While ‘[m]any people believe that America’s addiction to automobiles is a cultural problem’, in reality – as cartoonist Andy Singer explains in this wonderful ‘pictographic examination’ of the American transport system – the country’s ‘automobile addiction has more to do with politics, government agencies, and the [US] tax structure’.

While ‘[m]any people believe that America’s addiction to automobiles is a cultural problem’, in reality – as cartoonist Andy Singer explains in this wonderful ‘pictographic examination’ of the American transport system – the country’s ‘automobile addiction has more to do with politics, government agencies, and the [US] tax structure’.

Indeed, in the 1920s, most North Americans lived in cities, many of which had great public transit and inter-urban rail systems, leading the president of General Motors, Alfred Sloan, to note that – as the flattening demand for cars led to a change ‘from easy selling to hard selling’ – it would be necessary to ‘reorder society ... to alter the environment in which automobiles are sold’, by either eliminating these systems or converting them to buses.

Joining forces with Standard Oil of California, Firestone, Mac Truck and Philips Petroleum, GM created a front company – National City Lines – that bought up and dismantled over 100 rail transit systems in more than 45 US cities. GM and its partnters were later convicted of conspiracy but received only a slap on the wrist: each company was fined a mere $5,000.

Of course, more cars need more roads, and the second major factor – the creation of modern government ‘agencies’ in the 1920s and ‘30s – was to produce a ‘highway industrial complex’ that would supply them.

Indeed, ‘[b]y the mid-1950s, highway agencies had managed to get exclusive control of billions of dollars in federal and state gas taxes’, becoming one of the most powerful forces in state politics, with a strong institutional imperative to grow larger and more powerful by building more and more road projects.

Many of the negative impacts of the resulting car culture should be familiar: road deaths, raised levels of obesity, pollution, global warming and the creation of an oil-dependent transport system that has become enmeshed with an aggressive foreign policy (incredibly, roughly one out of every seven barrels of oil extracted from the ground is now burned on America’s roads).

However, the number one problem posed by cars, Singer argues, is that they waste so much physical space, promoting low-density, sprawling development that reduces human interaction and that then ‘requires more fuel, land, resources and time to transport people to and from employment and essential services’.

So what is to be done?

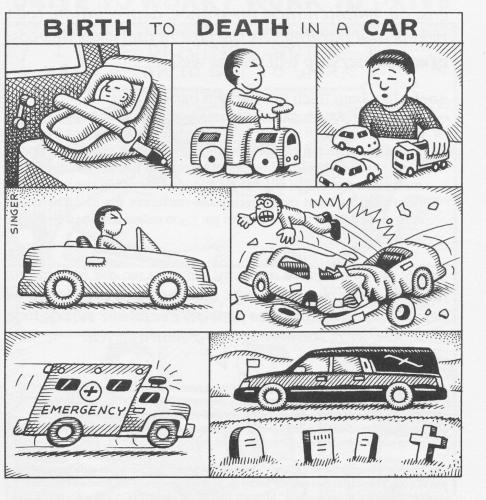

Noting that ‘sometimes, not burning hydrocarbons or going anywhere is the most radical thing you can do’, Singer recommends living without a car (cycling from his wedding ceremony to the reception really made him appreciate ‘how the wedding and funeral industries have managed to make automobile processions a part of our sacred rituals’), getting involved with pro-cycling events such as Critical Mass bike rides, and the creation of a large car-free section of an American city as a inspirational model for others.

Noting that ‘sometimes, not burning hydrocarbons or going anywhere is the most radical thing you can do’, Singer recommends living without a car (cycling from his wedding ceremony to the reception really made him appreciate ‘how the wedding and funeral industries have managed to make automobile processions a part of our sacred rituals’), getting involved with pro-cycling events such as Critical Mass bike rides, and the creation of a large car-free section of an American city as a inspirational model for others.

But he is also clear that ‘[there is no substitute for making major legislative changes’, for example amending state constitutions to allow state gas taxes to be spent on public transport or non-automotive transportation, and – ultimately – diverting all tolls and gas tax dollars, except those needed for basic road maintenance, into public transport and urban revitalisation.

There have already been some successes. For example, in 2002, when the Virginia department of transport tried to pass a sales tax to finance widening a beltway around Washington DC, a massive grassroots campaign was able to win a referendum on the issue in the affected counties (though the scheme has now risen, zombie-like, from the grave).

Short and stylishly-illustrated, with a useful bibiography and directory of campaigning organisations, Singer’s book will be useful reading for all transport activists based in the UK – where, despite there being no technical, financial or organisational obstacles to making our land transport system zero-carbon by 2050, Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, instead wants to spend £18bn on hundreds of new road projects across the UK.

However, it would be nice to have a similarly pithy volume outlining the political history of our own transport system.

Any volunteers?