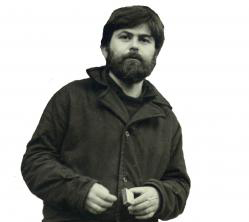

There are not so many anarchist pacifist poets in print that we can afford to overlook any one of them. In John Rety’s case he was – what ever else – a hard man to overlook or ignore. He was by nature a (nonviolent) combatant and faced with an empty room he’d have had an argument with himself. A cliché, I know but its truth suited him to the ground. So, this posthumous collection of new and selected poems is a welcome arrival and worthy of attention.

There are not so many anarchist pacifist poets in print that we can afford to overlook any one of them. In John Rety’s case he was – what ever else – a hard man to overlook or ignore. He was by nature a (nonviolent) combatant and faced with an empty room he’d have had an argument with himself. A cliché, I know but its truth suited him to the ground. So, this posthumous collection of new and selected poems is a welcome arrival and worthy of attention.

Advertisement

I need an enemy

Everyone else has an enemy

Why haven’t I got one?

Would you like to be my enemy,

If so send CV –

I am an equal opportunities employer

Apply in confidence

I met John rarely, so he was an acquaintance rather than an intimate so, before getting to his poems, a word or two about the publisher’s preface by Martin Parker, the foreword by his friend, Stephen Watts, and the afterword by his dear daughter, Emily Johns. These are splendid pieces of their kind and told me many things I didn’t know about John. In every way they are aids to understanding his work and are doubly valuable for that reason. Some of what Emily has to say was revealed in Milan Rai’s obit of John in March 2010 (PN 2519) but, importantly, she reveals that he was fundamentally insecure about being stateless. He finally became a British cit in 2007: ‘Again and again through his poems there is the refrain of displacement. his aunt burned his [Hungarian] passport and there was no way back.’ He was in exile for the rest of his life.

Even without this knowledge it’s impossible not to recognise this displacement and it gives cohesive strength and (often angry) loss to his work, which he aids by compression. He can say a lot in very few words and, to my taste, his shortest poems are invariably his best. Emily also tells of: ‘the awful impact on his childhood of the war and the siege of Budapest.’

World War Two

My mother wore a paper shirt

My father wore a hat –

The metal albatrosses

Soon put a stop to that.

I see them faintly smiling still

And a bit surprised at that

For mother sweet was fond of her shirt

While father was at one with his hat.

But fate and destiny jointly declared

An unequal war on my mother’s shirt

And their metal albatrosses

Destroyed my father’s fine hat.

Sometimes there’s an odd un-Englishness about John’s phrasing which reminds you he’s a continental European. I like this and I like the way he often sounds – he has similar wit and brevity – like Jacques Prévert the French pacifist poet and screenwriter.

That was that

He went out for a cigarette

And came back without his hat

He went out to look for his hat

And came back without his cigarette.

For a man who wasn’t short of bombast there is an engaging modesty about John’s life and work. He was often loud but not loud-mouthed about the poetry by others he published in his imprint Hearing Eye. About his own poetry he was modest but ironically aware of his worth I feel:

The poet offers his wares

I have four liners

I have four liners

I have four liners

I have four liners

Also have three liners

Also have three liners

Also have three liners

Plenty of two liners

Plenty of two liners

Working on one liner now

The above poem is clever and witty but there’s more to it than that. John had no religion and though he found the world absurd he somehow reached an accommodation:

However absurd

Every moment is different

All we can hope for

Is that as each moment changes

However absurd we should still understand

Each moment’s meaning

Pleasing or unpleasing.

There are lovely poems dedicated to his companion Susan Johns and their daughter Emily in which loss and love and war entangle, but the loss of his parents in particular lurks by inference or sometimes directly in his work:

Address unknown

Mother they are killing each other,

Death is everywhere.

The language you taught me

It’s useless, mother, their bombs

Have made me deaf.

And I live among the living dead.

Otherwise, everything is alright

And I have some wonderful friends

But it looks to me

Something might be done about

The state of the world

Both in his life and his work John tried to do something about the state of the world.

That is what the best poets have always done and do.

He’s in good company.

Vision at 12.30am

From Baker Street to Euston Square

On a rattling hurtling tube train

Early morning very weary

The dirty dozen travelled together

On their way to who knows where

Very weary, very wary

Early morning tempers all

Blackman, hippy, gay and pleasant

On their way to who knows where

Hurtling through the empty stations

confident and fair.

I smiled, he nodded, she twinkled

He nodded, she twinkled, I smiled

From Baker Street to Euston Square

On a rattling hurtling tube train

Early morning very weary

On our way to who knows where

Just as cheerful, just as fair and how

We laughed and smirked and twinkled

(the new jews)

On the last train to Dachau.