In November 1950, 52 delegates arrived in Dover, bound for the third congress of the (Communist-inspired) World Peace Council in Sheffield. All but one were denied entry.

Whether the Foreign Office considered modern art too esoteric to have much propaganda value (across the pond the CIA took a different tack, covertly promoting Abstract Expressionism as a Cold War weapon) or it was simply too embarassing to turn back the world’s most famous living artist, Picasso was admitted.

‘What can I have done that they should have let me through?’ he asked his friend Roland Penrose.

This was his second – and last – visit to Britain. In 1919, he had travelled to London to design the sets and costumes for the premiere of the ballet The Three-Cornered Hat – and this exhibition includes work from both trips, including a wonderful drawing of the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova made during the 1919 visit (perhaps wisely, she insisted that Picasso’s wife be present during the sitting), and an impromptu crayon mural of a winged man and woman, drawn on the sitting room wall of the crystallographer JD Bernal at a party after the 1950 congress (‘What’s that got to do with peace?’ one of the guests is supposed to have shouted).

However, as its title suggests, the dominant theme of the exhibition is Picasso’s influence on British artists such as Wyndham Lewis, Henry Moore and David Hockney.

Few reviewers have failed to note that such a juxtaposition does the British contingent few favours. I for one was reminded of the old Chinese proverb that ‘When a wise man points to the moon, the fool looks at the finger’, and even this art naif soon gave up looking at the finger.

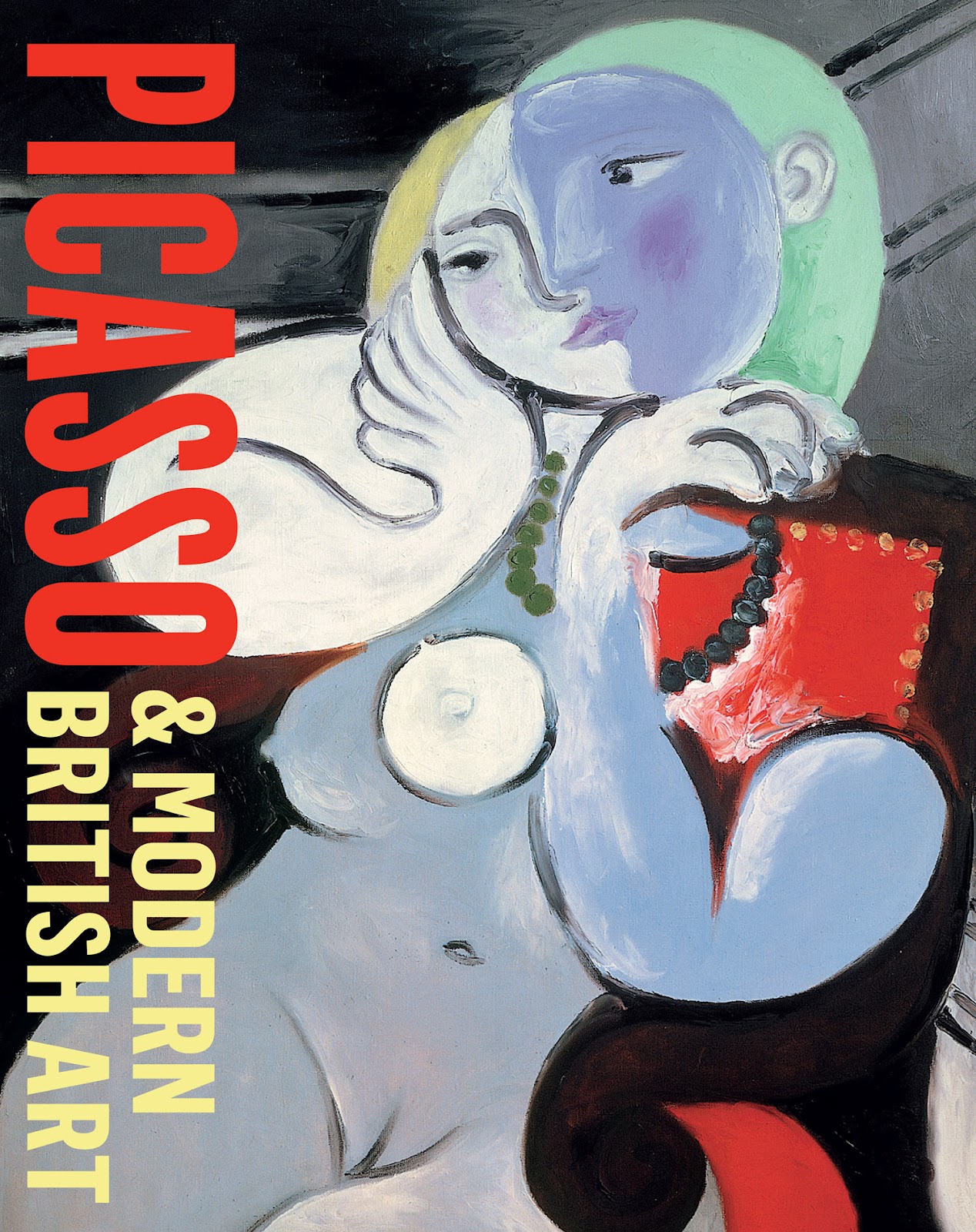

But what a moon! ‘The Frugal Meal’, ‘Nude, Green leaves and Bust’ (with its not-so-subtle nod to Man Ray’s bondage photos), ‘Minotauromachy’, ‘Women of Algiers’ (pictured) and ‘The Three Dancers’, all under one roof.

In his essay, ‘The Politics of Picasso in Cold War Britain’, which appears in the lavishly-illustrated book accompanying the exhibition, Andrew Brighton notes that the Picasso archives contain numerous letters of appeal or thanks from groups such as Amnesty, the Anti-Apartheid Movement and the National Campaign for the Abolition of Capital Punishment, and that Picasso continued to ‘give work to be used as graphics or to raise money for the causes of “intelligent” opinion in this country and internationally.’

Today, those ‘causes of “intelligent” opinion’ surely include both climate change and the arms trade. One wonders therefore what the man who told the Sheffield congress ‘I stand for life against death; I stand for peace against war’ would make of BP’s sponsorship of the Tate (see PN 2545) or Italian arms dealer Finmeccanica’s sponsorship of the National Gallery – and what he would do about it.