Peace News: How did your early life shape your worldview, and your activism?

Peter Tatchell: I grew up in a conservative, working-class family in Melbourne, Australia, in the 1950s, ’60s. My parents were devout evangelical Christians, with no interest in social issues.

My mother remarried when I was six. I suffered a lot of violence at the hands of my stepfather; even forcing me to work long hours in his backyard farm. My mother could not leave him; there were no refuges or welfare support.

Simultaneously, my mother suffered from life-threatening asthma. With no NHS, much of our limited income went on medical bills. I remember thinking how unfair it was that we should suffer extreme poverty on account of illness.

These early hardships gave me a burning dislike of injustice.

In 1963, news broke of the racist bombing of a black church in Birmingham, Alabama, murdering four young girls. It began my support for the Black Civil Rights Movement.

When I began my activism aged 15, I took my inspiration from, and modelled my methods on, the work of Martin Luther King – and Mohandas Gandhi.

Nonviolent direct action (NVDA) and civil disobedience have been at the core of my activism.

Gandhi and Martin Luther King proved NVDA can be a means of liberation for the marginalised and despised.

My earliest campaigns were for indigenous Aboriginal rights and against the death penalty, apartheid, the draft and Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

I refused to participate in an unjust, immoral war. Facing two years jail if I refused to register for military service, I skipped the country and came to London.

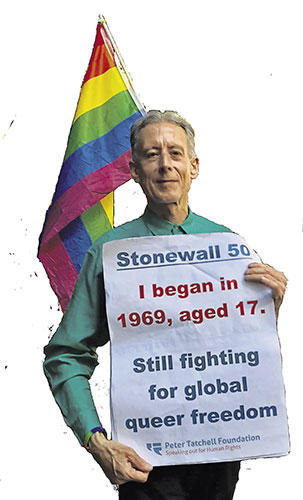

PN: How have you sustained your passion and motivation for activism for 54 years?

PT: I’m a child of the 1960s, an era of idealism and optimism. I’ve always believed that social change is possible and have participated in many social victories, from defeating the Poll Tax to securing LGBT+ equality.

I worked in solidarity with movements that overthrew Franco and Pinochet and with those who won independence for former colonies like Zimbabwe and Mozambique.

Bruce Kent and I co-ordinated a public appeal to service personnel to refuse to obey nuclear orders, arguing that they were contrary to the international laws of war. We distributed leaflets outside military bases in a deliberate challenge to the government’s nuclear war planning.

I estimate I’ve helped about 20,000 individuals and campaigners over five decades.

These successes have been great motivators, spurring me on to do more and enabling me to cope with astronomical levels of hate and violence.

PN: What does self care for activists look like to you? How did you cope during the 1983 Bermondsey by-election – and during the HIV/AIDS epidemic?

PT: I’ve participated in over 3,000 protests and 100 arrests, been violently assaulted more than 300 times and endured 50 attacks on my flat, including bricks through the windows, three arson attempts and a bullet through my letterbox.

Half of these assaults occurred during the [Bermondsey] by-election – when I stood as a left-wing Labour candidate advocating LGBT+ rights and nuclear disarmament – causing post-traumatic stress disorder.

It was only bloody-minded determination and my supportive friends that got me through.

“I’ve been violently assaulted more than 300 times and endured 50 attacks on my flat, including three arson attempts.”

The HIV pandemic was incredibly stressful, with gay men being vilified as carriers of the ‘gay plague.’ Over a dozen people I knew died of AIDS. It was like living through a war.

Gay men of my generation are burdened with that collective trauma.

PN: The candlelit vigil for HIV/AIDS was incredibly moving. Can you tell us how it came about?

PT: In the mid-1980s, people with HIV were being demonised by tabloids, religious fanatics and right-wing MPs.

I co-drafted the world’s first AIDS Human Rights Charter, together with Phil Cox, a gay man living with HIV. When we heard that a World Health Ministers Summit on AIDS was scheduled to be held in London in January 1988, we decided to organise a huge candlelit vigil.

PN: Regarding taking direct action in Russia, did you ever consider tactics that would put you in less physical danger?

PT: I knew other tactics would be safer – but less effective. I wanted to do an impactful protest that would highlight Putin’s homophobic regime.

My gamble was that my British passport would give me protection and that the Russians would be keen to avoid bad publicity during the [football] World Cup.

PN: How did it feel to hear the former archbishop of Canterbury say that you have been a figure for good and are on the right side of history?

PT: It was surprising and generous.

I don’t believe ‘once an enemy, always an enemy’. I challenge bigots and tyrants, but my goal is to turn enemies into friends.

PN: Will you ever let your health stop you participating in direct action?

PT: I intend to keep protesting – probably well into my 90s. There are still so many injustices.

I think of activists in Russia and Iran who keep going despite risks to their lives and liberty. Their courage inspires and motivates me.

PN: What is your attitude to NVDA as a method of social change? Does it boil down to the type of opponent you’re facing?

PT: Despite the flaws of Western democracies, violent tactics are never justified while opportunity for peaceful change exists.

Political violence is counter-productive: instead of examining the cause, everyone focuses on the violence.

I support a united Ireland, but IRA violence alienated public opinion. The nonviolent methods of the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association were far more effective.

My default position is pacifism.

I can only support war as a last resort and self-defence, when people are in danger of massacre and there is no other practical option.

I think it was right to resist the Nazis and ISIS militarily, to prevent far greater suffering.

While Danish people demonstrated the power of nonviolent passive resistance during the Second World War, the Nazis could not have been defeated by NVDA alone.

I reluctantly support ‘Just War Theory’.

PN: Why do we still need Pride in the UK?

PT: There are still battles to fight. A fifth of the public believe homosexuality is wrong, half of LGBT+ pupils have been bullied and a third of LGBT+ people have been hate crime victims.

The government hasn’t banned LGBT+ conversion therapy or reformed the Gender Recognition Act to allow trans self-ID.

Pride parades have become commercial and depoliticised. That’s why there will be a ‘Reclaim Pride’ march on 24 July, at 1pm in Parliament Square. Unlike existing Prides, we will put LGBT+ human rights demands front and centre.

PN: Finally, when was the first time you realised you’d made a concrete difference, and how did that feel?

PT: When I was 15, I heard that a lack of education/qualifications was one factor in why indigenous Aboriginal communities were so impoverished.

I helped organise a sponsored walk to fund scholarships for indigenous pupils. The scheme that I contributed to still exists. I was glad that we helped fund indigenous peoples’ acquiring the skills to empower themselves.