Those who sheepishly admit to 'doing art', myself included, are sometimes embarrassed to connect it with politics. The term 'art' is troubling; why not just call it 'play'?

Those who sheepishly admit to 'doing art', myself included, are sometimes embarrassed to connect it with politics. The term 'art' is troubling; why not just call it 'play'?

Music, painting or whatever should be satisfying in itself; and radical politics shouldn’t be used to prop up mediocre art – not to mention the danger of thinking that having a jam in your bedroom is activism!In the late 1950s, a group of European radicals (including Guy Debord and Asger Jorn) found my favourite solution to this quandary. The group sought to alter the solidified lived experience created under post-war capitalism, in which many workers found themselves merely lubricating the process of capital instead of producing tangible things – think of modern-day call centres.

Advertising and celebrity-worship shore up this life of 'mere representation', but (the thinking went) it can all be constructively rejected by subversion and play.

What later became known as ‘Situationism’ was a starting point from which to make art _and_ challenge social norms. Art and politics were inseparable, and daily, live art ‘situations’ would subvert the oppression of fixed images.

Though the early 1970s saw the end of Situationist activity, the third sector (or service industry) has grown to dominate the UK economy. Alienated wage labour rules the land, and Debord’s motto, ‘Never work’, is more relevant than ever, meaning we should find enjoyable, meaningful occupations as we – not corporations of bureaucrats – choose to define them.

The Situationists imagined life without the term ‘art’, as daily life would be completely marinated in it.

There would be no isolated ‘professionals’; each individual would be a participant in joyful subversion. This would take place on the streets, as knowledge and art would be free from the restrictions of galleries and sterile libraries. We would collectively turn upside down 'the whole of urban life into a space of collective play and poetry'.

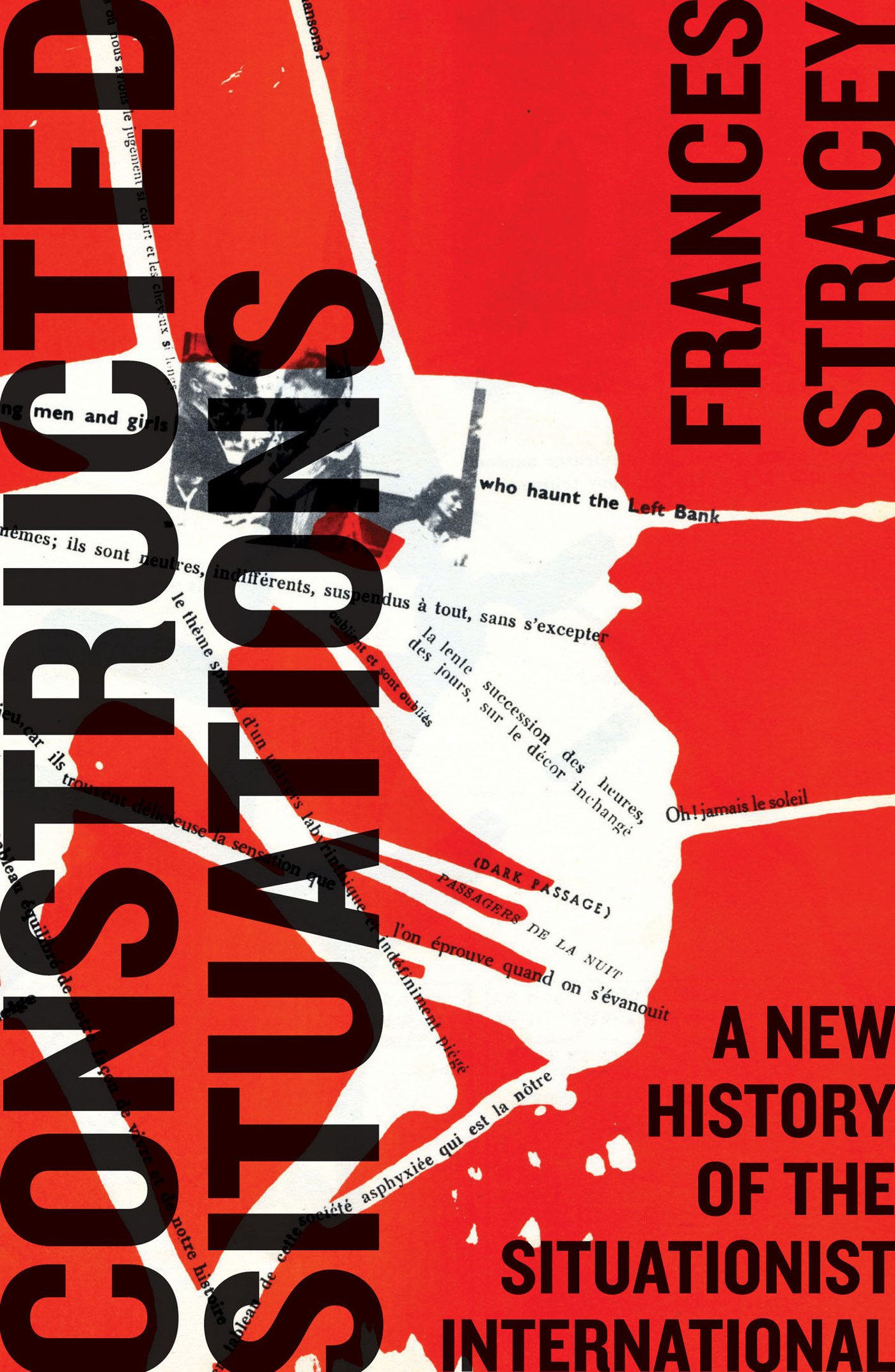

One of their most famous lines of graffiti comes to mind: 'Under the paving stones, the beach'.Alongside generous space for images of radical graffiti, industrial painting and subversive texts, Stracey also highlights examples of events supporting Situationist theories, from the Watts Riots and the Paris protests in May 1968, to more recent ventures such as digital hacktivism and Reclaim the Streets.

Though the text's denser parts require a little sifting to discover the gems and moments of revelation, the persistent reader will have their efforts rewarded (for easier reading on DIY living and self-organised art, the writer and musician Andy Abbott publishes his texts available to read online

for free)!

Crucially, Stracey never commits the cardinal sin of taking her project too seriously.