminal messages’ to the planners of the failed coup of 2016.

This book is a story about resilience and imagination in the face of injustice and cruelty, which we need in our movements now more than ever as we move into a time when action is needed to avert the climate emergency and to find solutions for the social injustices that continue to cause harm to the most vulnerable.

Rakesh Prashara is the deputy chair and membership officer of the Greens of Colour, a Green Party liberation group.

CLAIRE POYNER:

Star Trek (NBC, Paramount, CBS, Amazon Prime Video, 1966–)

Even with The Original Series, Star Trek aimed to offer a positive view of humanity in the future. Creator Gene Roddenberry intended to show a ‘wagon train to the stars’ with a multi-racial cast which also featured a woman in a position of authority (almost). Or at least as far as one could get away with in the 1960s. It also featured a Russian on the bridge in the midst of the Cold War and a Japanese man just 20 years after the Second World War. Oh, and did I mention that the woman was also Black?

So, yes, the programme meant a lot to people who were used to not seeing people like them on TV, not unless they were portraying a servant, a baddie, a Second World War soldier, or a victim of some sort.

A mainstream TV series showing a future where humans are ‘no longer obsessed with the accumulation of things’ and who have ‘eliminated hunger, want, the need for possessions’. How radical is that!

Claire Poyner is the administrator for Peace News, Network for Peace and Christian CND.

DAVID MACKENZIE:

The Horses by Edwin Muir (1956)

Muir’s poem is post-apocalyptic in theme and we are still hoping and working for the avoidance of End Times and to halt the continuing spin down into dystopia. And yet the power of these words does not rest solely in the poet’s wonderful skill but in a very special evocation: the conviction that humanity’s alienation from the rest of nature is readily curable, that the recovery of a sense of embedded connection is the key to our future, and that the future can be wholesome and utterly beautiful.

David Mackenzie is a retired schoolteacher and a grandparent who does stuff for peace and other precious things.

GABRIEL CARLYLE:

Antarctica by Kim Stanley Robinson (Harper Collins, 1997)

Kim Stanley Robinson has mastered the art of writing utopian fiction that isn’t just a manifesto re-jigged as a guided tour or that other cliché, the paradise disrupted by an outsider.

This comic eco-thriller set in the near future starts with a hijacking and ends (almost) with its eclectic cast of characters crafting a series of proposals for a New Antarctic Treaty foregrounding peace, sustainability and social justice.

Along the way it takes in the history and geology of the world’s coldest continent (the first human only set foot on the continent proper in 1895), co-operatives, blimps, a wild ride to an under-ice heated lake, political intrigues in Washington and a love story. And what is true in Antarctica may just turn out to be true everywhere else as well.…

Gabriel Carlyle is the PN reviews editor.

TONY TELFORD:

Kindness by Naomi Shihab Nye (1995)

A manifesto in 34 lines.

The title might lead you to expect something warm and fuzzy, but this is a poem rooted in the real world.

Nye counsels us to find our path, not in her luminous words, but in our own experience: ‘Before you know what kindness really is,’ she writes, ‘you must lose things’. You must travel in that ‘desolate landscape... between the regions of kindness’.

More specifically, ‘Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside, you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing’. Because then ‘it is only kindness that makes sense any more’.Tony Telford is a cartoonist and writer who lives in Cardiff.

BRIAN LARKIN:

The Long Loneliness by Dorothy Day (Harper & Brothers, 1952)

I’m inspired by the life of Dorothy Day because she became the change she wanted to see in the world.

During the Depression, Dorothy started the Catholic Worker newspaper. For decades, at great cost, it articulated a Christian pacifist stand. In contrast to the Catholic church in the US at the time, she put gospel teachings into practice, founding houses of hospitality where community members welcomed the homeless, fed the hungry and themselves lived in poverty.

Dorothy denounced the ‘filthy rotten system’ and was arrested numerous times – notably for resisting preparations for nuclear war by publicly refusing to take part in compulsory air raid drills.

Brian Larkin is co-ordinator of the Edinburgh Peace & Justice Centre. His latest charge is aggravated trespass for an XR Peace blockade of BAE Systems.

ESME NEEDHAM:

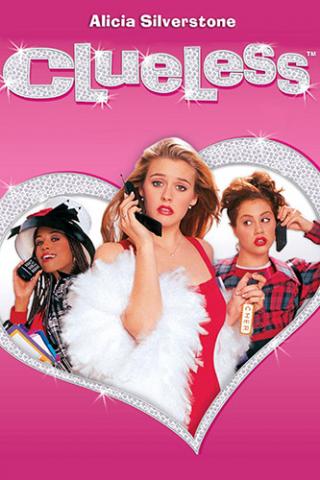

Clueless (Paramount Pictures, (1995)

‘I needed to find sanctuary in a place where I could gather my thoughts and regain my strength,’ muses Cher, the protagonist of Amy Heckerling’s adaptation of Austen’s Emma. She’s talking about the shopping mall, but this film isn’t as vacuous as it appears.

While Cher is imperfect and occasionally complicates other people’s lives, instead of being relegated to the role of ‘vapid rich girl’ she is allowed to be herself without judgement from others or from the film itself.

She is a funny, kind young woman who takes pride in her purple clogs – surely an inspiration to us all.

Esme Needham is a young feminist active in the Divest East Sussex campaign.

DAVID POLDEN:

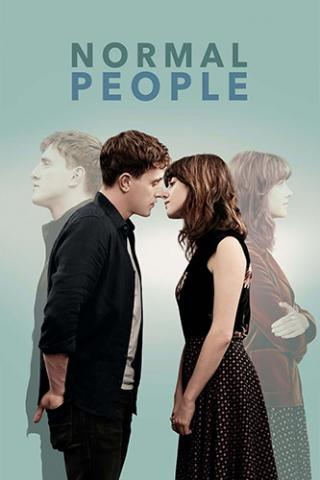

Normal People (Element Pictures & Screen Ireland, 2020)

This life-affirming series follows a young Irish couple who begin a sexual/love relationship while still at school in Sligo – a relationship that they later return to after both moving to Dublin as students at Trinity College.

For me, their evident joy in their relationship and bravery and good sense in dealing with the many obstacles that they face – both in themselves and from other people – shows that a better world is possible.

David Polden is a long-time peace activist and a news editor for Peace News.

MARTIN SCHWEIGER:

Medical Care in Developing Countries: a symposium from Makere edited by Maurice King. (Oxford University Press, 1966)

It may seem strange to recommend an old medical textbook but this book has already changed the world for the better. It provides the shared experience from so many health workers coping with adverse circumstances.

Practical procedures are explained in straightforward language enabling inexperienced practitioners to make real differences and save lives.

It was the first textbook I encountered that set out the basis for providing health care. Twelve axioms of medical care are given, the first of which is: ‘The medical care of the common man [and woman] is immensely worthwhile.’

Martin Schweiger trained as a doctor, has worked in public health and is now involved in the Menwith Hill Accountability Campaign.