They must have been very pleased when they finally caught him. Desperate to find him, the British had placed his friends and family under surveilliance and – after six weeks of unsuccessful hunting – had even offered a substantial reward for his capture.

Like many other Muslims in the north of Nigeria, he was opposed to fighting in the First World War for fear that he might be deployed against his fellow Muslims in the Ottoman empire.

A sergeant in Britain’s colonial army, he had persuaded 20 other soldiers to join him and deserted.

But after four months on the run, Tanko Kura – one of the very few African opponents of the war whose name we know – was finally captured.

Defending oppression

One of the ‘chief ironies’ of imperialism, notes historian Glenford Delroy Howe, is that during the First World War people throughout the colonial world ‘were called upon and many even eagerly volunteered to defend the very nations and institutions which kept them in subjugation and robbed them of their identities’.

India alone contributed over one million men (all volunteers), while over two million Africans served as soldiers and labourers.But there was also opposition and resistance to the war and its horrors by people in what is today called the Global South, as well as from the ‘fourth world’ of indigenous peoples.

Sometimes the resistance was violent, sometimes it was nonviolent. Unsurprisingly, it took place in widely-differing contexts and was seldom purely about the war.

Here we briefly survey a small number of examples from within the British empire, mostly from Africa – a few scattered fragments of a history that has still to be written.

Who cares?

Britain ‘recruited’ over a million African ‘carriers’ during the war from within its own colonies as well as from German East Africa. Of these no fewer than 95,000 died from malnutrition, disease and overwork – almost twice the number of Australian or Canadian troops who died during the war.

Among East and West African carriers, the death rate was 20% – almost double the 11.5% death rate for British soldiers. One colonial official explained that the East Africa campaign ‘only stopped short of a scandal because the people who suffered most were the carriers – and after all, who cares about native carriers?’

But even the carrier deaths were only the tip of the iceberg.

During its East Africa campaign, British forces maintained themselves ‘partly or sometimes wholly by the routine pillage of peasant settlements in their path. To deny sustenance to ravenous German units operating in the vicinity, villages were blasted and burned, leaving fields torched and livestock scattered.’1

Moreover, a majority of the adult men in the British territories bordering German East Africa had been coerced into operating Britain’s supply lines. Alongside impressment by German forces, this produced a manpower drain unparalleled since the 1870s, when Arab slavers had transported tens of thousands of Africans to the Middle East.

The result was a ‘severe impairment of the capacity for survival of those left behind’, notes historian Edward Paice. And the failure of the rains in late 1917 and early 1918 compounded this dire situation, leading to famine conditions.

New slavery

Recruitment was a contemporary euphemism for forced labour.

Indeed, as early as 1914, the blood-soaked governor-general of the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria, Frederick Lugard – who in 1906 had sent a 500-man column to ‘annihilate’ the Nigerian village of Satiru, killing 2,000 people – had ordered that ‘if the emergency is great, carriers must be impressed’.

Nwose, recruited in Eastern Nigeria in 1914, told how: ‘We came back one night from our yam farm, the chief called us and handed us over to the government messenger. I did not know where we were going to, but the chief and the messenger said that the white man had sent for us and so we must go. After three days we reached the white man’s compound.... The white man wrote our names in a book, tied a brass ticket number round our neck and gave each man a blanket and food. Then he told us that we were going to the great war.... The government police led the way, and allowed no man to stay behind.’

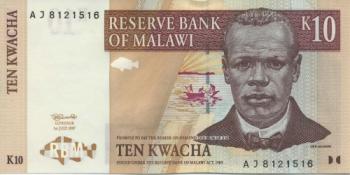

In Nyasaland (today’s Malawi), chiefs were threatened with removal from office, and sometimes whipped if they failed to produce sufficient numbers of men. ‘Recruiters’, in their turn, often used violence to impress people. ‘There was terror everywhere’, chief Malagengachanzi – a youth at the time – later recalled, ‘slavery was the actual way people were taken to war’.

British terrorism

Sometimes ‘recruitment’ was resisted violently, but these uprisings were usually swiftly repressed using extreme violence.

The best-known revolt took place in Nyasaland and was led by a Western-educated missionary, John Chilembwe.

Nyasaland had a reputation as the ‘Cinderella’ of the British protectorates, but the reality was very different. Lewis Bandawe, a migrant from Portgual’s notoriously brutal rule in Portuguese East Africa (today’s Mozambique), found the British authorities in Nyasaland little better, describing them as ‘a terror to all people’.

Spurred by the conscription of Nyasaland Africans to fight in the war, Chilembwe wrote a famous letter of protest to the Nyasaland Times (which they refused to publish) declaring: ‘Let the rich men, bankers, titled men, storekeepers, farmers and landlords go to war and get shot. Instead, we the poor Africans, who have nothing to own in this present world, who in death leave only a long line of widows and orphans in utter want and dire distress, are invited to die for a cause that is not theirs.’

In January 1915, Chilembwe and 200 of his congregants launched simultaneous attacks on the headquarters of the African Lakes Company in Blantyre and a nearby European plantation. A brutal plantation manager named William Jervis Livingston, who had destroyed several of the mission’s churches, was killed but, on orders from Chilembwe, women and children were spared.

The rising was quickly suppressed, and over 40 rebels tried and executed, their bodies left to hang in the sun as a warning to others.

Women’s curses

Resistance also took nonviolent forms.

In Nigeria, one of the most effective ways of avoiding military service was to flee into French or German territory, and similar tactics were adopted in the Gold Coast (today’s Ghana).

‘Our women curse and spit at us, asking us whether the Government, for whom we propose to risk our lives, is not the one which sends the police to our houses at night to pull us and our daughters out of bed and trample upon us.’

Throughout Nyasaland, men fled into the bush to avoid being impressed as labourers. Those caught could be brutally whipped. ‘I escaped and hid in a river and my parents, since I had not married yet, secretly brought food to me,’ Vmande Kaombe later recalled. ‘They were asked [about my absence] but they said they did not know what had become of me.’

In South Africa (a British dominion), the superintendent of native affairs in East London bemoaned the fact that when ‘recruiting meetings were in the air’ Africans ‘deliberately absented themselves and made into the bush’, while a speaker at a recruitment meeting in Pretoria complained that: ‘When we speak of joining the overseas contingent our women curse and spit at us, asking us whether the Government, for whom we propose to risk our lives, is not the one which sends the police to our houses at night to pull us and our daughters out of bed and trample upon us.’

Safe havens

In some places, African elites collaborated with the British. For example, in Nigeria the brutal emir of Zaria – who was known to indulge in slaving – became one of Britain’s best sources of troops and carriers.

However, elsewhere local elites sided with the resisters rather than the British.

In South Africa, chiefs would sometimes feign an interest in recruiting while covertly acting to thwart it. In Nigeria, in Zungeru and along the Cross river, chiefs simply refused to supply any carriers, while the people of Bende Ofufa – a section of the Ikot Ekpene district of south-eastern Nigeria – renounced all alien control, refusing to obey summonses or allow arrests, and the area became a safe haven for those on the run.

Such refusal was not risk-free though. One of the sparks for an August 1914 uprising in Egbaland in Nigeria was the arrest, humiliation and torture of an elderly chief, Shobiyi Ponlade, after the latter failed to order his people to construct and repair roads in his area without pay. Forced to remain prostrate in the sun outside the British commissioner’s house for a prolonged period, he was then beaten and left tied to a tree overnight. Subsequently imprisoned, he was dead within a fortnight.

Passive resistance

Once recruited, a range of strategies still remained for the resister, including desertion.

In South Africa, the authorities were forced to take action when it became clear that the number of recruits arriving at the Cape Town mobilisation camp did not tally with the numbers despatched to there. In the Gold Coast, over 10% of soldiers deserted.

In Nigeria, passive resistance techniques were also adopted, including hiding in the bush, malingering, discarding loads, feigning sickness and purposely misunderstanding orders.

Cultural resistance

In some places, indigenous religious and cultural practices were drawn upon. For example, in the central region of Nyasaland, the secret religious groups known as nyau became the focal point for resistance to forced military labour.

Members would flee recruiters to hide in caves or graveyards connected with the group’s rituals – or hide in their own small hole in the bush, known as a machemba, and don animal masks connected with nyau. They knew that many recruiters were nyau members, that the group’s vows required members to aid each other, and that failure to do so could result in the recruiters being brough before a special nyau court.

In Dedza district – where nyau activity was especially strong during the war – the percentage of the adult male population forced into military labor service was well below the national average.

Out of Africa

Resistance to the war and recruitment also took place in the West Indies, among the Waikato tribal confederation in New Zealand and among indigenous people in the US and Canada.

Sometimes the latter were even able to find allies among the settler population. For example, on the Sarcee Reserve in Alberta, the government representative responsible for implementing federal Indian policy was so disgusted with government regulations conscripting men from the reserve that he ‘registered all eligible men only to exempt them, citing a fictitious outbreak of tuberculosis in the paperwork submitted to his superiors in Ottawa.’2

Recovering history

In 2013, launching the government’s ‘flagship programme... reveal[ing] the crucial contribution of the Commonwealth countries during the First World War’, David Cameron declared that in battlefields across the world ‘are the graves of people of all faiths and people of no faith, side by side. They fought together, they fell together, and together they defended the freedoms we enjoy today.’

Sergeant Tanko Kura was finally captured, but the following month he escaped again – this time, it seems, permanently.

In these centenary years, the government’s dishonest framing of the grotesque realities of imperial history should be a spur to all of us to try and recover the stories of those like Tanko Kura, Te Puea and countless unnamed others across the globe who resisted empire’s call.

NOTES

[1] Bill Nasson, ‘British Imperial Africa’, in Robert Gerwarth & Erez Manela (eds), Empires at War: 1911 – 1923, Oxford University Press, 2014, pp146-147.

[2] Timothy Wineguard, Indigenous Peoples of the British Dominions and the First World War, Cambridge University Press, 2011, pp153-154.