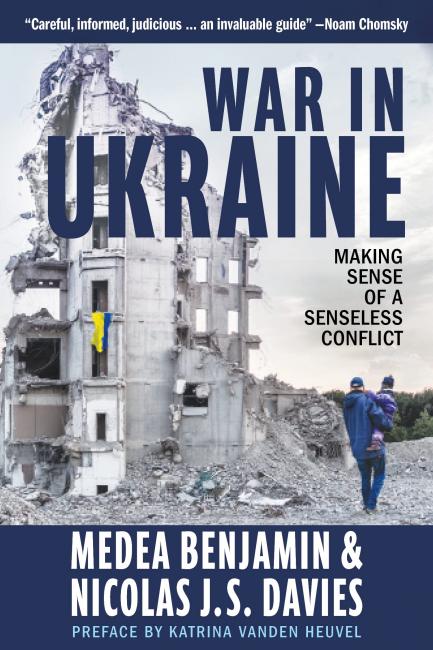

At the outset of this short book, Medea Benjamin and Nicolas Davies note that the complex nature of the conflict in Ukraine has ‘made it particularly confusing and difficult for the Western peace movement’ to respond to, with many citizens of NATO countries ‘largely oblivious to their own governments’ share of responsibility for the crisis and the carnage’.

Moreover, according to former US assistant secretary of defence Chas Freeman, the war in Ukraine is also now ‘the most intense information war humanity has ever seen. There are so many lies flying about that it’s totally impossible to perceive the truth’.

This book has been written in large part to help peace activists and concerned citizens to overcome these obstacles and ‘make sense of how the world came to this dire circumstance in 2022 and how we can move forward from here’.

It should be stated explicitly at the outset that the authors are no apologists for either Vladimir Putin or the Russian invasion.

Indeed, they describe the latter as both ‘brutal and senseless’ and ‘an illegal crime of aggression’.

At the same time, however, Benjamin and Davies note: (1) that while the war is criminal, it was also very much provoked; (2) that the current US-UK policy of attempting to use the war to ‘weaken’ Russia poses a serious danger of escalating into a nuclear war, with all the horrors that would entail; and (3) that the only other way for the war to end is through negotiations, as there is no realistic ‘military victory’ option for Ukraine.

As regular readers of PN will be aware, attempts at peace negotiations early in the war, which looked promising, were undermined by Britain (see PN 2661).

Necessarily, support for negotiations to end the war should be a central focus for the peace movement, however grim the prospects might currently look. (There have already been successful negotiations over the issues of prisoners and grain exports.)

The book’s first two chapters focus on the key events leading up to Russia’s February 2022 invasion: in particular, the Euromaidan uprising of 2014 (which ousted Ukraine’s corrupt, pro-Russian, elected president, Viktor Yanukovych) and the history of the Minsk II agreement of February 2015, which sought to end the resulting civil war in the east of Ukraine.

Begun as ‘a broad-based movement reflecting the disillusionment of pro-EU Ukrainians, who were frustrated with what they saw as Yanukovych’s broken promise to join the EU, and angry at his corruption and abuses of power’, the 2014 uprising ended as an armed revolt with significant involvement from Ukraine’s extreme right.

The authors note that ‘while the final execution of the coup against Yanukovych owed much to Ukraine’s extreme right, the actual transition of power in Kyiv was not a revolution but just “a new deal of the cards” among Ukraine’s oligarchs’.

Benjamin and Davies also lay out evidence to support their judgement that the outcome, which they correctly label a coup, was ‘strongly supported and to some degree engineered’ by the US.

By instituting a ceasefire, creating a buffer zone and deploying international ceasefire monitors, the Minsk II agreement ‘succeeded in ending the most destructive phase of the civil war’.

However, provisions that should have led to ‘decentraliing [of] power and granting Donbas a new, autonomous constitutional status’ were not carried out. The US consistently acted as a ‘spoiler’, ‘quietly incentivising and supporting… the Ukrainian government, to pursue military alternatives to the agreed upon political resolution’.

In the end, Minsk II failed ‘due to a lack of will on the part of the government in Kyiv, the anti-democratic power of the extreme right in Ukraine, and a lack of diplomatic and political support from EU countries and the United States.’

Notwithstanding promises it had made not to do so – and warnings from numerous experts that it could ultimately lead to catastrophe – NATO had been expanding towards Russia’s borders ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In 2008, William Burns (then US ambassador to Moscow, now director of the CIA) wrote to then-US secretary of state Condoleeza Rice, asserting that: ‘Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all redlines for the Russian elite (not just Putin). In more than two and a half years of conversations with key Russian players, from knuckle-draggers in the dark recesses of the Kremlin to Putin’s sharpest liberal critics, I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine in NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russian interests.’

Yet, under US president Barack Obama, following Euromaidan, ‘the US and NATO countries provided “non-lethal” military aid, trained Ukrainian forces, and conducted military exercises in Ukraine with other Eastern European countries… impact[ing] the military balance in the civil war in Donbas and undermin[ing] the Ukrainian government’s commitment to the Minsk II agreement for a peaceful, political resolution of the conflict’.

At the same time, the CIA sent small teams of special operations forces to eastern Ukraine to train Ukrainian forces in ‘sniping, sabotage, and assassination’.

When Donald Trump became US president, he rapidly lifted the ban on lethal military aid – and the far-right Azov regiment became one of the first units to receive US training on new US grenade launchers.

In 2021 (under US president Joe Biden): NATO and Ukraine conducted joint naval exercises with 30 warships and 40 warplanes in the Black Sea; 15 NATO nations took part in a joint military exercise in western Ukraine; and US defence secretary Lloyd Austin went to Kyiv and told Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy that the United States supported Ukraine’s bid for NATO membership.

Between 2014 and the end of 2021, the US provided $2.5bn in military aid to Ukraine.

‘[F]rom Russia’s perspective,’ the authors note ‘if they were going to have to fight to defend the Donbas and Crimea, every year they waited to do so would reduce their escalation dominance’. [‘Escalation dominance’ has been defined as ‘the ability to threaten or coerce other nations by being capable of dominating the next level of escalation of violence’ – ed]

In December 2021, Russia proposed two draft mutual security treaties (one between Russia and the US and the other between Russia and NATO). The US ‘refused to take Russia’s drafts as a basis for negotiation on any of the issues they raised: NATO expansion; positioning nuclear-capable weapons close to Russia’s borders; arming Ukraine; withdrawal from the INF (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces) Treaty; or even the lack of a phone hotline between Russia and NATO to defuse tensions in a nuclear emergency’.

All of which amply makes the case that the war was provoked.

This is an important point, as mainstream media coverage often makes it seem as though the Russians are acting out of pure, senseless evil, and that there are no legitimate issues to be negotiated.

Between 24 February (when Russia invaded) and 12 December 2022, the US gave Ukraine at least $19.3bn in military aid.

Despite this, propaganda aside, there is no realistic chance of Ukraine defeating Russia militarily.

By prolonging the war and opposing real peace negotiations, the US and Britain are increasing the possibility that Russia will ultimately resort to using its one trump card: nuclear weapons.

Indeed, in June 2022, the director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) warned that ‘the risk of nuclear weapons being used seems higher now than at any time since the height of the Cold War’.

In her recent PN talk Benjamin quoted John F Kennedy’s crucial 1963 warning that ‘nuclear powers must avert those confrontations which bring an adversary to a choice of either a humiliating retreat or a nuclear war’.

Assuming a nuclear war is avoided, Benjamin and Davies point out that the war ‘must sooner or later end at the negotiating table’.

They recap the Istanbul Ten Point Plan of March 2022 – which looked like it might have been able to end the war at an early stage – as well as Boris Johnson’s surprise visit to Kyiv in April, where (according to Ukrainian media) he told Zelenskyy ‘to stop talking to the Russians and concentrate on defeating them militarily’.

Other topics briefly explored include propaganda from all sides (NATO, Ukraine and Russia), opposition to the war inside Russia, and the consequences of western sanctions (both for ordinary Russians and people across the world).

PN readers will already be familiar with some of the material (on negotiations, nuclear threats and so on) but may be less so with respect to the long sequence of events that paved the way for the invasion.

Brief, judicious and well-written, this is an excellent primer for western peace activists or anyone else concerned about ending the carnage in Ukraine.