, photo Josh White, courtesy Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community,Los Angeles.jpg)

Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft may seem an unlikely place to host an exhibition of 1960s Warhol-inspired socially-engaged prints from California, but these brightly-coloured, life-affirming texts by Corita Kent make for an exciting dialogue with artworks by members of the Roman Catholic local artistic community in the permanent collection.

In 1921, sculptor and type-designer Eric Gill was one of the founders of the Roman Catholic Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic on Ditchling Common; many artists and craftsworkers joined.

The museum’s primary focus is on the work of members of the guild, but recently it has been celebrating the work of ground-breaking women designers and artists whose work, beliefs and politics have affiliations with the guild.

Corita Kent (1918–1986) became a nun at 18. In 1941, she graduated with a BA in Fine Art from Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles, California. Between 1938 and 1968, she lived and taught in the Immaculate Heart Community, becoming chair of the college art department in 1964.

Corita’s classes at the college were an avant-garde hotbed with teaching by prominent, artists, designers and inventors, such as Alfred Hitchcock, John Cage, Saul Bass, Buckminster Fuller and Charles and Ray Eames.

Ditchling Museum is screening short films of her classes showing her to be an inspirational teacher as a well as a remarkable artist.

The exhibition concentrates on her output between 1952 and 1972 when her work was becoming increasingly political. In 1951, she gained an MA in Art History and began using screenprinting to create striking and affordable art.

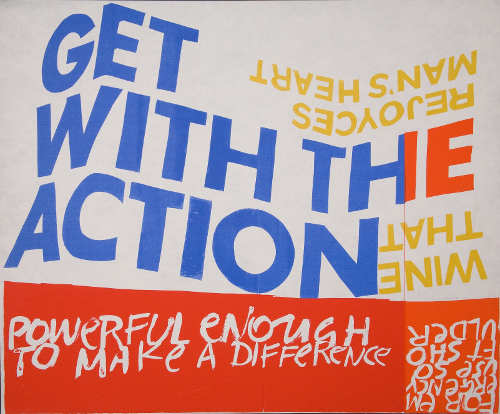

By the early 1960s, inspired by the work of Ben Shahn, she started to work with words alone. Corita saw letters as formal objects and valued them for their looks, but her use of text and abstract coloured shapes provide an intellectual message beyond the immediate appeal of the word.

Like Warhol, many of Corita’s images were taken from advertising and she combined these with texts from priests, rabbis and poets. Her work is undeniably religious, but she also understands the impact of commerce, and uses this to celebrate her faith by making prints which are powerful and joyful.

In one piece, she compares Jesus’ mother Mary to a tomato (a slang term for a luscious young woman), and in another she combines the packaging of Wonderbread with a quote about hunger from Gandhi.

Corita gained attention as an artist during the period of Vatican II (1962–65) when the Roman Catholic church began to modernise. Around this time, the radical priests Daniel Berrigan and his brother Philip played an important role in awakening Corita’s social conscience and directing her attention to the pressing social issues of the time, including the Vietnam War and racial inequality in the US.

Responding to this call Corita said: ‘I couldn’t march and be in the public that way. [Instead] I had to bring into the work… The idea that using words with visual forms and using short passages is often a way to help awaken people to something they may not be aware of, rather than enclosing it in a book or making a speech.’

In the turbulent year of 1968, in response to escalating accusations from elders within the church that her work was blasphemous, Corita chose to return to secular life. She continued to work for social justice for the rest of her life, producing works for the American Civil Liberties Union and Amnesty International, as well as working for IBM and the US postal service.