A long-time war correspondent with the Washington Post, Thomas E Ricks has turned his attention to the US civil rights movement.

Why?

‘The overall strategic thinking that went into the Movement, and the field tactics that flowed from that strategy’ reminded him of US military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The comparison with war-fighting is certainly interesting but it’s his focus on strategy and tactics, including recruitment, training, planning, logistics and communications, that will surely be of supreme interest to Peace News readers.

This framing follows on from the in-depth work done by Gene Sharp on strategic nonviolence and, more recently, Mark and Paul Engler’s analysis of the civil rights movement in This Is An Uprising (Bold Type Books, 2017) which, frustratingly, Ricks doesn’t acknowledge.

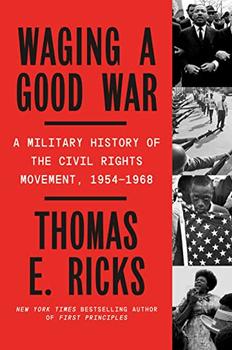

Pushing past this lapse, I found Waging A Good War to be one of the most exciting, engrossing and inspiring books I’ve read, with Ricks’s journalistic style making it very accessible (there are extensive references for those who want to dive further into the topic).

Each chapter focuses on a key action – from successes like the 1955 – 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott and the 1963 Birmingham campaign, to less-well-known defeats in Albany and Chicago.

Along the way, a number of myths about the Movement are addressed.

Martin Luther King Jr is a central figure in the narrative, of course, though his human errors and the arguments of his Movement critics are highlighted.

Ricks also does an excellent job of foregrounding others who played a leading role in the fight, including trainer Septima Clark, gay ex-Communist Bayard Rustin and extraordinary young activists like James Bevel, Diane Nash, James Forman, Bob Moses and future member of congress John Lewis.

Far from being ‘passive’, the Movement was ‘militant from the start’, exhibiting an ‘aggressive’ approach ‘that seeks conflict with the adversary’.

For example, in 1960, the Gandhian James Lawson led hundreds of activists (‘the civil rights equivalent of paratroopers,’ according to Ricks) in a successful campaign to desegregate lunch counters in Nashville.

The planning was extremely detailed, with training in the theory of nonviolence, role-playing workshops to prepare for violent responses, the scouting of targets, runners communicating with campaign headquarters, and multiple waves of activists sent out to the lunch counters (‘concentration of force’ in military terms).

While the Movement’s innovative tactics – including boycotts, pickets, sit-ins, overwhelming jails, mass meetings and the smart use of the press and emerging TV news industry – ‘was able to keep its opponents off-balance’, less radical actions were also highly valued.

‘We are on the threshold of a significant breakthrough and the greatest weapon is the mass demonstration,’ King noted in May 1963, a few months before the famous March on Washington was held.

Two years later, US president Lyndon B Johnson signalled victory when he ended a speech to congress with the Movement slogan: ‘We shall overcome’. The Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, following the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

Alongside the 14-part PBS documentary Eyes on the Prize (which Ricks cites frequently), Waging A Good War is an absolute must-read for anyone interested in the practice of strategic nonviolent struggle.