Are you a lone wolf, a mobiliser or an organiser? And does it make any difference to how much social change you make? I’ve been chewing over questions like this after attending two very different movement events in the last few weeks.

The first was ‘Can we unite for peace?’, a conference in London put on by ‘Uniting for Peace’ on 10 March. There were many thought-provoking contributions.

Susan Tamondong of the International Development Evaluation Association told us how she got an Oxford college for international students to stop housing people in nationality/language groups, and to offer more varied food.

She got students to share food with each other from their different countries. People started connecting.

Susan helped to create unity in diversity, transforming the atmosphere.

Digging deeper

What do we mean by the question ‘can we unite for peace?’ Does ‘we’ mean groups who see themselves as part of the British peace/anti-war movement? Or is it wider?

By ‘peace’, do we mean ‘no shootings or bombings’? Or do we mean ‘restructuring society and the economy so that poor and oppressed communities gain confidence, power and economic resources and breaking down concentrations of wealth and power’? Or do we mean something else?

And what do we mean by ‘uniting’? At the conference, Lindsey German of Stop the War suggested a unity of demands that ‘we’ might make. Keith Best of the World Federalists offered examples of unity in action, when groups have formed coalitions with a common goal. Author Clive Wilson led us in an exercise to develop unity of vision.

Come together

Different kinds of questions about ‘uniting for peace’ came up at an ‘Organising for Change’ training over the 16–18 March weekend.

The workshop, co-hosted by Quaker training network Turning the Tide, was about strengthening our campaigns for peace and justice by bringing in community organising techniques and approaches.

Organising for Change is inspired, in part, by the work of Hahrie Han, a Korean-American academic. In her 2014 book, How Organizations Develop Activists: Civic Associations and Leadership in the 21st Century, Han studied the local branches of two large NGOs in the US. Why were some branches bursting with volunteers while others were barely scraping by?

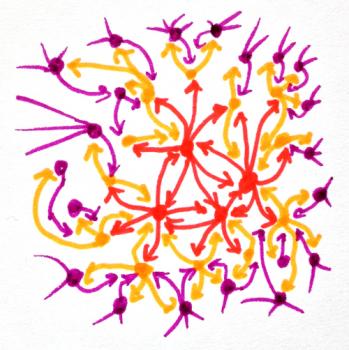

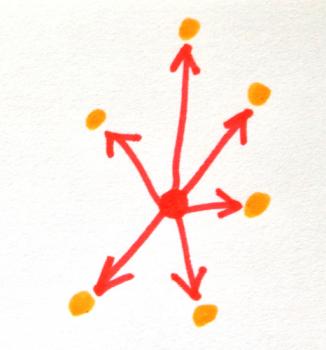

Han identified three different ways that campaigners operated. Lone wolves work on their own, often with a lot of knowledge. Mobilisers get the largest number of people possible to take action, usually by asking them to do small, easy-to-do things. Organisers don’t just ask as many people as possible to take a series of one-off actions, they choose some people to form relationships with, ask them to take on responsibilities (perhaps small at first), and give them the help they need to develop as leaders in their own right.

Han gives the example of ‘Phil’ in ‘People for the Environment’.

Phil was a volunteer leader for a certain area of his state. He divided it into three sections. He kept talking to people until he found one person in each region who was willing to take on being the local organiser.

Phil trained those three as he had been trained, and checked in with them every week.

The four of them started talking about holding a regional conference (without any funding). The three locals were the steering committee, Phil saw himself as supporting them.

The three recruited eight friends who they thought would be good to run subcommittees (such as content, media, fundraising) that they thought would be needed. Those eight joined the steering committee.

Those eight chairs were responsible for recruiting the members of their subcommittees. Phil told Han: ‘Pretty soon, we had an active group of about 100 people working on developing this conference.’

When you work this way, you not only get people involved in your campaign, you also help those people to grow their own power and therefore the power of the campaign.

What Hahrie Han found was that groups were healthier and more powerful when they blended together mobilising and organising approaches.

So, during the weekend with Organising for Change, we learned some of the tools which are useful for an organising (as opposed to a mobilising) approach to campaigning, and we thought about how to help our groups (including NGOs) and movements move over to more of an organising way of doing things.

In other words, ‘uniting for peace’ can be done in a superficial, centralised, mobilising way, or it can be done in a more relationship-based, give-others-responsibility-and-power organising way.

For example, if the students in Susan Tamondong’s college were faced with, say, unreasonable rent increases, would they be equally likely to fight and win if they were culturally and geographically divided (pre-Susan), or if they felt united in their cultural diversity (post-Susan)?

Organising is not just about prioritising strong relationships. Organising is, in Han’s words, about being ‘transformational’, giving people opportunities to change, to increase their skills and confidence and their own sense of power, so they become leaders in their own right, ready to empower others.