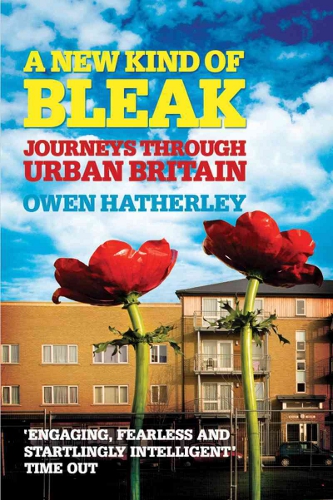

In his latest book on the built environment, Owen Hatherley visits 17 towns and cities across Britain, presenting an architecturally-inflected state of the nation.

In his latest book on the built environment, Owen Hatherley visits 17 towns and cities across Britain, presenting an architecturally-inflected state of the nation.

Part travelogue, part searing political critique, the book takes the form of a series of ‘urban trawls’, bringing the author to ‘some extremely unlovely places’: the Thames Gateway, Belfast, Birmingham, the City of London (‘the satanic site at the heart of the UK’s malaise’).

On each journey, Hatherley finds a Britain failing in intellect and imagination, everywhere reflected in the cityscape he encounters.

The built environment is cleverly used as a visual and material anchor to address issues that will interest anyone concerned with questions of power, social justice and the role of the state in planning public space. There is insightful discussion of Occupy, for example, and of the ‘security landscape’ at a day of protest in the City of London.

The relentless drive to clear the inner city of the working class in order to liberate lucrative real estate is a clear thread throughout. From the ‘regeneration’ mania of the New Labour era to the increasingly extreme free market ideology of the present government, the developments Hatherley observes springing up are catering for the newly-urbanising middle class, a much more profitable and socially docile population.

The sop of quotas for ‘affordable’ or ‘social’ housing in such places belies the fact that little if any effort is being made to think about, design or build adequate municipal housing. Inequality is being designed-in.

Hatherley contrasts this with the architectural utopianism of many ’60s mass-housing projects, such as Robin Hood Gardens or the Barbican in London. The thoroughness of their design and the desire to create truly egalitarian spaces for tenants is a testament to a time when ‘things now considered impossible were once considered normal’.

Hatherley attempts to present such places as positive proposals for the future, whose spirit could be recaptured for the present day. However, these proposals are developed little further than a misty-eyed nostalgia for ‘streets in the sky’ and the ‘power and melodrama’ of the brutalist style.

The writing is sharp and often very funny, and the discussion is wide-ranging, but at the end of the book the reader is left unclear what exactly is being proposed and what political changes would need to be forced in order to get there.

While there is an absence of coherently developed alternatives to the failing urban environments he describes, Hatherley’s astute and provocative analysis reaches deep into many of the inequalities that exist for the 80 per cent of us who live in urban areas.