When I was 14, in the winter of 1978, I travelled down to London from the north-west with my mum to see the Dada and Surrealism Reviewed exhibition at the Hayward Gallery. It remains my number one gallery experience.

45 years later, not one but two seminal feminist exhibitions in London have elbowed their way into my all-time gallery Top 10.

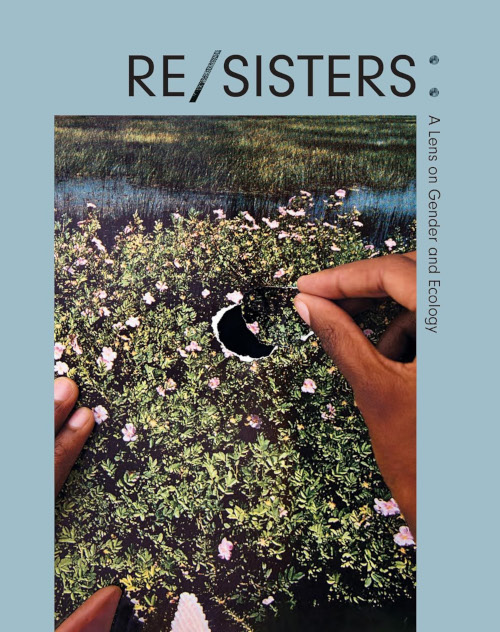

The last edition of PN profiled the remarkable Re/Sisters exhibition at the Barbican, which closed on 14 January. You can still order the catalogue from your local library or bookshop. It’s a weighty, hard-backed tome, jam-packed with thought-provoking and beautiful imagery.

The Re/Sisters book, like the exhibition, starts with a large format Barbara Kruger image from 1984, a photograph of a woman’s head resting upside down on the ground, with leaves placed over her closed eyes. The text running above and below says: ‘We won’t play nature to your nurture.’

It’s an excellent mantra for the exhibition which included a wealth of thoughtful and exciting eco-feminist imagery and installation, from Laura Grisi and Judy Chicago in the late 1960s to contemporary documentary photography by Sim Chi Yin. The latter maps the emergence of artificial privatised islands in her home country of Singapore and across Malaysia and China.

It was a pleasure to see work by UK artists including: documentary photography of the women’s peace protests at Greenham Common; films and photography by Christine Binnie and the Neo Naturists from the 1980s; Fay Godwin’s beautiful images from her 1990 Our Forbidden Land project; and contemporary documentation of the oily coast around the Caspian Sea by Chloe Dewe Mathews.

Equally, it was exciting to see archival photography and film from around the globe.

My contemporary favourites included photographs by Uyra, an indigenous artist, biologist and educator from Brazil, and a film by Zina Saro-Wiwa about cultural resistance to ecological genocide in the Niger Delta, projected across three screens.

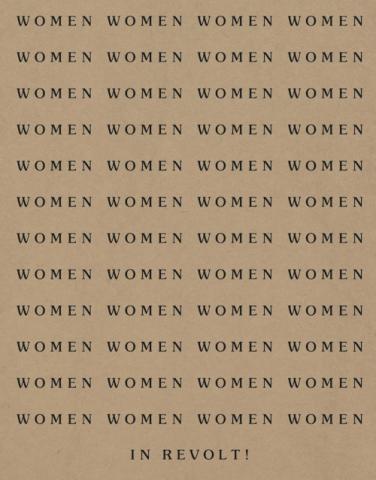

If you missed Re/Sisters, the good news is that Women in Revolt is still on show at Tate Britain until 7 April.

It also includes work by the Neo Naturists and documentation of Greenham Common. But while the atmosphere in the Barbican galleries was focused and reflective, the excitement of the Tate Britain audience was palpable when I visited – despite it being a gloomy Monday evening in November, the galleries were busy with a multi-generational audience.

In contrast to that Surrealist exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1978, much of the artwork in Women in Revolt! has been created by women only a few years older than me – and some artists, including Poulomi Desai and Amanda Holiday are younger.

Looking back on these years of late-second and early-third wave feminism was a revelation.

It was enthralling to see so many powerful graphics and soft sculptures. The works by Cosi Fani Tuti, the documentation of the Grunwick strikers, and the excellent documentation of lesbian activism and black and disabled activists from the ’70s and ’80s were particularly exciting to see.

It reminded me that while the world is far from perfect now, many of the battles that we fought from the 1960s to the ’90s have been won – or, more sinisterly, that the battleground has shifted.

Back in the 1980s and ’90s, it was still possible for women to receive state benefits while being unemployed, and to remain financially stable enough to throw their efforts into full-time activism.

Now – with benefits much lower, and rents and the pressures to find full-time work much higher – it is much harder for women of working age to be full-time activists. And with mobile phones and social media, the days of organising a mass invasion of a military base by word of mouth alone are a thing of the past.

In 1989, the Guerilla Girls created their famous poster pointing out that 5 percent of the artists in the modern art sections of the New York Metropolitan Museum were female, yet 85 percent of the nudes were female.

While naked women are still a part of the imagery in both exhibitions, the use of nudity is entirely within a feminist context.

It has taken 35 years for it to become a reality that exhibitions with an international profile exclusively present artists who are female or LGBTQ+ – and with a significant proportion being global majority artists.

These two high-calibre exhibitions reflect important national and global narratives.