"Here I stand", said Martin Luther, "I can do no other"; My initial image of conscientious objection was rather framed by the Protestant tradition of the individual conscience taking a stand against authority, nailing theses to church doors and going to the stake rather than renouncing their faith. I understood it as a personal moral imperative rather than as a political strategy.

That, too, is how I think states have understood conscientious objection (CO). By the end of the twentieth century, it had become normal to interpret the right to “freedom of conscience” as including objection to military service, and for states to make provision for those who object. What objectors generally have wanted, however, is not to be treated as exceptions - people of “tender conscience” - but rather to challenge militarism, to oppose the preparations for war or even war itself, and to withhold their own cooperation from war in a way that would encourage others to do the same.

Sometimes, it has to be said, some Western European “CO unions” have lost sight of this. The first time I read a report of one of their meetings (in 1985), the burning issue was “discrimination” because substitute service lasted longer than military service and was worse paid. Although the activists in the Finnish Union of COs always maintained a stronger anti-militarism, the most bored audience that ever sat through one of my talks were Finnish COs obliged to attend a series of lectures as part of their substitute service.

Objection as disobedience

In contrast to the routinised consequence of CO manifesting as substitutory service, CO can also be a strategy of non-cooperation with militarism and war preparations. Objection as a form of civil disobedience transforms a personal commitment into a public act. From Moscow to Izmir, from Budapest and Wroclaw to Port Elizabeth, from Medellin to Tel Aviv, I have met objectors who were advised that this was not the time to expose themselves to the risks, but whose actions subsequently changed the climate of debate in their countries. Open defiance with a willingness to take the penal consequences dramatises the issues.

CO in wider struggles

Objection to military service also has a prophetic role, promoting other values, prefiguring a better world.

In the epoch before the First World War, the ideal of international workers' solidarity was at its height and anti-militarists advocated tactics such as an international general strike against war. Unfortunately, the call of nationalism was stronger, yet there were still many who would not fight a bosses' war but rather believed that workers should unite. In apartheid South Africa where only whites were conscripted, the objectors were rejecting both militarism and apartheid, but further than that they were demonstrating that if whites wanted racial equality they had to commit to it and suffer repression.

Objectors from “enemy” states - from both sides of the Cold War, or from Greece and Turkey - have signed “personal peace treaties” expressing their support for each other and making a joint commitment to work for values that undermine the hostility of their states.

Objectors deny the states legitimacy to decide issues of life and death - sometimes in the name of a higher good, sometimes in the name of their own community. These converged in the 1980s in the Baltic states where objectors refusing to serve in the Soviet army invoked the Geneva Convention that a state should not conscript citizens of occupied territories.

The most significant acts or campaigns of objection are often not pacifist. There are those whose experience of the military leads them to objection, those who, despite their military training, reflect on what they are doing and reject nuclear weapons, those who refuse particular wars. Perhaps there has never been such a pluralist resistance as that that now exists in Israel. More than 1000 Israelis reservists have announced their refusal to serve in the Israeli Army, and more than 30 of them are in prison. They are acting with widely different attitudes - many still willing to serve in the Israeli army as long they stay within Israel's own borders, but some rejecting military service; some are Zionist, some non-Zionist. Yet they have signed a common declaration and each is seeking to influence their own circle of opinion to break with Sharon's campaign of terror.

The limits of objection

I cannot write just in celebration of the strategy of CO as civil disobedience. It has its limitations. Most obviously is that the main protagonists in the strategy are those liable to conscription, usually draft-age young men. However, even within that sector, those most likely to think of civil disobedience are normally middle class, people who enjoy a certain space to reflect on such issues and to make choices.

Public refusal is rarely the only choice for those who want to avoid military service. There are usually other means - legal and illegal - and for every person who seeks a nonviolent confrontation with the state and is prepared to court prison, more are likely to choose these other means. Moreover, when we look at the kind of activities that eroded the US's armys war-fighting capacity in Vietnam, alongside the formal conscientious objection of those who registered and the draft card burning of those who chose civil disobedience, we must also place desertion, evasion, forming soldiers' peace groups, using drugs and firing on officers. Each of these varied forms of resistance were significant although it is complex to map out how they interacted strategically because each form of action tended to arise within a somewhat different constituency. It seems unlikely that white university graduate draft resisters sitting in prison during the Vietnam war would have had much influence on Afro-Americans living in ghetto and facing the call-up. Yet in a larger picture, perhaps the draft resister's challenge to the legitimacy of the military opened a space for the ghetto kid to think about other options.

The Turkish army has been waging a war in the south-east (Kurdistan) for nearly 20 years, during which hundreds of thousands of Turkish men have contrived to avoid military service. None have had the impact of Osman Murat Ulke's open declaration of conscientious objection and multiple prison sentences. At the same time, it should be noted that despite a couple of years of careful preparations for Osman's resistance - both internationally and locally - and despite the years of war and atrocities, his powerful example has not triggered a more widespread war resistance. Some others are prepared to follow his example, but they remain just as marginal.

”Huh, that's just the kind of encouragement our Turkish comrades need,” I imagine some readers protesting. I think that Turkish anti-militarists are quite aware of their own realities. Indeed the more stubborn they are personally, the more aware they are that the militarism that they are contesting is the central ideology of the Turkish state. To undermine its legitimacy is a long haul. They know it will not be achieved by a few “heroes” and martyrs, but that solid support structures need to be built up around each person prepared to make that stand.

They know too, especially the large number of anti-militarist women, that this is not something to be left to young men. There is not yet conscription for women in Turkey, but already feminists are signalling their resistance to proposals to introduce it and discussing pre-emptive civil disobedience such as violating sections of the penal code that prohibit criticism of the military.

The pacifist moral imperative of “Here I stand” is not enough. Instead, objection has to be conceived as part of a strategy to widen the cracks in a power system and to create a different kind of political space.

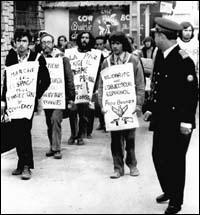

International march in support of the first Spanish CO, Pepe Beunza, from Geneva to the Spanish border. Marchers were beaten by Spanish police and forbidden to enter Spain.

International march in support of the first Spanish CO, Pepe Beunza, from Geneva to the Spanish border. Marchers were beaten by Spanish police and forbidden to enter Spain.

Spanish insumision

For me, the most inspiring movements of objection have been those resisting war (real or imaginary) and linking with other social issues to gain a stronger public resonance. However, of all the “peacetime” movements, I think the Spanish MOC since 1989 has been the one that has most consciously tried to overcome the limitations of CO strategy. Its campaign of insumision (refusal) has played a significant role in accelerating the end of conscription in the Spanish state. In the MOC strategy, each insumiso was to contribute to the social base of the campaign by forming a support group including people not personally liable to conscription but who were willing to incriminate themselves as having incited insumision. Particular groups were formed for parents, but also MOC introduced war tax resistance - a demonstration that refusing militarism is not just a youthful episode but can carry on throughout ones life. MOC has carried a strong utopian element - the nonviolent defence it advocates is not of this society and its hierarchies. These days, when MOC as an organisation is much weaker than it was, its influence remains visible throughout the social movements in Spain.