Dear readers, I’ve belatedly made the acquaintance of a remarkable US writer who died a month after I was born. I wish I’d encountered him years back but here’s a quote and you’ll see why he immediately endeared himself to me: ‘When a man tells you that he got rich through hard work, ask him: “Whose?”’

Don Marquis, novelist, poet, newspaper columnist, playwright and (I insist) philosopher, was born in 1878 and in 1916 he began a famous column in New York’s The Evening Sun (later The Sun) which introduced readers to his remarkable creations, archy and mehitabel, who gave rise to his most successful and enduring books.

Now get this: archy is a cockroach into whose body has transmigrated a free verse poet – or vers libre poet, as archy insists. His friend and sometimes opponent, mehitabel, is an alley cat with aristocratic as well as bohemian leanings; her motto is toujours gai (‘always gay – forever happy’). In her previous incarnation, as she persistently broadcasts, she was Cleopatra. Grabbed? Well you should be.

Another US journalist, essayist, and revered children’s author from this time was a friend and admirer, EB White, who said of Marquis’ work: ‘it is bold, disrespectful, full of sad beauty, bawdy adventure, political wisdom, and wild surmise’. I can only say amen to that.

I would add, however, that Marquis reads like an instinctive anarchist and pacifist to me. The wise and witty debate which continually occupies archy and mehitabel throughout their barbed relationship picks away at the warlike and blinkered behaviour of humankind (well menkind actually) and arouses both fury and resignation in archy. He is forever pacific, however, while the proto-feminist mehitabel is given to appallingly funny acts of violence against tomcats.

But to explain this surreal relationship you need to know how it works; it is archy who’s typing the words and he achieves this by banging his forehead on the keys. Operating the shift is beyond him, of course, and this explains why his work is entirely in lower case and devoid of punctuation. He works at night and leaves his copy in the typewriter for its owner (addressed as ‘boss’) to read in the morning.

Very occasionally, the boss interjects with a comment of his own but archy’s account of his own life and his biography of mehitabel are what might be described as stream of consciousness but are actually a series of very clever vers libre poems. The archy and mehitabel exchanges were first published in 1927 and have never been out of print since.

There’s even a continuous but never boring literary debate which sets vers libre against traditional literary forms. Sometimes archy revolts against free verse and writes in rhyme but whichever method he uses the result is beautifully-turned, effortless poetry which often looks like the work of the US poet e e cummings (born 1894) who was famous for eschewing capital letters and punctuation.

In fact, the literary debate broadens into endless speculation by archy and mehitabel about their human forms hidden somewhere within themselves and they habitually contrast the foolishness and bigotry of humans with the superior intelligence of animals, insects, and fishes. Here’s a taster from the archy and mehitabel omnibus (Faber and Faber, 1998):

as far as government is concerned

men after thousands of years practice

are not as well organised socially

as the average ant hill or beehive

they cannot build dwellings

as beautiful as a spiders web

and I never saw a city

full of men manage to be as happy

as a congregation of mosquitoes

who have discovered a fat man

on a camping trip

I’ve enjoyed every mordant word of this book and identify absolutely with archy’s inveighing against menkind’s obsession with, and faith in, warfare.

Let’s not end on this note, however. Here’s the triumphant mehitabel striking back against the forces of conformity in her own inimitable way:

artists who live in

their studio

in the greenwich

village section

of new york city

have taken pity

on her destitution

and have adopted

her this is the

life archy she says

i am living on

condensed milk and

synthetic gin hoopla

for the vie de boheme

exclamation point

Topics: Culture

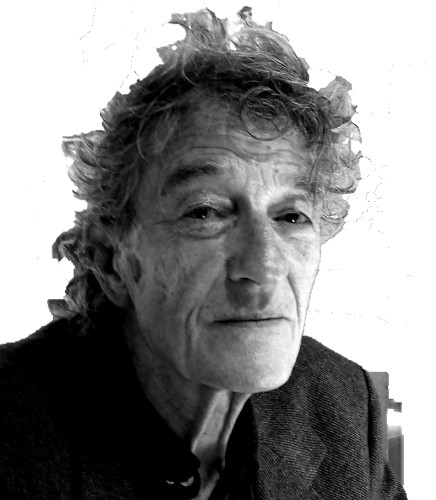

See more of: Jeff Cloves