Longtime PN readers will know that I’ve long been a fan of Norman Finkelstein’s work. Nonetheless, I almost didn’t read this book.

I’d seen Finkelstein online recently, defending the moral (if not the legal) ‘right’ of Russia to invade Ukraine and raging about pronouns (‘Whenever I see he/ him or she/her, I think fuck/you’). And, frankly, I wondered if he’d lost the plot.

But I’m glad that I tracked his new book down and (with some qualifications that I’ll come to) would strongly recommend it to others.

As Finkelstein explains in the foreword, the book had its origins in the ‘Letter on Justice and Open Debate’, decrying the excesses of ‘cancel culture’, that appeared in Harper’s magazine in 2020.

Finkelstein himself was hounded out of academia for having exposed a series of frauds and hoaxes relating to the Israel- Palestine conflict, most notably Alan Dershowitz’s 2003 book The Case for Israel.

In 2020, his then-publisher proposed that he ‘join the debate with a short book’. What emerged was obviously not what had been expected.

Rather than focusing his attack on right-wing and liberal hypocrisy over free speech (of which there is, of course, plenty), Finkelstein had a very different set of targets in mind. And it appears that no mainstream publisher – or even the bigger radical ones – would touch it. Hence its publication by the hitherto little-known Sublation Press.

The core thesis of this big and baggy book is that, while previously a marginal affair ‘pretty much confined to the college campus and the political left’, a certain damaging brand of identity politics (‘woke politics’) has now become ‘ubiquitous’ in US politics – and that it has done so as a consequence of the Democratic party substituting ‘“oppressed minorities” of every imaginable ilk’ for what used to be its mass base: the trade union movement.

Finkelstein is furious that this ‘has distracted from and, when need be, outright sabotaged a class-based movement that promised profound social change’ – namely the mass grassroots movement supporting Bernie Sanders’ presidential bids in 2016 and 2020.

Finkelstein writes movingly about the 2020 protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, where he was heartened to see ‘the naturalness with which white and nonwhite millennials commingled, and the sincere outrage of the white youth against racist cops’. Indeed, he writes, these white youth appeared to be raging ‘not just against the knee casually pressed on Floyd’s neck but also, at the same time, against the Machine that has wrecked their present and cancelled their future.’

Yet, as Finkelstein documents in voluminous detail, the brand of identity politics he’s attacking ‘counsels Black people not to trust whites, as their racism is so entrenched and so omnipresent as to poison their every thought and action. It conveys to poor whites that they, no less than the white billionaire class, are beneficiaries of racism, so that it would be foolhardy of them to ally with Black people. It fractures, splinters, fragments a natural and necessary alliance of the have-nots by splicing and dicing them into, literally, an infinitude of subgroups, each of which insists on parity representation in any coalition, creating a cacophony of demands and preempting any possibility of that broad unity and solidarity which, alone, can defeat the organized, ramified power of wealth.’

In other words, it ‘divid[es] the many so as to, designedly or not, enable the few’.

Moreover, this kind of identity politics ‘puts forward demands that either appear radical but are in fact politically inert – Defund the police, Abolition of prisons – as they have no practical possibility of achievement; or that leave the overall system intact while still enabling a handful, who purport to represent marginalized groups to access – on a “parity” basis – the exclusive club of the “haves”.’

According to Finkelstein, ‘a huge political opportunity’ was squandered during the George Floyd protests in 2020: ‘If the “Jobs and Freedom” slogan of the 1963 March on Washington had been tweaked so that the demand “Justice and Jobs” seized the moment, the nascent coalition in the streets between an antiracist and anti-capitalist politics could have consolidated around concrete political demands.... Instead the demonstrations petered out amidst radical posturing and vacuous identity politics’.

On radical-sounding slogans divorced from reality, Finkelstein memorably quotes Trotsky: ‘“if you have not even a bridge to them, not even a road to the bridge, nor a footpath to the road” then they amount to a “fetish... a religious myth. Mythology serves people as a cover for their own weakness or at best as a consolation.”

The book is split into two parts, which can be read independently according to the reader’s interests.

The first, which comprises roughly fourth-fifths of the book, focuses mainly on identity politics. The second on questions to do with academic freedom.

Chapter 1 (‘Confessions of a Crusty, Crotchety, Cantankerous, Contrarian, Communist Casualty of Cancel Culture’) sets the stage, and also outlines John Stuart Mill’s classic defence of free speech: you could be wrong; you shouldn’t prevent others from deciding for themselves; engagement with false claims helps to prevent true beliefs becoming ‘dead dogmas’; even false ideas may get certain things right and so should be heard.

The remainder then uses close reading of a series of key texts and memoirs to expose the hollowness and pernicious impact of both the form of ‘identity politics’ that Finkelstein is attacking and the Obama presidency. Readers of his earlier works on the Israel-Palestine conflict and the Nazi Holocaust will immediately recognise the approach adopted.

Needless to say, Finkelstein is not the first person to attack ‘identity politics’ from the left. But these in-depth analyses form a valuable, as well as a novel, contribution.

First up is Kimberlé Crenshaw, famous for having coined the term ‘intersectionality’.

Gleefully pulling apart the core claims of her seminal paper on the topic, Finkelstein enlists the services of a friendly mathematician to detail how – taken literally – her claim that any two categories of oppression combine to create ‘an entirely new, irreducible category of oppression’, leads to the existence of infinitely many such categories.

He also notes how Crenshaw’s claims about corporations ‘outdistancing’ Democratic candidates on ‘structural racism’ (during the 2020 elections) were used to attack Sanders.

Yes, Jeff Bezos had posted a ‘Black Lives Matters’ banner on the Amazon website, committed $10 million (out of his $100+ billion fortune) to fighting racism, and announced that 19 June (the anniversary of the emancipation of enslaved African-Americans) would now be a company holiday.

Yet, Finkelstein asks, was this really ‘outdistancing’ the Sanders platform of Medicare for All, raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour, eliminating college tuition fees, and abolishing student debt?

After a brief look at Ta-Nehisi Coates on reparations (for slavery) and the cynical weaponisation of the latter by Sander’s opponents in the Democratic party (‘who knew full well that a substantive reparations bill was dead-on- arrival’), the focus shifts to Robin DiAngelo, author of the million- selling New York Times best-seller White Fragility.

A transparent huckster, DiAngelo apparently charges thousands per gig for her ‘therapy’ sessions to ‘interrupt’ racism – a phenomenon which, she claims, ‘pervades every vestige of our reality’.

Unsurprisingly, she has been enthusiastically embraced by business leaders.

As Finkelstein notes, her shtick ‘performs for the powers-that-be the useful function of pretending to fight racism while leaving all the institutions and structures sustaining it intact’.

However, the book’s two longest critiques – comprising roughly two-fifths of its total length – are devoted to Ibram X Kendi and the Obama administration.

Kendi is the author of the self- proclaimed ‘definitive history of racist ideas in America’, Stamped from the Beginning, which won a National Book Award. This was followed by his 2019 book: How to Be an Antiracist.

After reading Finkelstein’s 116-page demolition of these two works, it’s hard to disagree with his assessment that Kendi is ‘neither scholar nor activist’ but a ‘race hustler’. (Kendi apparently charges $207 a minute for his lectures.)

The ‘sole innovation’ of Kendi’s ‘definitive history’ is ‘to affix the racist/antiracist tag on each of the characters’ that appear – labels that he ‘hurls... with total abandon’.

Whoever and whatever doesn’t ‘burnish his trendy brand’, Finkelstein notes, is deemed ‘racist’. Indeed, Kendi’s list of ‘racists’ includes Black Abolitionist Sojourner Truth (herself an escaped slave), white Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and Martin Luther King Jr!

Moreover, Kendi asserts that it’s racist to believe that slavery damaged Black people (according to him they were able to ‘dance into freedom without skipping a beat’) and even appears to claim that Black people are worse off today than they were under slavery.

Finkelstein also convincingly demonstrates that Kendi ‘mangles the historical record’ on multiple counts.

For example, Kendi ‘den[ies] that the Civil Rights Movement was the prime mover in extirpating the deeply entrenched Jim Crow system’ in the American South, which he instead depicts as ‘wholly the work of white people oblivious to, insulated from, and untouched by the mass protests’.

‘If Kendi is currently feted in charmed circles,’ Finkelstein notes ‘it’s because, for all his fire and brimstone rhetoric, his hip and hyped public persona, his militant preening and macho posturing, the only substantial demand he makes on the one percent – reconfigure the exploiting class to include a fair percentage of us – they’re already prepared to concede’.

In the next chapter, Obama is condemned for being ‘a stupefying narcissist’ who ‘stood for nothing except himself’ – and was therefore the ‘perfected and perfect instrument’ of the form of identity politics that is the focus of Finkelstein’s justifiable wrath.

Obama’s candidacy, Finkelstein notes, ‘was built on a big lie’. This was ‘that the radical break represented by the election of a Black man as president would presage a radical change in the body-politic’.

In his memoir, Promised Land, Obama boasts of the ‘neat trick’ that he had pulled off during his electoral campaign: running as a ‘blank canvas upon which supporters across the electoral spectrum could project their own vision of change’.

In reality, Finkelstein notes, even the chief strategist for Obama’s presidential campaigns, David Axelrod, concedes that ‘neither he nor Obama nor anyone else in Obama’s entourage ever contemplated a decisive rupture with the past’.

In addition to the man himself, Finkelstein also examines the memoirs of a ‘supporting cast’ that includes two of Obama’s chief speech writers; his senior adviser, Valerie Jarrett; his gofer, Reggie Love; and White House deputy chief of staff Alyssa Mastromonaco.

Perhaps most interesting for PN readers is Finkelstein’s devastating take-down of Obama’s ambassador to the UN, Samantha Power.

The ‘[s]elf-styled public conscience of the Obama administration’, Power had previously written the 2003 Pulitzer-winning book, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide.

Once again, Finkelstein exposes the yawning chasm between public reputation and sordid reality, detailing Power’s ‘maniacal support for military intervention in Libya that destroyed the country; her feverish advocacy of armed intervention in Syria... that could only have exacerbated the humanitarian catastrophe there; [and] her silence in the face of, or aggressive complicity in, human rights crimes committed by the US and its allies’.

During the Obama presidency, US drones are estimated to have killed over 3,000 people in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia, including upwards of 400 civilians. Despite this, Power’s 2019 memoir, The Education of an Idealist, fails to even mention the existence of these silent wars – or the devastating war in Yemen, where US arms and intelligence supplied during Power’s ambassadorship helped to create one of the world’s worst humanitarian disasters.

Likewise, Power is ‘thunderously silent’ on the August 2013 massacre of over 900 protesters in Egypt (‘one of the world’s largest killings of demonstrators in a single day in recent history’, according to Human Rights Watch), though the supply of US military equipment to the coup regime restarted in 2015, again during her tenure.

Power also has ‘not one word’ to say about Israel’s murderous assaults on Gaza during the Obama presidency, though she ‘worked assiduously behind the scenes after each massacre to shield Israel from accountability’. (In 2014, Operation Protective Edge systematically targeted and destroyed 18,000 Gazan homes, killing 1,500 Gazan civilians, including 550 children.)

Power ‘wasn’t just a disaster’, Finkelstein concludes, ‘she was downright evil’.

An exposé of cynicism, intellectual vacuity and radical posturing could easily end up a worthy-but-dull affair. Fortunately, this section of the book is leavened by extensive quotation from two of the giants of the Black freedom struggle: Frederick Douglass and WEB Du Bois, whose words and lives stand as further rebuke to those currently debasing their legacy.

Perhaps surprisingly, Douglass – who had escaped from slavery, becoming one of the Abolitionist movement’s most effective campaigners – opposed ‘race pride’, asserting: ‘I recognize and adopt no narrow basis for my thoughts, feelings, or modes of action. I would place myself, and I would place you, my young friends, upon grounds vastly higher and broader than any founded on race or color.... Whoever is for equal rights, for equal education, for equal opportunities for all men, of whatever race or color – I hail him as a “countryman, clansman, kinsman and brother beloved”.’

I’m sure that I won’t be the only reader who finished the book eager to read more of both Douglass and Du Bois.

Part 2 of I’ll Burn That Bridge When I Get To It – an extract from which appeared in PN 2648 – 2649 – turns to questions of academic freedom. Finkelstein argues, seemingly paradoxically, on free speech grounds, that if Holocaust denial really poses a serious threat to society then there is a strong case for having deniers present their ideas at universities ‘if only to inoculate students’.

Holocaust denial is serving here as a placeholder for any ‘politically toxic’ factual claim. Finkelstein is himself the son of Holocaust survivors.

The book then proceeds to examine questions such as: ‘Should a professor who expresses “outrageous” opinions on morality outside the classroom have the right to teach?’

Four historical cases are considered, the best-known of which are those involving Bertrand Russell (who was prevented from teaching mathematical logic at the College of the City of New York in 1940, because of his publicly-stated attitudes towards sex and marriage) and Angela Davis (who was briefly suspended from a teaching post at UCLA because of her membership of the Communist party).

Significantly, given his stance regarding free speech in relation to matters of truth, Finkelstein accepts that there are still some legitimate limits on professors’ extramural speech – at least if they want to keep their jobs: ‘a professor’s public exhortation to pursue certain modes of conduct [for example, paedophilia] must be reckoned a step too far’.

While the material in this section is interesting, the precise conclusions to be drawn are (to my mind) murkier, as befits the topic.

Throughout, as readers of his earlier books would expect, Finkelstein brings his famously forensic approach to bear on the issues at hand. He’s put the hours in and done his homework, displaying impressive command over a vast range of material.

For the densely-footnoted, 38-page section ‘Was WEB Du Bois a racist?’ (part of the chapter on Kendi), Finkelstein read (or re-read) six ‘representative’ works by Du Bois, as well as David Levering Lewis’ massive biography. Similarly, for the Obama chapter, Finkelstein clearly had to read and make extensive notes on at least a dozen memoirs, biographies and collections of speeches. By my reckoning, these two sets of material alone clock in at over 10,000 pages.

On the other hand, none of this should come as a surprise. After all, Finkelstein read scores of the 500-page volumes in Gandhi’s Collected Works when preparing his tiny 100-page book, What Gandhi Says: About Nonviolence, Resistance and Courage (see PN 2547 – 2548).

More of a departure is Finkelstein’s decision to deploy a wider range of styles and materials than he’s done previously: poems, imagined dialogues, a ‘film script’, extracts from popular songs, extracts from films (Mike Leigh’s Life is Sweet) and novels (quotes from Sinclair Lewis’ Elmer Gantry, about a hypocritical evangelical preacher, are inset throughout the chapter on Obama), a section written in faux Black vernacular (mocking DiAngelo’s ‘down with the hood’ pretensions) and some innovative uses of typography.

I’m not sure how much any of this added, but on the whole it didn’t get too much in the way.

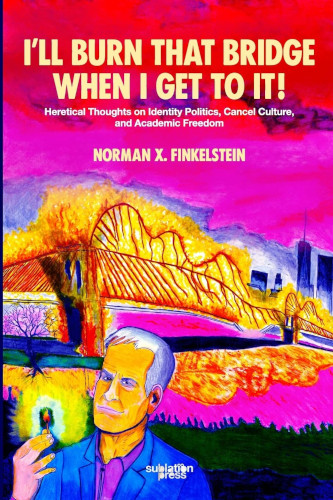

The cover, on the other hand, is hideous. I could also have done without the running joke about Obama’s acolytes and adulators all lusting after him (‘Although he professes that he and his students blissfully contemplated together the “curvature” of the Constitution, it’s more probable that Tribe was contemplating the curvature of his student’s constitution.’).

This is also, undeniably, a book of digressions, as well as a book that is (in Finkelstein’s own words) ‘laced with vitriol’.

The former include reflections on Bill Clinton (who in terms of his work ethic and restless intelligence clearly stands head- and-shoulders above Obama), the history of eugenics in the US, and the logic (or lack thereof) of some of the US supreme court’s most famous decisions.

This material is often fascinating, but at the same time one can understand why a senior vice president at publisher Henry Holt returned the book’s manuscript with the comment that: ‘there’s altogether too much of everything’.

Now the caveats.

First is Finkelstein’s unfortunate decision to use the word ‘woke’ to refer to the particular brand of identity politics that he’s attacking.

This is an unfortunate choice for several reasons, not least that the term is often used indiscriminately by some on the right to mean anything and everything that they don’t like (Black people in TV dramas, history that doesn’t gloss over imperial atrocities, concern about climate change – the list is endless).

To be fair, Finkelstein does define what he means by ‘identity politics’: ‘At its core it’s about representation: a competition within the group as to who best exemplifies it, and a competition between the group and the broader community as to the former’s legitimate claims for greater representation in the latter’.

But it would have been worth pointing out that the term ‘identity politics’ was first popularised in the 1970s by the queer, Black, feminist, socialist Combahee River Collective (CRC), for whom it meant something very different.

Indeed, as Olúfémi O Táíwò notes in his recent book, Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics and Everything Else, for the CRC, identity politics was supposed to be about ‘fostering solidarity and collaboration... they were in favor of diverse, coalitional organizing, an approach that [co-founder Barbara] Smith later saw exemplified’ in the Sanders campaign, which she endorsed.

Second, Finkelstein appears to have a blindspot when it comes to trans people and is apparently unable to draw the meaningful distinction between sex and gender. So, while Finkelstein writes that transgender people deserve ‘maximum compassion, for sure’, his book nonetheless contains a small number of passages on these topics that some people are going to find very offensive.

However, it would be a shame if this were to deprive the book of the wide audience that it deserves.

This is all the more ironic given that Finkelstein states explicitly that the shifts in societal attitudes toward sexual and racial minorities in recent decades are ‘a civilizational advance, a cultural tectonic shift, in which we as a society can justly take pride’. He cites approvingly, albeit with qualifications, John Stuart Mill’s famous encouragement of ‘experiments in living’.

Thirdly, there is the question of how – and in what ways – these critiques apply on the UK side of the pond, where the brand of identity politics that Finkelstein is attacking does not appear to have been weaponised in the same way by Keir Starmer’s Labour party. (Rightly or wrongly, Labour appears to be doing little or nothing to take the ‘other side’ of the culture wars that the Tory Right are so desperately stoking.)

To summarise: this is a moving, rich and digressive work that offers a powerful and much- needed critique. Chances are, it’s likely to infuriate or offend you at some point. I encourage you to read it.