The Russian Revolution of 1917 would not have succeeded without fearless nonviolent action by hundreds of thousands of civilians and soldiers. Even the ‘storming’ of the Winter Palace on 25 October was largely nonviolent. Yes, there was plenty of revolutionary armed action in Russia in the course of 1917, but there were also many extraordinary, inspiring, surprising moments that can and should be celebrated by nonviolent revolutionaries.

Rebel herstory

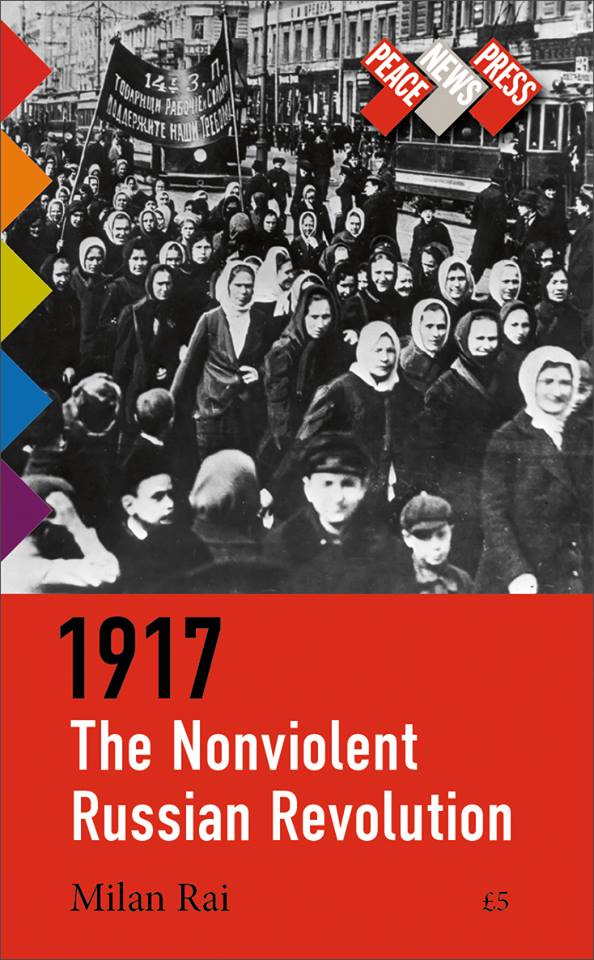

As many people know, the Russian Revolution took place in two parts. The February revolution began on International Women’s Day, 23 February (Russia was on a different calendar then). Thousands of women textile workers and housewives took to the streets of Petrograd, the Russian capital, to protest at bread shortages. (Petrograd is today known as St Petersburg, as it used to be before 1914.) Workers at the huge Putilov works had been locked out by the owners the day before, and they joined the demonstration.

Over the next few days, more than 200,000 strikers marched from the workers’ districts across the bridges into the city centre, joined by students and middle-class protesters (something like the Tahrir Square events in Egypt in 2011). On Bloody Sunday, 26 February, soldiers fired on the crowds, killing hundreds of unarmed protesters.

The next day, many regiments mutinied and turned on the armed police. The government completely lost military power in the capital, leading to the abdication of the tsar and an end to 300 years of absolute rule by the Romanov royal family.

Mass nonviolent action played a crucial role in winning soldiers in Petrograd over to the revolution. In the largest sense, it was the willingness of tens of thousands of unarmed civilians to come out on the streets, day after day, despite the shootings and the beatings, that wore away at the ‘morale’ and ‘discipline’ of the regular soldiers, even the brutal cossacks. People in the crowds also reached out the hand of friendship to the soldiers, even after the mass shootings.

Historian Orlando Figes points to a key moment on 25 February, when a squadron of cossacks blocked thousands of people marching towards the city centre:

Historian Orlando Figes points to a key moment on 25 February, when a squadron of cossacks blocked thousands of people marching towards the city centre:

‘A young girl appeared from the ranks of the demonstrators and walked slowly towards the Cossacks. Everyone watched her in nervous silence: surely the Cossacks would not fire at her? From under her cloak the girl brought out a bouquet of red roses and held it out towards the officer. There was a pause. The bouquet was a symbol of both peace and revolution. And then, leaning down from his horse, the officer smiled and took the flowers. With as much relief as jubilation, the crowd burst into a thunderous “Oorah!” From this moment, the people started to speak of the “comrade Cossacks”, a term which at first sounded rather odd.’

On Red Monday, 27 February, British author and journalist Arthur Ransome telegraphed home an example of how the regime crumbled:

‘Went up towards Duma [the parliament] with troops being led against revolutionaries stop battle proceeding in Liteiny district where new troops ordered fire hesitated moment then in extreme brotherly love handed over their rifles to crowd stop.’

Russia then entered a period of ‘dual power’, ruled both by a Provisional Government (made of a mix of political parties) and by soviets (directly elected by workers, peasants and soldiers).

Civilian defence

In late August, general Lavr Kornilov, commander-in-chief of the Russian army, tried to mount a coup against the Provisional Government. He moved elite, loyal units from the front to take Petrograd – only to be defeated by civil resistance.

At Vyritsa, just 37 miles from Petrograd, railworkers blocked the way with railway cars full of timber, and tore up the tracks for miles, in order to stop regiments from the ‘Savage Division’. This division was made up mainly of Muslim mountain people from the northern Caucasus known for being ferocious in battle.

The stranded Caucasian soldiers were mobbed by people from local soviets, factories and regiments. A Muslim delegation turned up, sent by the Executive Committee of the Union of Muslim Soviets, as well as a group of nearly 100 sailors who had previously been attached to the Savage Division. Among the Muslims was the grandson of a revered Caucasian fighter and imam, the legendary Shamil.

After two days of debate and discussion, the Savage Division elements in Vyritsa arrested their commandant, formed a revolutionary committee and held a meeting with representatives of all units in the division, and with the Muslim delegation. The gathering voted to send a delegation to Petrograd to make clear their loyalty to the Provisional Government.

It was a similar story with the Ussurisky Mounted Division and the First Don Cossack Division, two crack units previously seen as unquestioningly obedient, stopped in different locations by nonviolent sabotage and won over by persuasion.

Soviet forces had carried out huge military preparations around Petrograd, digging trenches, laying fortifications and arming workers. They turned out to be irrelevant to Kornilov’s defeat.

‘Our strongest weapon’

The last act of the October Revolution is the most famous: the ‘storming’ of the Winter Palace by red guards and the destruction of the Provisional Government, bringing about soviet rule. It didn’t happen quite that way. Bolsheviks did their best to avoid bloodshed all day, and the ‘storming’ of the palace was close to Gandhian.

One Bolshevik military commander, Nikolai Podvoisky, wrote later: ‘We did not open artillery fire [for over 10 hours], giving our strongest weapon, the class struggle, an opportunity to operate within the walls of the palace.’ Revolutionary persuasion was the core of their military strategy.

First, defenders were given encouragement and plenty of opportunities to leave. This reduced the ranks of defenders massively (and removed four of the six artillery guns in the palace). Late on, Bolshevik commanders Grigorii Chudnovsky and Petr Dashkevich went into the palace in separate bids to convince cadets to leave peacefully, which half of them did.

Around 11pm, the Bolsheviks began artillery fire from the Peter and Paul fortress, without doing much damage to the building.

Then soviet forces started entering in numbers without firing their weapons. Earlier, Bolshevik military leaders had used human wave occupations (without gunfire) to take over the army headquarters and other key buildings. One of the ministers trapped in the Winter Palace, Pavel Maliantovich, later wrote an account of the last hour of the Provisional Government:

‘Again noise.... By this time we were accustomed to it. Most probably the Bolsheviks had broken into the palace once more, and, of course, had again been disarmed.... Of course, this was the case. Again they had let themselves be disarmed without resistance. Again, there were many of them.... How many of them are in the palace? Who is actually holding the palace now: we or the Bolsheviks?’

One of the defenders of the Winter Palace, an army officer, wrote later:

‘Small groups of red guards began to penetrate the palace [to try to win over the defenders]. While the groups of red guards were still not numerous, we disarmed them, and this disarming was accomplished in an amicable way, without clashes. However, these red guards grew more and more numerous. The sailors and soldiers of the Pavlov Regiment made their appearance. A disarming in reverse began – of the Junkers [cadets], and once again it was done in a rather peaceful fashion.... [When the end came] large masses of red guards, sailors, Pavlovtsy [soldiers from the Pavlovsky regiment] entered the Winter Palace. They did not want bloodshed. We had to surrender.’

Earlier, around 2.35pm on 25 October, Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky reported to the Petrograd Soviet: ‘In the history of the revolutionary movement, I know of no other examples in which such huge masses were involved and which developed so bloodlessly.’