Why exactly was there a Cuban Missile Crisis 60 years ago?

When the US signed an agreement in 1959 to put Jupiter nuclear missiles into a non-nuclear weapon state neighbouring the Soviet Union, there wasn’t a ‘Turkish Missile Crisis’.

From their Turkish base, the Jupiters could easily reach Moscow – and deliver warheads 100 times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima.

Despite this provocation, the USSR didn’t start a military confrontation with US forces.

In contrast, in October 1962, when the CIA discovered that Soviet medium-range nuclear missiles had been placed in Cuba, the US declared an international crisis, raised its nuclear forces alert level to DEFCON 2 (just short of actual nuclear war) and began a naval blockade of Cuba, forcibly stopping Soviet ships and submarines.

Five days after US president John F Kennedy made a television speech announcing the presence of the missiles in Cuba, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev proposed a solution to the crisis: you withdraw your missiles from Turkey and we will withdraw ours from Cuba.

As Serhii Plokhy points out in Nuclear Folly: A New History of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy (also known as ‘JFK’) was enthusiastic about the swap idea at first. (He had been leaning in favour of airstrikes on the Cuban missile sites.)

JFK told his top advisors on 27 October: ‘In the first place, we last year tried to get the [Jupiter] missiles out of there because they’re not militarily useful, number one. Number two, it’s going to – to any [woman or] man at the United Nations or any other rational [woman or] man, it will look like a very fair trade.’

After some internal debate, the US ended up publicly rejecting the Cuba-Turkey swap. History has forgotten about the Jupiters. US propaganda requires us to believe, in Noam Chomsky’s words, that the US is Good, and what it does is Good. Therefore, the stationing of massive US nuclear weapons on the border of the Soviet Union by definition could not have been a threat to peace, while the USSR doing the same thing in Cuba must have been an appalling and destabilising threat to peace.

I should point out that JFK did privately agree to the Cuba-Turkey trade in a secret message to Khrushchev. The US also publicly sort of promised, with lots of qualifications, not to attack Cuba in the future. That was the basis for the USSR agreeing to withdraw its missiles.

National security?

Why was the US so dead set against Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba?

It wasn’t because they were a danger to the US homeland.

In the evening of 16 October, in a top-level crisis meeting just after the CIA had confirmed the existence of the Soviet missiles, both JFK and his defence secretary, Robert McNamara, said that the missiles didn’t matter in military terms. Kennedy said: ‘They have got enough to blow us up anyway’.

Earlier in the meeting, Kennedy and his advisors had spelled out some of their real reasons for taking such a strong stand.

McGeorge Bundy, the US national security advisor, pointed out that if Soviet missiles were allowed to remain in Cuba, they would deter any US military attack on the island: ‘If this thing goes on, an attack on Cuba becomes general war. And that’s really the question....’

The president’s brother, Robert F Kennedy (‘RFK’) was also in the crisis meeting – as the attorney general and as one of the president’s closest advisors.

RFK followed on from Bundy, saying: ‘Of course, the other problem is in South America a year from now. And the fact that you’ve got these things in the hands of Cubans here, and then, say, some problem arises in Venezuela. And you’ve got Castro saying: “You move troops down into that part of Venezuela; we’re going to fire these missiles.” I think that’s the difficulty....’

A third problem was identified by JFK and by a state department official, Edwin Martin. The president said, of the Soviet missile force: ‘It makes them look like they’re coequal with us.’ Martin added: ‘... it’s a psychological factor that we have sat back and let them do it to us. That is more important than the direct threat.’

To sum up and translate these concerns: (1) Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba would deter the US from attacking Cuba. (2) They might also deter US military intervention elsewhere in South America. (3) They would also reduce the world’s fear of US violence and that might give more countries the courage to defy US wishes.

These were the real reasons the Cuban Missile Crisis happened.

We know what was said in these meetings because president Kennedy made secret recordings of almost all the top-level White House meetings during the crisis – and the tapes have been declassified.

There are over 650 pages of transcripts from these meetings in a gripping book, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis (Harvard University Press, 1997). The transcripts (also available online) give a terrifying view of the twists and turns of US decision-making during the 13 days of the first part of the crisis.

After the disintegration of the Soviet Union, researchers began to gain access to Soviet archives, leading to, among other studies, ‘One Hell of a Gamble’: Khrushchev, Castro, Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1958 – 1964 (John Murray, 1997).

This was written by Russian historian Aleksandr Fursenko and Canadian-American historian Timothy Naftali after they were allowed access to the archives of the top body in the Soviet system, the politburo (known in 1962 as the ‘presidium’) as well as the archives of the GRU military intelligence agency and several Soviet ministries.

Serhii Plokhy’s Nuclear Folly covers US and Soviet policymaking, as you’d expect, and adds a much-needed Cuban dimension. Conflict between the USSR and Cuba, extending into November, threatened to put the world back on the edge of disaster, as Plokhy skilfully explains.

Plokhy, a historian at Harvard university in the US, has put together a very readable, extremely informative and eye-opening one-volume history of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Financial Times rightly described Nuclear Folly as ‘arguably the most authoritative and cleverly written work on the subject yet produced.’

At the same time, Nuclear Folly is a mainstream Western book written by a mainstream Western historian. This means that some crucial facts and perspectives about the crisis are either left out or barely mentioned.

So, for example, Plokhy refers to the 6.30pm White House meeting on 16 October that the quotes above came from, but he doesn’t include these quotes. Plokhy provides a whole page of material from this meeting, including JFK saying: ‘They have got enough to blow us up anyway’.

However, Plokhy does not refer, on this page or anywhere else in Nuclear Folly, to the material quoted above on the deterrent effect of Soviet missiles in Cuba or on the JFK-Martin ‘psychological factor’.

This is not a side issue. This goes to the heart of why the crisis happened at all.

There may be some room for interpretation in terms of what these comments mean and how important they are in understanding US foreign policy in 1962, but it is hard to see how you are doing your job as a historian if you cut these top-level conversations completely out of the story.

US terrorism

Similarly, while he does discuss it quite a bit, I think Plokhy should have included more information on the US campaign of terrorism against Cuba. Authorised by president Dwight D Eisenhower, the programme was renamed ‘Operation Mongoose’ by the Kennedy administration in November 1961 and overseen by Robert Kennedy.

We should note that US military action came on top of crushing economic sanctions that took a heavy toll on the people of the island, with ‘severe health effects’ according to the American Association for World Health. The association’s 1997 report, Denial of Food and Medicine: The Impact of the U.S. Embargo on Health & Nutrition in Cuba, concluded that: ‘A humanitarian catastrophe has been averted only because the Cuban government has maintained a high level of budgetary support for a health care system designed to deliver primary and preventive health care to all of its citizens.’

The US campaign against Cuba is most famous for its failed Bay of Pigs assault in April 1961. Over 1,000 right-wing Cuban exiles who had been armed, trained and organised by the CIA landed on a beach in the Bay of Pigs on the south side of the island, attempting to overthrow the government. They were rapidly defeated by the Cuban military.

The invasion preparations had been set in motion under Eisenhower but the final stages were overseen by JFK, who made key decisions about the operation and who gave the green light for it to go ahead.

That may be the only US-sponsored terrorism against Cuba that most people know about – apart from the plots to assassinate Fidel Castro – but there were hundreds of US-sponsored attacks over the decades.

The stationing of US nuclear weapons in Turkey, on the border of the Soviet Union, by definition could not have been a threat to peace.

Luis Posada Carriles, who took part in the Bay of Pigs attack and who was a paid CIA agent in the mid-1960s, went on to become what some have called ‘the Osama bin Laden of Latin America’.

Among his many other crimes, Posada carried out the first in-air bombing of a civilian airliner in South America on 6 October 1976. Cubana Airline Flight 455, flying from Barbados to Cuba via Jamaica was carrying 73 passengers and crew, who were all killed by the two explosions on board. Declassified documents show that the CIA had advance notice that Posada was planning to attack a Cuban airliner.

In his most brazen move, Posada boasted to a New York Times reporter, Anne Louise Bardach, in June 1998 that he had organised a series of 11 bombings in Cuba the previous year, at hotels and restaurants. The attacks killed one person, an Italian tourist named Fabio di Celmo, and injured 11 others.

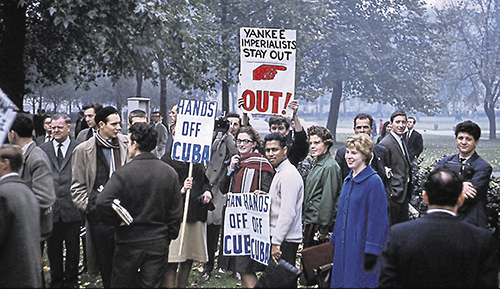

Getting back to the Missile Crisis, here is a list of US-sponsored attacks carried out in mid-1962, compiled by Noam Chomsky: ‘Also in August, terrorist attacks were intensified, including speedboat strafing attacks on a Cuban seaside hotel “where Soviet military technicians were known to congregate, killing a score of Russians and Cubans”; attacks on British and Cuban cargo ships; the contamination of sugar shipments; and other atrocities and sabotage, mostly carried out by Cuban exile organizations permitted to operate freely in Florida.’

This paragraph in Chomsky’s Hegemony or Survival draws on the writings of US historian Thomas G Paterson (Kennedy’s Quest for Victory, Oxford University Press, 1989) and former CIA analyst and former US ambassador Raymond Garthoff (Reflections on the Cuban Missile Crisis, Brookings Institution, 1987).

I don’t think any of these attacks are mentioned in Nuclear Folly.

If, in August 1962, the KGB had organised strafing attacks on a Turkish hotel where US military technicians were known to congregate, killing 20 or so US and Turkish people, I think Plokhy would have mentioned this, even if the US government had reacted as calmly and quietly as the Soviet government did in real life.

There is one particular US-sponsored terror attack in 1962 that Plokhy should definitely have mentioned.

On 8 November 1962, right-wing Cuban exiles armed, trained and organised by the CIA bombed a Cuban factory and killed 400 workers, according to the Cuban government. This bombing is also discussed by Garthoff in his Reflections on the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Garthoff comments: ‘the Soviets could only see [the 8 November attack] as an effort to backpedal on what was, for them, the key question remaining: American assurances not to attack Cuba’. This means that the terror attack was dangerous for the entire world, as it threatened the superpower deal that ended the first phase of the Missile Crisis.

Plokhy emphasises, quite rightly, that November was a very dangerous month, as there were still Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba, and there was serious friction between the Cuban and Soviet governments over what happened to them.

Plokhy gives a terrific description of the diplomatic mission carried out by top Soviet leader Anastas Mikoyan, ‘the only Presidium member who had objected to the deployment of nuclear arms on Cuba and who tried to stop the nuclear-armed Soviet submarines from coming to the island’. Khrushchev sent Mikoyan was sent to Havana to keep the Cubans on board while removing the nuclear weapons they thought were necessary to stop the US invading, and satisfying US demands for verification of the withdrawal.

Plokhy gives space to report on a Soviet private, Veselovsky, firing at a Cuban military patrol on 7 November while drunk (no one was injured), but he does not mention the CIA-sponsored factory bombing that killed 400 Cubans the day after, which must have had a significant impact on the Mikoyan-Castro negotiations.

Worm’s-eye

There is a lot to admire about Nuclear Folly; this has been a critical review. One aspect of Nuclear Folly that must command praise is the fresh material Plokhy has uncovered and organised that brings out the human dimension of the crisis.

Drawing on previously-untapped KGB files in Ukraine, on memoirs and other Soviet documents, Plokhy has put together a detailed, human, ordinary Russian soldier’s-eye view of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

For example, when the first six R-12 nuclear missiles landed at Casilda harbour on the south coast of Cuba on 9 September 1962, the accompanying Soviet soldiers found that they had a mighty job ahead of them just getting the missiles and their launchers to the base area over 100 miles away on the north side of the island.

Colonel Ivan Sidorov’s 637th missile regiment had to build new roads – and reinforce bridges.

It was difficult to get the transporters (carrying 72-foot missiles) along Cuban country roads. It was even more difficult to get them through the narrow, often winding streets of Cuban towns.

In the town of Caunao, Sidorov’s men found they needed to take a sharp right turn into a very steep (30°) slope. It looked as though they would have to demolish a three-story local council building as well as a statue of Yuri Gagarin, the Soviet cosmonaut.

Eventually, the regiment found another way. They took their missiles through Caunao but in a different direction, then circled back and re-entered the town on another road. This enabled them to take the right exit out of town without knocking over Gagarin’s statue or smashing into the council offices.

Stories such as these bring the crisis to life. I won’t quickly forget the descriptions of the sweltering heat below decks on the journey to Cuba. The hundreds of soldiers on each Soviet ship were not allowed up on deck into the fresh air in case they were spotted by NATO spyplanes. They spent weeks lying in their bunks in temperatures that sometimes went above 50 °C.

--------------------------

“That’d be goddamn dangerous”

Meeting on the Cuban Missile Crisis in the White House, 6.30pm on 16 October 1962.

President John F Kennedy: ‘Why does he [Khrushchev] put these in there [Cuba], though?’

National security advisor, McGeorge Bundy: ‘Soviet-controlled nuclear warheads?’

Kennedy: ‘That’s right. But what is the advantage of that? It’s just as if we suddenly began to put a major number of MRBMs in Turkey. Now that’d be goddamn dangerous, I would think.’

Bundy: ‘Well, we did, Mr president.’

Kennedy: ‘Yeah, but that was five years ago.’

[Actually, 15 US Jupiter medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) were sent to Turkey during Kennedy’s presidency, in 1961 or 1962. The agreement with Turkey had been announced by the previous president, Dwight D Eisenhower, in October 1959.]

Deputy under secretary of state for political affairs, U Alexis Johnson: ‘We did it. We did it in England.’

[The agreement to put US Thor intermediate-range ballistic missiles into the UK was reached in 1957. The 60 Thors (range 1,500 miles) arrived in 1958. 59 of the missiles were made ready to launch during the Cuban Missile Crisis.]

Declassified audio and transcript: www.tinyurl.com/peacenews3676