‘If the choice for Russia is fighting a losing war, and losing badly and Putin falling, or some kind of nuclear demonstration, I wouldn’t bet that they wouldn’t go for the nuclear demonstration.’ That was Tony Brenton, a former UK ambassador to Russia, talking to Reuters in August.

Western experts have explained some of the ‘demonstration’ options for Putin, if he does use nuclear weapons in Ukraine, detonating a single ‘low-yield’ warhead in a way that does not kill anyone: ‘It could be a detonation underground, over the Black Sea, perhaps somewhere high in the skies above Ukraine or on an uninhabited site such as Snake Island.’ That’s how the Financial Times summed it up.

The ‘high above Ukraine’ explosion would create an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) that would knock out electronic equipment as a side-effect.

Alternatively, suggest the experts, Putin could strike Ukrainian military forces as they gather for an offensive; a Ukrainian military base; critical infrastructure; or an actual inhabited city (the Hiroshima option).

Professor Lawrence Freedman, one of Britain’s most respected military analysts, has suggested that Putin might start with a nuclear demonstration on a remote area, ‘to make the point that a process has been set in motion with an unpredictable end, to direct strikes against Kyiv at the other end, with battlefield nuclear use in the middle’.

Much of this should sound familiar to British ears.

Back in November 1993, Tory defence secretary Malcolm Rifkind admitted that the threat of an all-out nuclear assault with all Britain’s Trident missiles might not be ‘credible’ against certain enemies. Rifkind said it was therefore important for Britain to be able to ‘undertake a more limited nuclear strike’ to deliver ‘an unmistakable message of our willingness to defend our vital interests to the utmost.’

It became clear that Rifkind’s ‘more limited nuclear strike’ would be carried out by a single (Hiroshima-scale) nuclear warhead on a single ‘Tactical Trident’ missile fired from a British Trident submarine.

According to the respected military journal International Defence Review, Tactical Trident has four possible roles. The first two are to reply to either nuclear or biological/chemical attacks by the enemy in a large-scale conflict like the 1991 Gulf War.

‘Thirdly,’ the IDR went on, Tactical Trident ‘could be used in a demonstrative role, i.e. aimed at a non-critical, possibly [!] uninhabited area, with the message that if the country concerned pursued its present course of action, nuclear weapons will be aimed at a high-priority target.’

It sounds as if Western experts think Putin has been reading up on the Rifkind Doctrine and Britain’s ‘sub-strategic deterrence’ policy.

Oh, what about the fourth role? The IDR said: ‘Finally, there is the punitive role, where a country has committed an act, despite specific warning that to do so would incur a nuclear strike.’

Only role 1 had a nuclear armed enemy

New threats

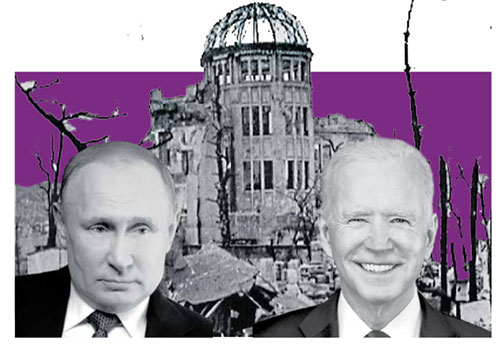

September saw new nuclear threats from Russian president Vladimir Putin, as well as nuclear threats from US officials including president Joe Biden. (We unfortunately also saw responses from Western peace groups that refused, once again, to mention the past history of US and British nuclear threats.)

On 21 September, Putin appeared on television to announce the mobilisation of 300,000 Russian reservists, responding to Ukraine’s recent military successes pushing back Russian occupation forces in eastern Ukraine.

Putin said, in the Kremlin’s official translation: ‘In the event of a threat to the territorial integrity of our country and to defend Russia and our people, we will certainly make use of all weapon systems available to us. This is not a bluff.’

Putin said he was directing his words at ‘those who are using nuclear blackmail against us’. Some observers suggested optimistically that this just meant the NATO alliance, as Ukraine itself doesn’t have nuclear weapons and therefore can’t make nuclear threats.

Unfortunately, this is an inaccurate reading of the speech.

One example Putin gave of nuclear extortion was ‘the Western-encouraged shelling’ of the Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plant which ‘poses a threat of a nuclear disaster’. As the Kremlin accuses Ukraine of carrying out these artillery attacks, this means Putin was threatening the Ukrainian government with nuclear attack.

Putin made it clear that he was threatening Ukraine, not just NATO, in his 30 September speech about the Ukraine war: ‘The United States is the only country in the world that has used nuclear weapons twice, destroying the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. And they created a precedent.’

The precedent is that it is morally and legally acceptable to win a war, and avoid loss of life among your own troops, by dropping low-yield nuclear weapons on two enemy cities, killing perhaps 200,000 people, even if the enemy you attack has no nuclear weapons of their own.

Putin also mentioned the destruction of Dresden and other German cities – ‘without the least military necessity’ – by US and UK bombers in the Second World War, as well as the carpet-bombing of Korea and Vietnam (along with the ‘use of napalm and chemical weapons’).

These are all precedents that the US has set for war. Therefore, the US cannot complain if Russia follows in its footsteps and carries out similar actions in its war in Ukraine. That was Putin’s message.

He is logically correct about US hypocrisy, although these arguments would not make such horrifying actions legally or morally acceptable against Ukraine.

US threats

In his 21 September speech, Putin talked about ‘the statements made by some high-ranking representatives of the leading NATO countries on the possibility and admissibility of using weapons of mass destruction – nuclear weapons – against Russia’.

Many commentators have said Putin was talking rubbish but, actually, Western leaders have made very threatening noises.

On 24 March, for example, US president Joe Biden said that, if Russia used chemical weapons in Ukraine, this ‘would trigger a response in kind’, suggesting either chemical or nuclear retaliation.

The then British prime minister, Boris Johnson, added: ‘You have to have a bit of ambiguity about your response, but I think it would be catastrophic for him if he were to do that, and I think that he understands that’ (emphasis added).

Here is where it helps to know a bit of history. Here’s a Guardian report from 4 February 1991, in the run-up to the Gulf War, talking about Douglas Hurd, then British foreign secretary: ‘Mr. Hurd said that if Iraq responded to an allied land assault by using chemical weapons, President Saddam [Hussein] would be certain to provoke a massive response – language the U.S. and Britain employ to leave open the option of using chemical or nuclear weapons.’ (emphasis added).

This was one of eight British and eight US nuclear threats against Iraq in 1990 – 1991 documented in the CND briefing, Nuclear Targeting of the Third World written by me and the then CND information officer Declan McHugh.

Putin’s 21 September threat came just days after Biden had appeared on US television to warn Russia against using chemical or tactical nuclear weapons in Ukraine. Biden told CBS News on 17 September that the US response would be ‘consequential’: ‘depending on the extent of what they do will determine what response would occur’.

On 25 September, US national security advisor Jake Sullivan repeated Boris Johnson’s threatening words from March. Sullivan said repeatedly on US TV that there would be ‘catastrophic’ consequences for Russia if it used a nuclear weapon in Ukraine – because ‘the United States will respond decisively’.