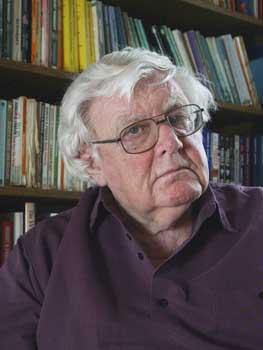

Albert Hunt, critic, playwright and educator, and former staff member and drama critic of Peace News, was part of the wave of innovators that transformed the British theatrical scene in the 1960s and 1970s and pioneered an approach to adult education based on the active participation of students in games and creative improvisation.

Born in Burnley in 1928 to a working-class Pentecostal family, with a radical pacifist tradition, he was a conscientious objector to military service in the 1940s. When a nurse hesitatingly informed his mother at his birth that he had a deformed right hand with no fingers and only two stumps where his thumb and little finger should have been she responded: ‘Well at least he’ll never have to go to war.

Much of his theatrical and educational work reflected his enduring political concerns but also, crucially, his commitment to raising them in a way which was both entertaining and encouraging of open debate. Brecht provided the model, and, among contemporary playwrights, John Arden, a study of whose plays he published in 1974 (Arden: A Study of His Plays, Eyre Methuen).

After graduating from Oxford, he taught at a grammar school at Swaffham in Norfolk. I first met him at that time when he and others provided invaluable local support to those of us in the Direct Action Committee against Nuclear War, campaigning against the construction of a US nuclear missile base in nearby North Pickenham. In 1960, he became adult tutor to Shropshire and in 1965 took up the post of head of Complementary Studies at Bradford Regional College of Art where he formed the Bradford College Theatre Group, which staged some of his best productions.

In 1966 he collaborated with Peter Brook in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of US, about the war in Vietnam, a formative experience, which he drew upon in his college work and theatrical productions. The latter included a re-enactment by 300 students of the Russian Revolution in the streets of Bradford, and a symbolic representation of the allied bombing of Dresden in February 1945, in which stacked cardboard boxes representing the city were systematically destroyed with handsaws, scissors and a metal bar while one of the actors read aloud David Irving’s account of the raid in his book, The Destruction of Dresden. The group later toured the performance to acclaim in Dresden. During all this period, starting in the late 1950s, in addition to his drama and film criticism for Peace News, he contributed reviews for the theatre magazine, Encore, New Society, The Guardian and other publications.

Albert revolutionised the teaching of Complementary Studies in Bradford. The compulsory weekly classes were abandoned in favour of fortnight-long projects run by himself and his staff, or by visiting artists and specialists. Among these were the film and theatre critic Alan Lovell - also a regular contributor and former editorial staff member of Peace News - the poets Adrian Mitchell and Michael Horowitz, the dramatists John Arden and Margaretta D’Arcy, the artist and performer, Bruce Lacey, and the architect Edward Cullinan.

In 1968, at Albert’s invitation, I ran a project at the Art College based on Orwell’s 1984, and the following year moved to Yorkshire and joined the department. It was an exciting time to be in Bradford. The Art College staff included the Liverpool poet, Adrian Henri, the surrealist artist Tony Earnshaw and the musician and creator of multiple shows and happenings, John Fox, co-founder of the Welfare State International. There was also a lively arts and theatre scene in Bradford outside the college context which included the political theatre group the General Will Company, the Theatre in the Mill, and the Bradford Festival which had a strong internationalist flavour reflecting the varied cultural and ethnic mix of the city’s population. David Edgar, today one of Britain’s leading playwrights, cut his teeth on the alternative theatre scene in Bradford during this period.

Albert’s funeral at Elland, near Halifax, in October, was conducted by his family and billed as his ‘Last Performance’. He himself was present in the form of a video accompanying himself at the piano at a family gathering last Christmas. All the proceedings were carried out in his innovative theatrical style including a reprise of The Bombing of Dresden but this time reflecting its regeneration, with flatpack cardboard boxes being constructed by the participants who were invited to write something they remembered about him. I wrote about the time I gate-crashed a rehearsal of US to seek his advice about disguising George Blake as a black man if we succeeded in freeing him from Wormwood Scrubs prison where he was serving a 42-year prison sentence. We were unable to follow up on his advice, but the day after the escape hit the headlines I received a one-word postcard from Albert which read simply ‘Congratulations!’

Albert is survived by his wife Dorothy, his children Christopher, Matthew and Catherine, and three grandchildren.