It must have been a strange sight: the ex-suffragette leading a procession of soldiers marching four abreast down Whitehall, under the banner ‘Lift the Hunger Blockade!’

It must have been a strange sight: the ex-suffragette leading a procession of soldiers marching four abreast down Whitehall, under the banner ‘Lift the Hunger Blockade!’

The Women’s International League (WIL) had been demonstrating in Trafalgar Square on 6 April 1919 against the continuing blockade of Germany and Austria-Hungary. WIL was the British section of an international peace group, the International Committee of Women for Permament Peace (ICWPP), which had been established at the 1915 Women’s International Congress at the Hague.

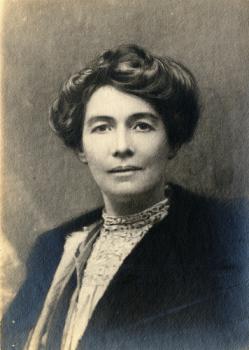

Beforehand, a daily newspaper had called upon soldiers to attend the event to break it up, and they turned up in force. However, the paper had failed to reckon with the persuasive powers of the speakers, including the veteran feminist and anti-war campaigner Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence (pictured left).

A resolution to end the blockade was passed with enthusiasm by the 10,000-strong crowd who demanded to know what would be done with it. ‘I will take it to Downing Street if the army will come with me,’ Pethick-Lawrence replied, and they agreed to join her.

‘Until the Germans learn a few things’

In place since 1914, Britain’s illegal naval blockade of Germany had ‘sought to starve the whole population – men, women and children, old and young – into submission’ (Churchill). It may have been responsible for as many as 750,000 deaths during the war.

After the armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, the blockade was maintained strictly until March 1919 and then more leniently until July, leading to perhaps a quarter of a million additional civilian deaths. British officials took the view that they didn’t want to relax the blockade ‘until the Germans learn a few things’.

ENDNOTES

[1] Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, My Part in a Changing World, Gollancz, 1938, p325.

[2] Pethick-Lawrence, op. cit. Because she failed to submit the leaflet distributed at the 6 April demo – which featured a photograph of severely emaciated Austrian children – to the censor, WIL’s new national secretary, Barbara Ayrton Gould, had to appear in court and was unable to attend the May 1919 Women’s International Congress in Zurich. Anne Wiltsher, Most Dangerous Women, Pandora, 1985, pp204 – 205; Katherine Storr, Excluded from the Record: Women, Refugees, and Relief, 1914-1929, Peter Lang, 2009, p244. A second activist was also prosecuted: Eglantyne Jebb – who had co-founded the Fight the Famine Council on 1 January 1919, and who would go on to launch the Save the Children Fund in May 1919 – (ibid.; Jill Liddington, The Long Road to Greenham, Virago, 1989, p135 – 136). Wiltsher writes (incorrectly) that, as a result of the 6 April demo, ‘WIL had managed to collect one million rubber teats to send to German mothers unable to nurse their babies because of their own malnutrition’ (Wiltsher, op. cit., p205) – she appears to have the chronology confused here. See Storr, op. cit., p243.

[3] Liddington, op. cit., p136; Pethick-Lawrence, op. cit.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Stephen Shalom, Imperial Alibis, Southend Press, 1993, p119.

[6] Nicholson Baker, Human Smoke: The Beginning of World War II, the End of Civilisation, Simon and Schuster, 2008, p2, citing Churchill’s post-war book The World Crisis.

[7] C Paul Vincent, The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany, 1915 – 1919, Ohio University Press, 1985, p141. This figure – which excludes deaths from the 1918 flu pandemic, the total of which was undoubtedly boosted by the blockade – was calculated by the German National Health Office at the close of the war. Drawing attention to the ‘peculiar’ manner in which this figure was calculated, Vincent writes that, while it may be too high, ‘there is no question that the vast increase in civilian mortality after 1914 was largely attributable to the blockade’ (ibid., p145). The death rate of children between the ages of one and five rose by 50 percent during the war, with rickets becoming ‘commonplace’ among the survivors (ibid., pp137, 139, 146).

[8] David Stevenson, 1914 – 1918: The History of the First World War, Penguin, 2005, p512.

[9] Shalom, op. cit.