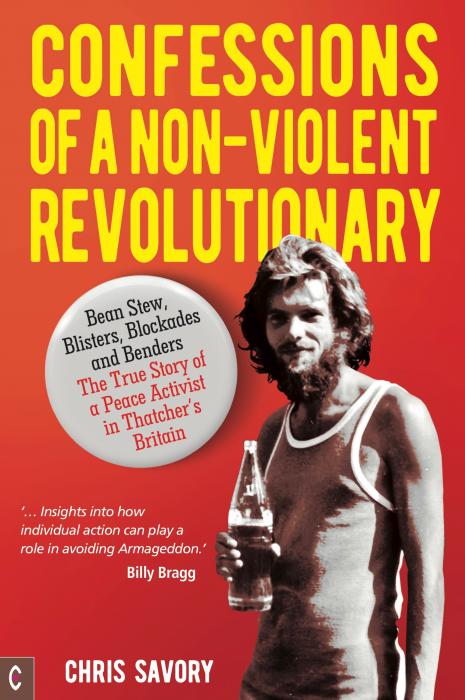

In the summer of 1981, the young Chris Savory left his place studying economics at Oxford University to join the peace movement and the UK’s counterculture. His recently-published memoir of this time, Confessions of a Non-Violent Revolutionary, is by turns moving and humorous. This extract takes up the story in 1982:

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, most disarmament-related civil disobedience was in the form of sit-down protests in central London.

The focus had now shifted to military bases and other significant places involved in the preparation for nuclear war.

This strategy had the advantage of allowing local groups all over the country to find suitable targets for action in their own areas, highlighting the huge US military presence in our country and publicising spy-bases, bomb factories, weapons storage facilities, nuclear bunkers and other civil defence installations – as well as airbases.

The disadvantage was that most of these places were deep in the countryside and protests were not seen by many ordinary citizens.…

The first Yorkshire-wide NVDA [non-violent direct action] was initiated by a group from Leeds CND. They suggested a mass trespass at Easingwold in North Yorkshire.

This was the site of the bunker that North Yorkshire county council would operate from in an emergency and it was also a college for training staff from around the country in civil defence.

We took a mini-bus and a couple of cars from Bradford and were around 80-strong altogether at the protest.

In the event we were able to walk straight into the site and hold a tea party outside the locked front doors.

Group consensus prevented a few hotheads from trying to break into the buildings and, after a couple of hours of being observed by a lone security patrol, we left and went home.

A local radio reporter turned up and I was able to put our message across on BBC Radio Yorkshire. Non-violent revolution was proving duller and more difficult than I had imagined back in St Joseph [a town in Kansas where he’d worked in early 1982]....

The last night of 1982, this tumultuous and extraordinary year for me, was not spent boozing and partying and singing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ but freezing my butt off in the Oxfordshire countryside.

I had come down from Bradford to visit family and friends in Oxford over the festive season, but being a peace activist was a full-time occupation, and so I had made sure that there were some actions I could take part in too.

“Nonviolent revolution was proving duller and more difficult than I had imagined.”

The main event was a blockade of USAF Upper Heyford [a US air force base in Oxfordshire]. New Year’s Eve was chosen for the symbolism of starting the New Year as we intended to go on: working for peace and nuclear disarmament.

USAF Upper Heyford was one of the biggest and most important American airbases in Britain and it was home to a squadron of long-range bombers, with significant nuclear capacity. The plan had been to create a human chain round the entire airbase and in doing so block all the entrances and exits.…

Blockading Heyford

We arrived at Upper Heyford in a minibus from Oxford at around six in the evening. It was already very dark, and the cloudless night sky sparkled with stars that warned of a seriously cold night.

With good local knowledge, our group from Oxford had chosen to block a country lane that was the only route to a rear entrance of the base.

Our driver had taken a circuitous route in order to put the police off our actual intentions, and the plan was to get out of the bus quickly and double back on ourselves to block the road before the cops had cottoned on to our destination.

The driver turned left at a crossroads and then stopped suddenly. We exited as fast as possible but were slowed down by the bulk of our clothing and boots.

Finally, we were out, and we started half-running, half-walking back to where we wanted to block the road. A group of four or five coppers saw what we were doing and moved to intercept us.

It was like a grown-up game of British Bulldog. The police couldn’t cover the whole width of the lane, so they targeted individuals, letting others slip past.

I was close to the verge on the left of the lane, and a burly sergeant, red-faced and wheezing, shoulder-barged me. I fell awkwardly into the two-foot deep ditch by the side of the road. I was unhurt, but shocked at being assaulted by a member of the constabulary.

The police soon gave up, though, as most of our group had got past them, and they had clearly been briefed not to make unnecessary arrests.

I got up and scurried down the road to join the group. This was the first and only time that I was assaulted by the police. I could easily have hurt myself badly as I fell. My youth and fitness and my many layers of clothes no doubt helped prevent any damage.

This activity had got the adrenaline flowing, and for about an hour we were high on the success of evading capture and successfully blocking the road.

However, we began to realise that no traffic was trying to get past us. A messenger was despatched to find other groups and bring back news.

It transpired that, in order to avoid conflict, the commander of the base had decided to close it for the night once everyone was in or out after seven o’clock. There had been more activity at the main gate for an hour, but not enough protestors to effectively block the gate which had a significant police presence to clear the way for vehicles.

We now had to stick it out until after midnight on our own.

We kept our spirits up by singing peace songs and received a welcome hot drink from a support car.

From 10 o’clock onwards, we were getting very cold as the thermometer plunged to well below freezing.

After midnight, we walked a couple of miles to the pre-arranged pick-up point and were delighted to see our minibus approaching.

Piling in, we started to thaw out, and convinced ourselves that it had been a worthwhile exercise. A small success, and the best thing was that, after we got dropped off at Oxford station to walk back down the Botley Road to our friends and fellow eco-activists Jon and Jenny’s house, a newsagent had left an Oxford Mail poster outside: ‘Peace Protesters close Heyford Base’ it read.

Not entirely true, but a great souvenir.

Greenham

We woke up on New Year’s Day 1983 with the news that around 40 to 50 women had broken into Greenham Common whilst we were at Upper Heyford and had managed to get onto a silo.

A picture of them dancing on top of this stark symbol of war made headline news and became an iconic symbol of our struggle. They were arrested and a special court session was convened in Newbury for New Year’s Day for them to face charges.

Jon took us down in his VW camper and we hung around outside the courthouse for a couple of hours. The crowds grew steadily, and we must have numbered over 200 when the women started emerging.

Wildly whooping, cheering and hugging, we sang the Greenham anthem, over and over again with pride: ‘You can’t kill the spirit, she is like a mountain, old and strong, she goes on and on and on’

Our movement was growing stronger by the day. CND membership was exploding upwards and opinion polls showed small majorities in favour of ‘Refusing Cruise’ (missiles).

More importantly for me, CND was officially embracing Non-Violent Direct Action (NVDA) as a legitimate tactic and a string of large-scale actions were planned for this New Year.