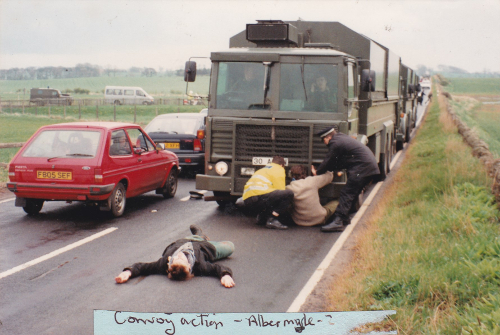

When people discover that the huge trucks they’ve just seen on the road have nuclear bombs in them, they are often shocked and outraged. Not just because the convoys are a potential danger but often people are politically opposed to nuclear weapons, which are suddenly made very real when a convoy overtakes on the motorway or passes by their front door. In Scotland, where Trident was high on the agenda during the independence referendum campaign, the number of members of the public reporting sightings to Nukewatch has increased.

It became clear from social media comments, which ranged from ‘these trucks pose no danger whatsoever’ to ‘the end of the world is nigh’, that many people really have no knowledge of the real potential for an accident involving the convoys or its possible consequences or where to find solid information.

In Scotland, we saw an opportunity to circumvent the Westminster/ministry of defence (MoD) smokescreen. David Mackenzie and I investigated the little known Civil Contingencies Act 2004 (Contingency Planning) (Scotland). The act links the warhead convoys to the responsibilities of Scottish local authorities and the Scottish government for community safety – without as usual blaming it all on Westminster.

Obviously the UK’s nuclear policy and the whole Trident system including transport is determined by the UK government but dealing with the consequences of an accident sits within the Holyrood remit.

Using devolution

For many campaigners in Scotland our experience of our devolved government is vastly different to what we’ve experienced with Westminster. When I walk into Holyrood [the Scottish parliament – ed], I feel that it’s mine. We use parliamentary rooms for meetings, liaise with members of the Scottish parliament (MSPs) and generally feel we are entitled to be there. There is no big glass screen between the public gallery and the chamber. As someone who generally identifies as an anarchist, I surprise myself by all this.

Our collaboration with Mark Ruskell, a Scottish Green MSP who has robust campaigning credentials, seemed very natural. Mark’s office was able to get answers from Scottish local authorities about their risk assessments and communications with the public, when we might have been ignored.

When the MoD released their first set of guidelines to local authorities in the ‘80s, some councils were very upfront in explaining that they would not be able to protect the health of the public in the event of a serious radiation release and in calling for an end to the convoys. We hoped that the Scottish government would take a similar position.

However our initial approaches to minister Paul Wheelhouse only produced disappointing responses telling us that it was all fine and they would cope. Then the Scottish Greens used one of their rare hour-long ‘members’ debates’ to initiate a discussion in the parliamentary chamber on the findings in our Unready Scotland report. As he is on the Nukewatch phone tree and has been out filming the trucks, Mark Ruskell was able to introduce the debate by talking from personal experience about convoys passing him and his children.

Many other MSPs, including some from the governing Scottish National Party (SNP), backed our call for a review. At the end of the debate, Annabelle Ewing, minister for communities and legal affairs, announced that she was going to ask the police and fire services to review their arrangements to reassure ‘all of us’ (which seemed to include herself). This was a step forward and we continue to push for that process to be made transparent.

Investigative journalist Rob Edwards has exposed the fact that after a convoy exercise in 2011 the MoD regulator required the MoD to urgently review its emergency ‘public protection zones’, but this has still not been done. Midlothian council has passed a motion agreeing to question the MoD about safeguarding the public and we hope other councils follow.

Hopefully a survey of English councils will be undertaken before long. Meanwhile Nukewatch continues to track convoys and to use that information with all the tools that are available to us; political lobbying, public education and nonviolent direct action to expose this particular element of the UK’s nuclear weapons system.

------------------------------------------------

Unready Scotland A summary of the report

by Jane Tallents

Nuclear warheads are regularly transported on public roads to and from the atomic weapon factory at Burghfield, in Berkshire in England, and Coulport on Loch Long, in Argyll and Bute in Scotland. At the royal naval armaments depot (RNAD) in Coulport, the warheads are stored and loaded on Trident submarines. Since these warhead convoys carry nuclear materials along with high explosives, this unique transport poses serious questions about public safety.

In the autumn of 2016, MSP Mark Ruskell conducted a survey of local authorities on routes taken by the warhead convoys. Based mainly on the results of that research, Unready Scotland scrutinises the preparedness of Scottish civil authorities to deal with any incident or accident involving the convoys that transport nuclear weapons.

In Scotland, the Civil Contingencies Act (2004) governs the responses of local authorities (and other ‘Category 1 Responders’) to threats to public safety. The act requires Category 1 Responders to conduct a risk assessment of potential threats and to keep the public informed.

None of the councils surveyed (those through which nuclear warheads are transported) conduct risk assessments of nuclear weapon convoys on their roads. Some councils claim to rely on generic assessments conducted by their local Resilience Partnership. None of the councils surveyed inform their public about the nuclear warhead traffic. There is also no evidence that the Scottish government has taken any active step to ensure compliance with the act.

Unready Scotland also examines the complex challenges the civil authorities would face in the event of a serious incident of the kind rehearsed in ‘Exercise Senator’, an official roleplay last run in 2011. ‘Unready Scotland’ concludes that there is no evidence that Scottish civil authorities would be able to cope with a nuclear warhead incident.

The MoD make it clear that their prime concern would be to secure the weapons themselves, while the Category 1 Responders would have to manage accurate and prompt public information (including countering false stories spreading fast on social media), complex evacuations in highly-populated areas, as well as making arrangements for people to take shelter in their own homes. This would all be on a scale that has not been tested in practice. The evidence that has been gathered makes it impossible to accept bland assurances that all is in hand.

The report points out the need to take account of the changing environment affecting the convoys, such as the rapid growth in social media communication and the recently adopted Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. It points out that while military matters are reserved to the Westminster parliament in London, community safety is wholly devolved to the Scottish parliament in Holyrood. The report concludes by recommending that the Scottish government carries out an honest and open review of the preparedness of the Scottish civil authorities.