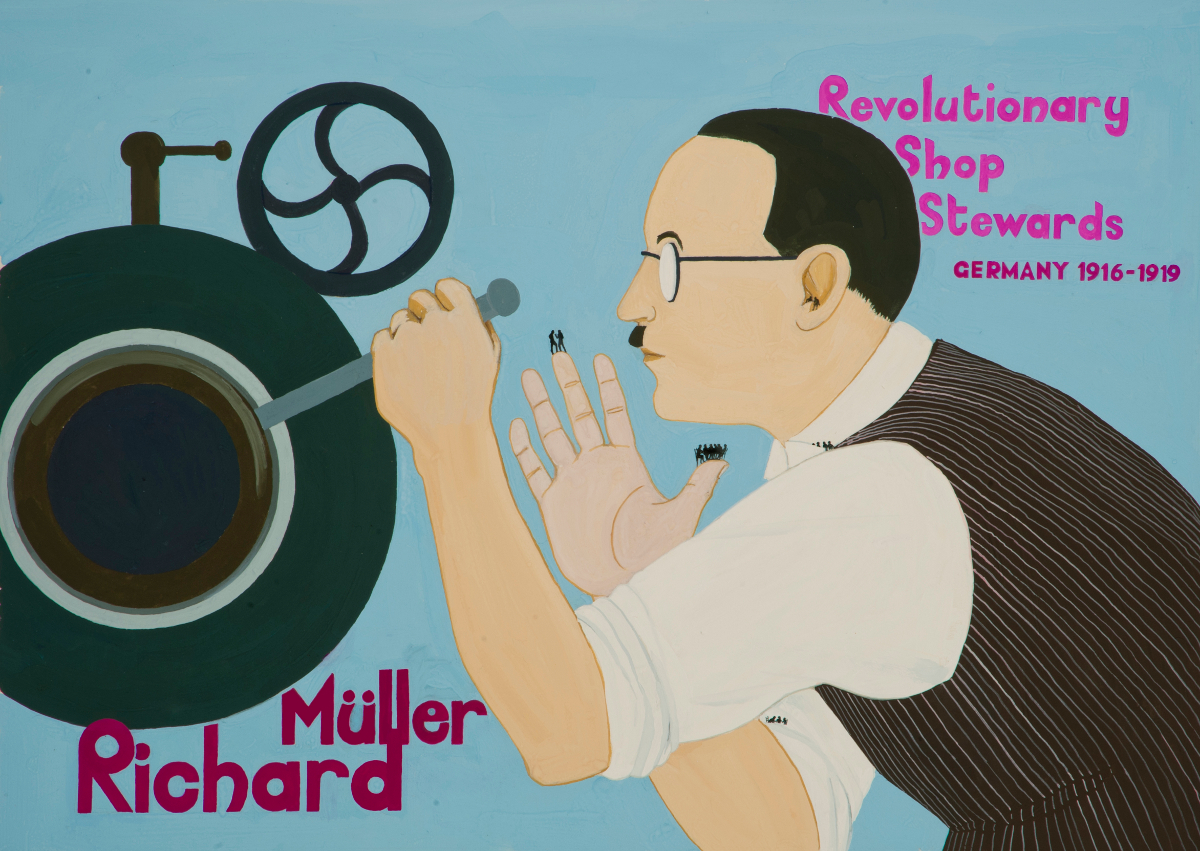

Richard Müller & the Revolutionary Shop Stewards

by Emily Johns

“How did the workers’ councils emerge in Germany? They emerged from the big strike movements of the last years, in which we — who have always been strong opponents of the war and who have lived with tortured souls for four years given the pressure and the lies the German people were exposed to — were the driving political force. We convinced the people in the big factories who shared our ideas to act as workers’ councils; they did so under enormous danger.” - Ernst Däumig, 19 December 1918

“All political questions are in the end questions of power.” - Richard Müller, 16 December 1918

On 28 June 1916, Karl Liebknecht – Germany’s most famous anti-war campaigner – was put on trial for treason for his opposition to the war. That same day, some 55,000 munitions workers left their workplaces to march in perfect discipline through the streets of Berlin, shouting ‘Long live Liebknecht!’ and ‘Long live peace!’. About 120 miles to the west, in Brunswick, an estimated 60 per cent of the workforce in some 65 factories also joined the strike.

Astonishingly, these events had been organised with less than 24 hours’ notice.

They were the brainchild of Richard Müller, leader of a clandestine network within the German Metalworkers Union (DMV) that would later call itself the Revolutionary Shop Stewards.

Over the next two-and-a-half years, Müller would organise two more anti-war strikes (each bigger than the last), be conscripted into the army three times, and play a leading role in the largely-bloodless popular overthrow of the kaiser in November 1918.

The night before the revolution reached Berlin, Müller watched as heavily-armed soldiers marched by in endless rows, and became convinced that the uprising would be drowned in blood. But, the next day, the workers carried red flags and placards addressed to the garrison troops saying ‘Brothers, no shooting!’, and hardly a soldier was prepared to fire on them.