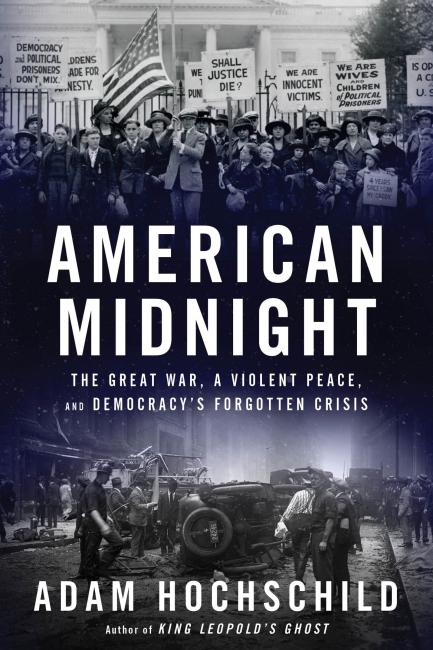

Adam Hochschild’s latest book tells the story of the extraordinary wave of repression that took place in the US during the years 1917 – 1921.

Brilliantly told, it’s ‘a story of mass imprisonments, torture, vigilante violence, censorship [and] killings of Black Americans’, kickstarted by the USA’s formal entry into the First World War in April 1917.

But it’s also the story of incredible bravery and resilience on the part of those who resisted this madness.

Then-US president Woodrow Wilson claimed that the US had had its belligerent status in the war ‘thrust upon it’. However, as Hochschild makes clear, ‘if anyone had thrust war upon the country, it was the United States itself, by becoming a bastion of the British and French military.’

Indeed, at the time, the US ambassador in London reported that: ‘Perhaps our going to war is the only way in which our present preeminent trade position can be maintained and [a recession in the US] averted.’

The domestic crackdown began at once, drawing on pre-existing anti-immigrant movements, lessons learned in the United States’ recent brutal counter-insurgency campaign in the Philippines, and the country’s deeply-rooted culture of racism.

The Espionage Act of 1917 ‘defined opposition to the war of almost any sort as criminal’ with penalties including ‘a fine of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for not more than 20 years’. (Julian Assange was recently charged under an amended version of the Act.)

Its successor, the 1918 Sedition Act, went still further, making it a crime to ‘utter, print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States’.

In 1917 and 1918 alone, more than 1,000 people were convicted under the two Acts ‘for voicing criticisms of the war effort or the government’.

For example, filmmaker Robert Goldstein was sentenced to 10 years in prison after the opening in 1917 of his silent film about the US war of independence, The Spirit of ’76 – which had been made prior to the US joining the First World War.

Goldstein’s crime? The film’s portrayal of the British (now US war allies) was considered too unsympathetic.

Several states banned the teaching of German in school. Others banned the use in public of all foreign languages.

Hundreds of issues of US newspapers and magazines were banned from postal services (the equivalent, today, of preventing a media outlet from using the internet) and a lavishly-financed government propaganda agency with 75,000 speakers was created. (One of the agency’s architects wrote: ‘The force of an idea lies in its inspirational value. It matters very little whether it is true or false.’)

In total, ‘more than 450 people… [were] imprisoned for a year or more by the federal government, and an estimated greater number by state governments, merely for what they wrote or said.’ (The last victims of these jailings were not released until June 1924.)

This period also saw the formation of a nationwide group of vigilantes: the American Protective League, an official arm of the department of justice with more than a quarter of a million members.

Despite a publicly-cultivated hysteria about enemy spies (in reality, there were few left in the US by 1917), much of the repression targeted the labour movement and the left more generally – most notably the Socialist party, then a significant political force.

Strikers were forced from their beds at gunpoint and deported en masse across state lines. Members of the nation’s most militant union, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), were tarred-and-feathered by masked mobs – and in some cases lynched.

The leader of the Socialist party, the saintly Eugene Debs, received a 10-year sentence for having stated publicly that ‘in all the history of the world you, the people, never had a voice in declaring war’.

He was not released until Christmas day 1921.

In 1918, almost 100 IWW activists were prosecuted in what remains ‘the largest civilian criminal trial in American history’.

None were charged with acts of violence, only for ‘words they had spoken or written’. All were found guilty on all counts, with the judge handing down 807 years in prison time and fines totalling more than $2mn.

The poet and songwriter Ralph Chaplin, who got 20 years, told the judge: ‘I am proud to have climbed high enough for the lightning to strike me.’

Meanwhile, some 450 ‘absolutists’ – who refused not only combat, but also noncombatant war service – served time in harsh military prisons, where some had their wrists shackled to their cell bars to ‘force them to stand on tiptoe for eight hours a day’. Others were beaten, stabbed with bayonets and threatened with summary execution.

Incredibly – and revealingly – the repression actually escalated after the war ended in November 1918. Reflecting this, roughly half of the book covers this latter period.

For example, ‘[m]ore Black Americans died violently at the hands of their white countrymen’ in the so-called ‘Red Summer’ of 1919 ‘than had in decades’, with large-scale violence erupting in over two dozen cities, almost all of which began as white riots.

Federal troops carried out most of the more than 103 killings of African-Americans in Phillips county, Arkansas, that year – ‘white property owners were infuriated that Black sharecroppers were organising a union’. Their commander, a veteran of the Indian wars, ordered his soldiers to ‘kill any negro who refuses to surrender immediately’.

The infamous ‘Palmer raids’ of late 1919 and early 1920 saw some 10,000 people seized and interrogated.

As with his previous works of public history, Hochschild has assembled a vivid and memorable cast of real-life characters to weave his narrative around.

These include some well known figures – Debs and Emma Goldman on the heroic side, Woodrow Wilson and J Edgar Hoover on the other – but also many less familiar names.

For example, Marie Equi, a more-or-less openly gay woman, who opened a medical practice in Portland, ignored the laws about distributing birth control and treated her poorer patients for free. A state leader in the battle for women’s suffrage, she had an affair with Margaret Sanger and ‘outdid any woman of her time in her willingness to battle for what she believed in with her fists’.

In 1916, Equi scaled a telephone pole, unfurling a banner reading ‘DOWN WITH THE IMPERIALIST WAR’.

Despite pleas from the police, local fire fighters ‘were in no rush to harass the Doc who cared for their families’, noted one account.

Later indicted under the Espionage Act, Equi was sentenced to three years imprisonment, which she only began serving in October 1920.

Other memorable characters include A Mitchell Palmer and Louis F Post.

A Quaker who turned down a request to become secretary of war because of his ‘pacifist principles’, Palmer went on to become a zealous advocate of mass arrests. As US attorney general, he planned to deport tens of thousands of people from the US.

A former federal prosecutor and founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), Post served as acting secretary of labour for a mere six weeks. During this brief period, he was able to invalidate thousands of ‘Palmer raid’ arrests, and prevent some 2,000 deportations. Moreover, he later successfully faced down Palmer’s attempts to impeach him for these actions.

Over 100 years later, we are all still living with the legacies of this period.

Had the Socialist party not been effectively crushed, Hochschild suggests: ‘it might well have pushed the mainstream parties into creating the sort of stronger social safety net and national health insurance systems that people take for granted in Canada and Western Europe today.’

This period also laid the groundwork for the passage of the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, which ‘placed the most severe restrictions on immigration in American history… barr[ing] Asians from the country entirely’ and providing only ‘a tiny quota of slots to other immigrants’.

Still in place at the time of the Second World War, this Act would prevent the US from offering refuge to countless men, women and children attempting to flee the Nazi Holocaust.

This period also played a crucial role in the development of the modern surveillance state.

‘Until 1917’, Hochschild notes, ‘surveillance in [the US] had been almost entirely the work of private detectives’ but ‘the paranoia ignited by the First World War empowered government intelligence agencies, both military and civilian, to do their own spying and infiltrating.’ (Hoover, later infamous as the director of the FBI, also rose to prominence during this time as chief of the Radical Division, compiling lists of ‘subversives’ for the justice [sic] department.)

In his prologue, Hochschild writes of his hope that by examining a period in which ‘the toxic currents of racism, nativism, Red-baiting and contempt for the rule of law [that] have long flowed through American life’ engulfed the country, ‘we can understand them more deeply and better defend against them in the future.’

With those currents alive and well – and not just in the US – this is surely a hope we would all like to see realised.