When I was 15 or 16 I saw a film which has remained a favourite with me – and millions of others I suspect. An American in Paris (1951) starred Gene Kelly, the debuting Leslie Caron, and Hollywood’s fantasy version of Paris. A couple of years ago, I wrote a poem, ‘Confessions of a teenage narcissus’, and it contains these lines:

I wanted to look like Gene Kelly

I wanted to be

that American in Paree (Paris)

I wanted Gene Kelly’s loafers

I wanted his white socks

I wanted his track-top

I wanted the cut of his slacks

I wanted his sports-coach cap

I wasn’t au fait

that he wore a toupée

Last November a friend gave me a birthday treat and took me to the stage show version of the film. Currently on in London and in receipt of well-deserved rave reviews, it delighted us both but also gave us pause for thought. The show is not absolutely flawless but it does something the film never did and that’s to use its stunning opening sequence to give the story some pre-history as well as a political/social/cultural frame of reference.

In this rapid and fluid sequence, the Nazi banners of occupation fall to the ground, the French tricoleur rises and the stage is filled with scenes of life in newly-liberated Paris. French soldiers return from POW camps, US soldiers dig the boulevards, a young woman is beaten because she had a German soldier boyfriend, spivs and gangsters ply their trade, young men and women dance in cafés; the city is in celebration and confusion as France tries to live down the shame and humiliation of the occupation.

In their different ways, both film and stage show tell us something quite profound about those times. In the film, Kelly’s character – a painter named Gerry Mulligan (‘Mooligan’ as the French call him) is in Paris because in his view – and probably that of the film-makers – Paris is still the capital of the art world, and that’s where he has to make it. He probably has a Bill of Rights grant to study, which was the right of US military personnel demobbed after the war.

The irony is that, in the 1950s, a swathe of US painters – Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Lee Krassner, Willem de Kooning et al – turned New York into the undisputed capital of the art world.

A further irony is that, in the film, Gerry Mooligan recognises that he’s not very good and is unable to fool himself. On stage, he seems less aware but his naive and clumsy attempts at modernism are echoed in the sets and even in the costumes of the corps de ballet and we are left to decide his worth.

The show is beautifully dressed and moneyed women characters wear clothes in the ‘New Look’ style created by Christian Dior in 1947. It’s extraordinary that, only a couple of years after the war, Paris had re-launched itself as the capital of fashion and remained so till the centre of gravity moved to London around the late ’60s.

More interestingly, in the film, Leslie Caron plays a young woman about to marry a man out of loyalty not love. His family protected her during the war years and her name is Lise Bouvier. Interestingly, US president John F Kennedy’s wife’s maiden name was Jacqueline Bouvier. On stage, Lise’s name has been changed to Lise Dassin and as the show specifically identifies her as Jewish her feelings of obligation become clearer.

During the McCarthyite period of anti-Communist hysteria in the USA in the ’50s, the celebrated film director Jules Dassin was banned from working in the US, and had to move to France. I’d known his work from that period – for example, the hugely influential heist movie Rififi and the equally successful Never on a Sunday with music by the left-wing Greek composer Manos Hadjidakis – and had assumed he was French.

Actually he was of Polish-Jewish descent. Lise being given his name seems more than coincidental.

Whether or not that’s the case, the stage show has a welcome resonance with our times, when many political commentators de nos jours are concerned that US president Donald Trump has ushered in a new era of political hysteria and retribution. And then, of course, there’s the little matter of the meaning of ‘Europe’.

Last word, though, must go to The Red Propellers. I’ve mentioned this ace band before in my column because it is politically/socially/poetically-engaged. Who else writes songs about Pussy Riot and Chelsea Manning? Anyway, the RPs have a spiffing new double A-side single out on 45rpm vinyl: ‘Johnny Johnny/Sandi says’ on Roller Coaster Records/ Long Black Coat Records. Google ’em.

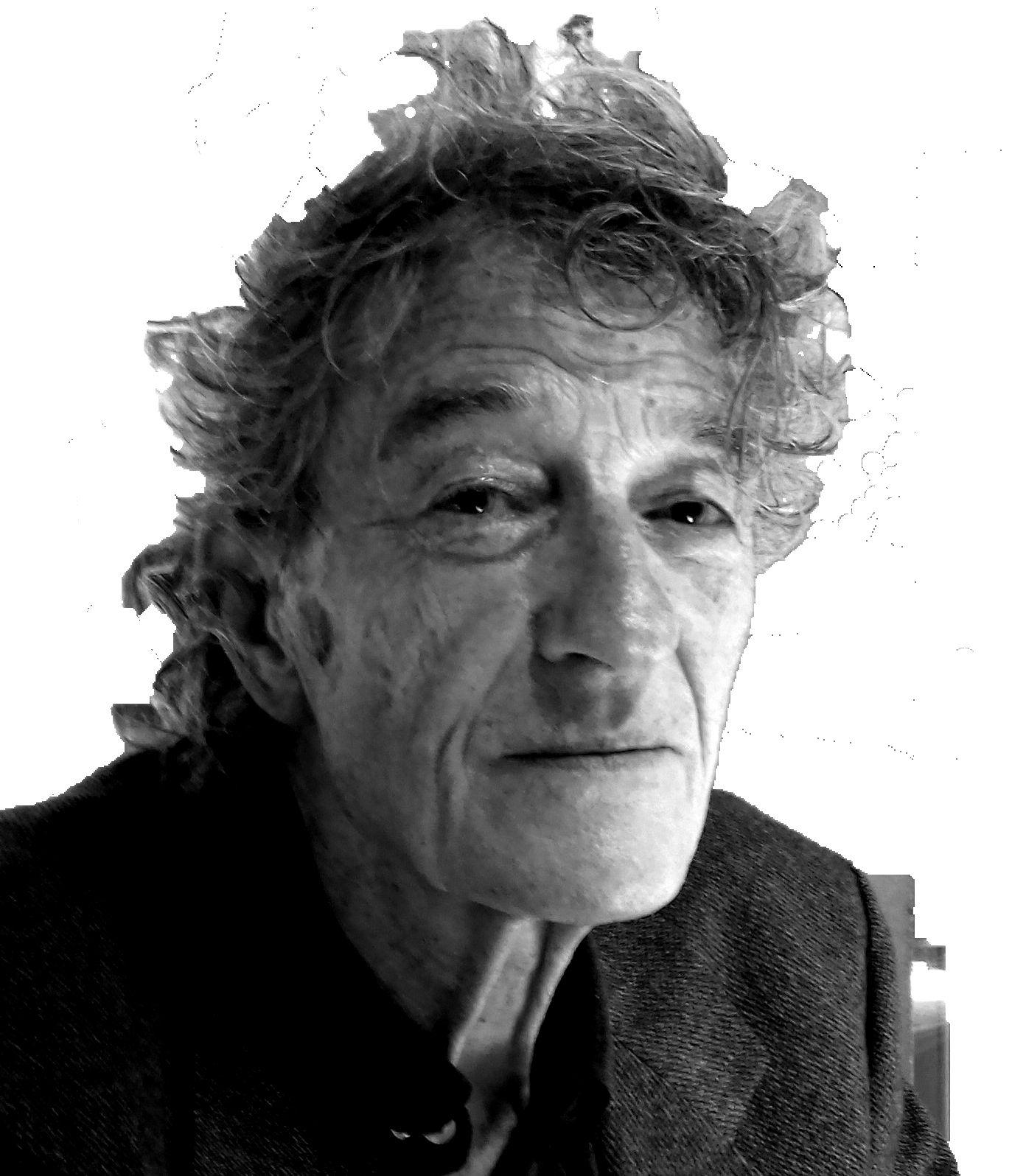

See more of: Jeff Cloves