At the National Eisteddfod main literature awards, two Druids partly unsheathe a sword above the winning author’s head and ask the audience: ‘A oes Heddwch?’ (‘Is there peace?’) ‘Heddwch!’ (‘Peace!’) the audience shouts in return. Only when this ritual has been performed three times can the author sit in the bardic chair. So is Wales a peace-loving nation? What does our history and heritage tell us, and how are people working for peace today?

The centenary of the First World War has brought a heightened awareness in Wales of the loss and waste of that war, creating an opportunity to question the ‘logic’ of war and celebrate those opposing it.

‘Wales for Peace’, a Heritage Lottery-funded project based in the Welsh Centre for International Affairs (WCIA) in the Temple of Peace in Cardiff, is doing just that. The question at the heart of this project is: ‘In the 100 years since the First World War, how has Wales contributed to the search for peace?’

Engaging with community groups and schools, the project has researched ‘hidden histories’ of individuals and groups to share them through public exhibitions and talks, creative events and projects in schools, and online. Various strands have emerged, including objection then and now, the role of women, international solidarity, refugees and asylum seekers and the voice of young people. Particularly in schools, project activities aim to support young people in thinking critically about the past, exploring its relevance to our situation today, and asking what we can do to bring about change.

One thing has emerged: Wales does have a peace heritage, traced back at least as far as active involvement in the ‘Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace’ (founded in 1816), and to ‘the Apostle of Peace’, Merthyr Tydfil MP Henry Richard, who worked tirelessly to establish the principle of arbitration into international law.

After the First World War, there was a spate of activity in the 1920s and ‘30s. MP and philanthropist lord David Davies founded the department of international politics in Aberystwyth, sponsored the building of the Temple of Peace and Health in Cardiff, and was instrumental in the work of the Welsh League of Nations. Having fought in the trenches, Davies was passionate about establishing a strong international order to maintain peace. His sisters, Gwendoline and Margaret, were influential in founding the Welsh education advisory committee (1922–1939) to ‘advance the teaching of peace and the principles of the League of Nations in schools throughout Wales’.

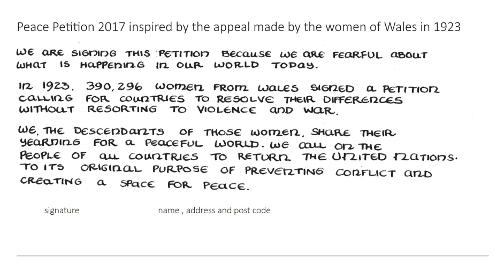

Action was, however, not limited to the rich and powerful. In 1922, Welsh Baptist minister and pacifist Gwilym Davies, sent the first ‘Message of Peace and Goodwill’ from the children of Wales to the children of the world, an act repeated annually on 18 May ever since. Two years later, 60 percent of the women in Wales (390,296 of them) signed a petition addressed to the women of America, asking them to persuade their government to become a full member of the League of Nations, thus safeguarding peace for future generations.

Later examples of Wales’ peace heritage include welcoming Basque refugee children during the Spanish Civil War, Welsh participation in the anti-apartheid movement and the march of the Welsh group ‘Women for Life on Earth’ from Cardiff to Greenham Common in 1981 – a movement that initiated the Greenham Common women’s peace camp.

What inspires all this activity? Particularly in the early 20th century, religion was a prime motivating factor. The influence of nonconformist chapels with their strong pacifist tradition was instrumental. Aled Eirug’s research on Welsh First World War conscientious objectors found their motivation to be religious conviction or membership of the International Labour Party and belief in the brotherhood of man.

While Cymdeithas y Cymod (the Fellowship of Reconciliation in Wales), whose core members belong to churches and chapels, is still active, other factors may favour and motivate peace initiatives. Wales is a small country where people tend to know one another, so activities are easier to manage. There is a sense of community and an understanding of what it means to live alongside a more powerful neighbour and to cherish a culture that is different and in jeopardy, thus fostering empathy for underprivileged or displaced others.

Peace now

However, the peace movement in Wales faces serious challenges. According to the Wales Peace Institute Initiative, 85 percent of the total area of Wales is designated by the ministry of defence as a ‘low flying area’. All Welsh local authorities have signed up to the UK government’s ‘armed forces covenant’ and 74 percent of Wales’ state secondary schools were visited by the army in 2011–2012. Military training areas are dotted across Wales and a large area of the west coast is used to test remotely-piloted drones for military purposes – an issue actively highlighted by direct action taken by members of Cymdeithas a Cymod.

The commemoration of the First World War has given the peace movement a springboard from which to create a lasting legacy, particularly focusing on peace education. Mid-Wales Quakers are actively involved in delivering peace education activities in a number of primary schools with 14 schools joined up to the Wales Peace Schools scheme and a Young Peacemakers’ forum being formed.

Another legacy will hopefully be the establishment of a Peace Institute in Wales, with a remit to produce high-quality research and to promote positive practice on issues relating to peace, human rights and well-being.

The 1924 women’s petition is currently being replicated, as explained by Awel Irene: ‘Without Facebook or television to help, this was an amazing achievement. The women were concerned about the state of the world and they wanted peace. After all the suffering of the Great War, they wanted to see the League of Nations contributing towards a world without war. Their efforts have inspired “Heddwch Nain/Mam-gu” (“The peace our grandmothers wanted”), a project that will take their descendants into 2024. A new petition mirroring the aspirations of the 1920s is being circulated throughout Wales and its aim is to reach people of all genders and in countries worldwide.’

Yes, there is an ongoing need to be vigilant, but there are also grounds for optimism. ‘A oes Heddwch?’ ‘Heddwch!’