In 2018, following an application from the Jamaican government, UNESCO recognised reggae music as an ‘intangible cultural heritage of humanity’ that contributes to ‘international discourse on issues of injustice, resistance, love and humanity’.

In the same statement, UNESCO described reggae music as ‘at once cerebral, socio- political, sensual and spiritual’ and observed that the genre serves ‘as a vehicle for social commentary, a cathartic practice, and a means of praising God’ and that ‘the music continues to act as a voice for all.’

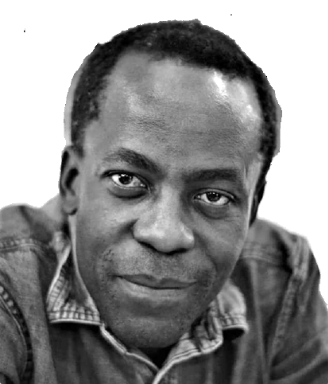

Community activist and historian, Cecil Gatzmore suggests that reggae music’s global reach and impact comes from the language, images, and metaphors it uses.

He observes that because Jamaica is a Protestant country, many of the people who grew up in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, when reggae music was emerging, were exposed to the King James version of the Bible ‘in Sunday school, in the morning service, [...] in the evening service, and at other events during the week.

‘So, you’ve got a lot of the Bible. And that’s actually a very powerful source of the imagery. All of the stuff about Rome, the anti-Roman stuff, all of the stuff about Babylon and the anti- Babylonian stuff is generated from the way in which that stuff lodges in our head as a result of the way in which we were raised.... That’s what we grew up on.’

He describes Jamaican patois, the primary language of reggae music, as extraordinarily evocative: ‘And if it has available to it, in addition to the African mythology and an African worldview, if it also has that enriched by the stuff that comes to us from Romans in the Bible or from Revelations in the Bible, you are in the presence of something that’s likely to be extraordinarily powerful.’

On top of that are the experiences of oppression that African people in the diaspora and on the African continent have been subjected to and have been enduring, resisting and fighting against for the past 500 years or more. ‘And we sing about that,’ Gatzmore says: ‘You know, “What about the Arawak Indians and the few Black man” who was on here before Columbus arrived and the fact that the Black people are still there, but the Arawaks are gone and so on.’

Gatzmore notes that both classic and dancehall reggae share this concern with issues around oppression, endurance and resistance.

‘If you listen to Yellow Man and other so-called dancehall artists, you will see that they’re engaged with exactly the same subject matter, whether it’s war or peace, love, freedom, the need for us to liberate ourselves. All of those are themes that are systemically, powerfully, effectively dealt with across the board in reggae.’

Gatzmore identifies liberation as a key theme in reggae music: ‘Whether we have Bob Marley talking about “everywhere is war” until there is freedom and equality. We have Buju Banton talking about the walk down Redemption Street and the liberation at the end of that, and so it goes on. And same, Anthony B has a wonderful song, not classic reggae at all, but magnificent, something called “Fire Pon Rome”.’

Gatzmore describes ‘Fire Pon Rome’ as a catalogue of the structures and forms of oppression that are still in place in Jamaica today and which can be seen in how the social, political and economic system in the country works.

He adds: ‘In the UK, that generation of young men that started with Aswad but include Misty in Roots and Steel Pulse, the work of all of those young men is about... Africa... but it’s also about the specifics of oppression that Africans here in the UK are experiencing at the hands of the “Babylonian system”. So, that’s what reggae music does. It speaks to roots and modes of liberation, and it also speaks to love and freedom.’

Gatzmore explains that the images, symbols and metaphors reggae music uses mean that ‘Everybody worldwide has the possibility of understanding what is being talked about.’

This extends to slavery which turns up in almost everybody’s imagination as the worst form of human oppression. ‘You don’t actually need to have been through enslavement in any recent time, as we diasporans have, to know what diasporans are talking about in music when we say or speak to a specific experience because everybody has that metaphor in their heads as something awful.’

Thus, it can be said that reggae music as a source of knowledge makes the legacies of imperialism, slavery and oppression intelligible, and it keeps open space in which those legacies are discussed together with ways of resisting and fighting against that violence.