‘This is a war story.’

‘This is a war story.’

Thus begins Nick Estes’ historical recounting of the survival of – and the resistance waged by – Native American people, the ‘first sovereigns’ of – and the ‘oldest political authority’ in – America.

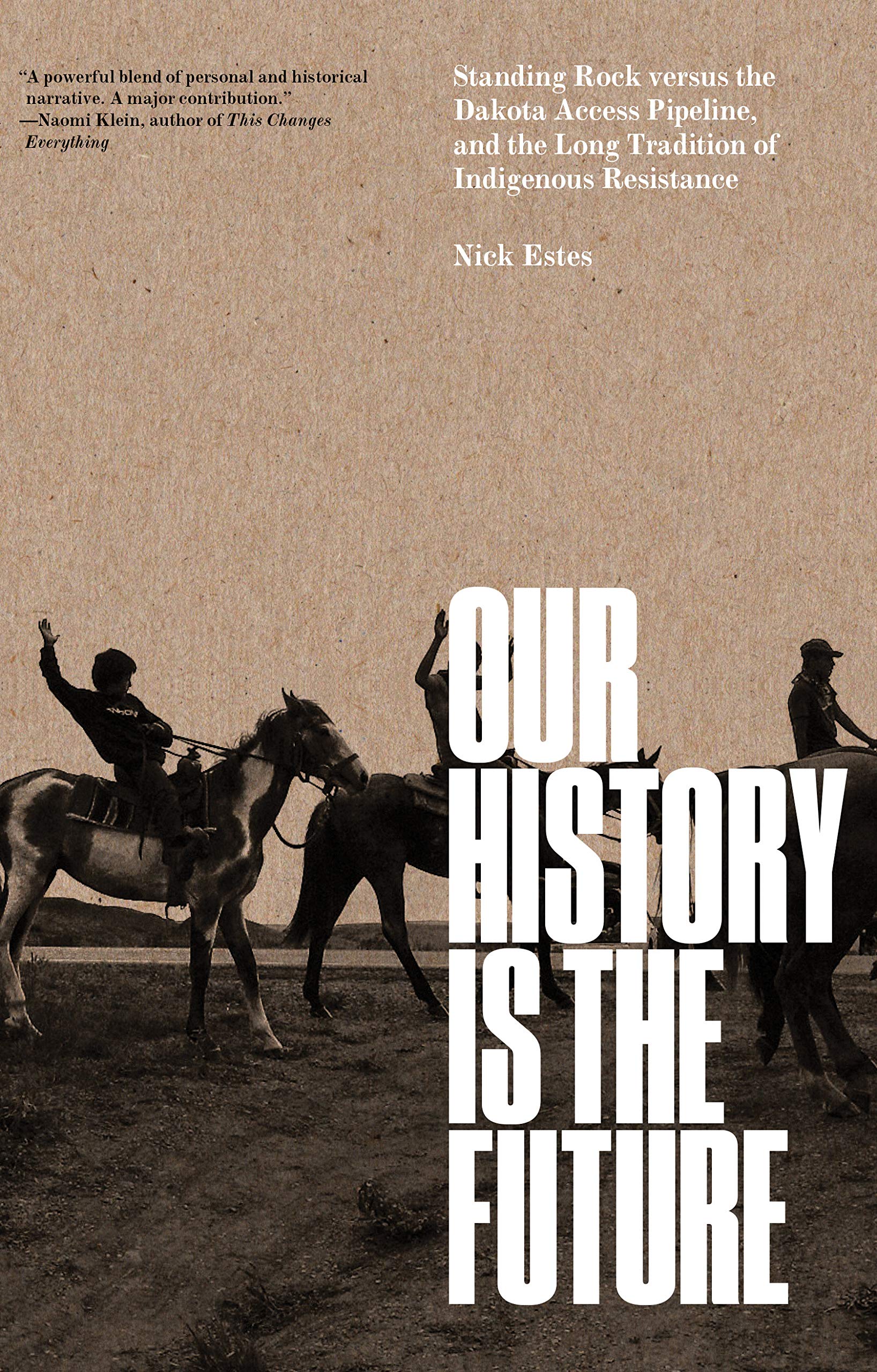

US history saw the first white settlers attempt to ‘permanently and completely replace Natives with a settler population’. This is a war that continues to rage to this day, as seen in the horrific police violence against Native Americans fighting to resist the contruction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. DAPL is a 1,172-mile oil pipeline that was built across the Sioux territory of Standing Rock.

This book is far more than a simple record of Indigenous history though. Its fluid and evocative style comes from the tradition of oral story-telling itself. Indeed, the book’s very shape is the result of a collective process, of multiple stories passed down to Nick Estes (a process he explicitly acknowledges at the end of the book.)

In the first chapter (‘Siege’), Estes skilfully takes us back to 2016 and the resistance movement against DAPL.

The decision, made in 2014, that DAPL should be rerouted from North Dakota’s white-dominated capital to upriver of the poorest part of North Dakota, the Standing Rock Reservation, clearly shows modern forms of imperialism still at play.

Not only did DAPL directly threaten Indigenous people’s homeland and drinking water, but it also posed a grave environmental threat in relation to climate change, providing a route for the transportation of hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil daily from the fields of the Bakken formation in northwest North Dakota. As Estes notes, this shows how ‘the colonised and racialised poor are still burdened with the most harmful effects of capitalism’.

To understand how much land and water are an integral part of the identity of the Oceti Sakowin (the proper name for the people commonly known as the Sioux) is also to understand the power of their resistance.

In the face of a new oil pipeline or dam project, Mní Wičóni (‘Water is Life’) trumps the sacredness of American private property. As opposed to seeing land or water as something to be used and profited from, they see themselves as part of those very elements. Their land is their past (where their ancestors are buried), present and future (for their children and grandchildren).

By taking away land and water, you are taking away the future.

As Estes so beautifully explains, ultimately it was native people’s bodies that became the sole protector of the earth: only by removing their bodies from beneath and on top of the soil was the US state able to eliminate these people’s rightful relation with the land.

The resistance centred around Standing Rock’s main camp, which Estes describes as a fully functional city: from full-time schools and kitchens to legal training and prayer actions. Estes also underlines the important role that women and Two-Spirit people (an umbrella term for Indigenous people who identify as LGBTQAI+) had in leadership positions.

But the present struggle cannot be understood without the past. Subsequent chapters (‘Origins’ and ‘War’) describe the military tactics used by white settlers on Native populations historically.

‘Flood’ tells stories of the seizing of Indigenous land (and the relocation of its people) through the construction of large public dams and of the American Indian Movement (AIM), the militant Native American advocacy group that sprang up in the 1960s.

Throughout, Estes underlines how present Indigenous revolutionaries are simultaneously ‘the ancestors from the before’ and ‘the already forthcoming’.

As opposed to seeing history as a thing of the past, the strength of their resistance is to draw on the history of their people and to evoke what’s at stake in the future.

In the tradition of Sioux activism, ‘each struggle has adopted essential features of previous traditions of Indigenous resistance while creating new tactics and visions to address the present reality and consequently projecting Indigenous liberation into the future‘.

This book is a must-read for anyone interested in the #NoDAPL movement. It works as an introduction – and a fearless analysis of – one of the biggest social movements of our times. It is also an inspiring read for anyone committed to social justice. As Estes underlines, the ‘ancestors of Indigenous resistance didn’t merely fight against settler colonials; they fought for Indigenous life and just relations with humans and nonhuman relatives and with the earth.’

This tradition of justice is all the more alive in Indigenous activism today through the figure of the Water Protectors (the name taken by the Native American resisters at Standing Rock) who ‘force some to confront their own unbelonging to the land and water.’ In the face of rampant capitalism and irreversible climate change, their resistance is a lesson and inspiration for us all.