Renewable energy is ‘already more than capable of scaling up at the speed necessary to protect the climate, meet energy demands, ensure energy access for the poor, and support sustainable development’, according to Fossil Fuel Exit Strategy, a June 2021 report from the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS).

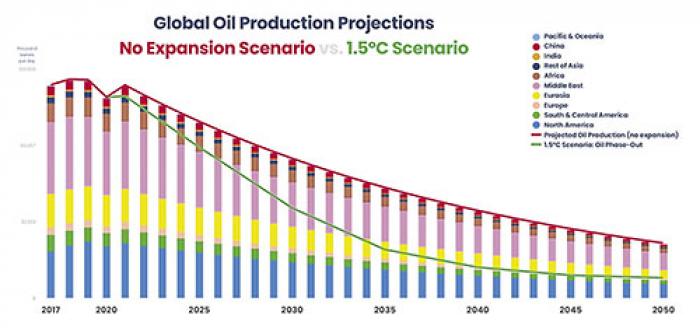

The problem is that, even if we stop fossil fuel expansion immediately, ‘with just the fossil fuels to be extracted from existing projects alone’, the UTS report warns, the world will still ‘massively overshoot’ the goal of limiting average global temperature rises to 1.5 °C.

Avoiding catastrophic climate change doesn’t just mean an end to exploration and expansion of fossil fuel production, it also requires ‘an active phase down of existing projects’.

The good news is that the biggest economic disruption of our modern era – the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy – is now well and truly under way.

The main obstacles to avoiding catastrophic climate change are now political rather than technological or economic.

It’s now possible to capture – with current technology (and excluding mountains, cities,forests, and areas that are too far from where people live) – at least 6,700 PWh of energy every year from solar and wind. That is more than 100 times current global energy demand.

This estimate comes from an April 2021 report from the respected independent thinktank, Carbon Tracker.

(If you boiled your kettle 10 times, it might use up one kilowatt-hour [kWh] of energy. A PWh is 1,000,000,000,000 kWh.)

There has been a stunning collapse in the cost of renewable power over the last three years.

This means that more than half of this technologically possible solar and wind power now has economic potential as well.

By the end of the decade, over 90 percent of Carbon Tracker’s 6,700 PWh solar/wind energy will be economically feasible.

In fact, solar or wind are already the cheapest sources of new bulk electricity production for 75 percent of the world’s population.

Land is not a constraint. The land required for solar panels to provide all global energy is only 0.3 percent of the global land area – probably less than the land required for fossil fuels today.

The only real question is whether the transition to renewables will take place fast enough – and if fossil fuels will be phased out quickly enough – to limit global warming to 1.5 °C.

This is a political question, not a technological one.

‘A decisive moment’

In May, the International Energy Agency confirmed in a major report that ‘there can be no new investments in oil, gas and coal, from now – from this year’ if the world is going to limit global warming to 1.5 °C. The IEA has long been closely aligned with fossil fuel interests.

The IEA’s executive director, Fatih Birol, wrote that the ‘gap between rhetoric and action [now] needs to close if we are to have a fighting chance of reaching net zero by 2050 and limiting the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 °C.’

He stated: ‘We are approaching a decisive moment for international efforts to tackle the climate crisis’.

The trouble is that the IEA report actually understated the current challenge. Its ‘roadmap’ for limiting global warming to 1.5 °C relies on unproven technologies to capture the emissions from burning fossil fuels and to suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

If you don’t assume that such technologies will appear, then even the existing reserves of fossil fuels are enough to bust 1.5 °C.

The UTS report we started with states that: ‘to remain aligned with a 1.5°C trajectory, global fossil fuel production will need to decline by an average of 9.5% for coal, 8.5% for oil and 3.5% for gas per year between 2021 and 2030’.

In contrast to the IEA roadmap, the UTS report explains a way we can hold to a 1.5 °C rise while limiting our reliance on ‘unproven technology and unrealistic levels of land use’.

The UTS report has a number of other features that PN readers may find attractive. It ‘assumes a phase-out of nuclear energy’, makes ‘minimal reliance on hydropower beyond existing capacity’ and assumes that biomass (that is, animal or plant material burned as fuel) ‘is sourced primarily from cascading residue use and wastes’.

"With just the fossil fuels from existing projects, the world will ‘massively overshoot’ 1.5 °C."

The report recognises that using harvested forest products such as wood pellets for bioenergy is ‘not carbon neutral in the majority of circumstances’.

Moreover, in the UTS plan, any fossil fuels remaining in 2050 ‘will only be used for non-energy uses such as the petrochemicals industry’.

In contrast, the IEA’s ‘Net Zero’ pathway still has fossil fuels contributing 20 percent of global energy supply in 2050.

The barrier

The path outlined in the UTS report would produce ‘millions of new jobs, reduce annual air pollution deaths, stabilise global energy prices and provide annual savings in health and climate costs.’

The world is heading fast in the opposite direction.

In 2019, the oil and gas industries were forecast to spend $4.9 trillion over the next decade on new oil and gas fields – none of which is compatible with limiting warming to 1.5 °C.

Without a seismic change, the world will be producing 120 percent more fossil fuels in 2030 than would be consistent with a 1.5 °C pathway.

Why is this happening?

As the Carbon Tracker report explains: ‘the main remaining barrier to change is the ability of incumbents [that is the fossil fuel companies and their allies] to manipulate political forces to stop change.’

In the first three years after the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, the five largest publicly-traded oil and gas companies (ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, BP and Total) invested over $1bn of shareholder funds ‘on misleading climate-related branding and lobbying’.

That’s according to a March 2019 report by another respected climate thinktank, InfluenceMap.

InfluenceMap comments that these branding and lobbying efforts have been ‘overwhelmingly in conflict with the goals of this landmark global climate accord’, the Paris Climate Agreement. They’ve been ‘designed to maintain the social and legal license to operate and expand fossil fuel operations’.

By the way, the Paris Agreement itself does not mention the words ‘coal’, ‘oil’, ‘gas’ or ‘fossil fuels’.

No time to lose

As the UTS report makes clear, a safer, more prosperous world is now possible. But it won’t happen by itself.

Urgent action is needed to undermine the still-powerful fossil fuel lobby and to create the international mechanisms necessary to rapidly phase out existing fossil fuel production.

There’s not a moment to lose.