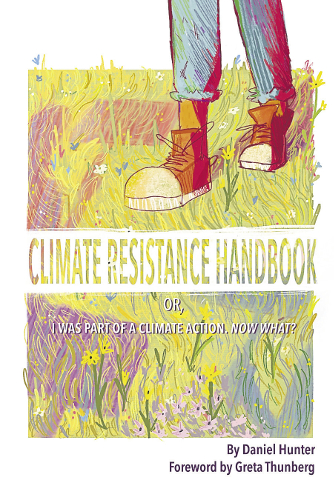

This is an extract from The Climate Resistance Handbook – or, I was part of a climate action. Now what? written by Daniel Hunter with a foreword by Greta Thunberg. Published by 350.org, this 68-page book is being mass distributed in the UK at cost price by Peace News.

Hashbat Hulan was disgusted with her government. The situation in the 1980s in Mongolia was harsh. Mongolians were ruled by a tough authoritarian government. The government crushed all dissent, leaving one political party – their party.

As a student, Hashbat decided to make a change. She met in secret with other young people. They discussed forcing a governmental change. Some said it couldn’t be done. But Hashbat and others continued.

“The second decision was to switch tactics, and escalate. Doing the same tactics would become routine.”

The young people were taking an enormous risk. They knew the government would use force to stop them. The government had nearly wiped out the whole Buddhist community. It had killed one out of five monks; most of the rest had fled.

But Hashbat also knew people were tired of the current situation. Not just tired – angry and frustrated. That anger had no outlet until Hashbat and her friends came up with a public action.

On International Human Rights Day in 1989, the youth risked a protest. The government had carefully planned a series of speeches and military parades. It was in the great square, in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar.

The youth organised a group of about 200 people. The protestors stood with banners opposing the government’s rule and chanted louder than the rock bands the government had paid for.

This got people’s attention. The protestors were not the first to have this feeling. But they said it aloud. They gave voice to a feeling that had been kept silent by fear. At the time, most of the adults just whispered about the protests. Youth around the country copied them with marches of their own.

Hashbat then faced the question every movement faces over and over again: What next?

The youth took two paths quickly. The first was to create an organisational structure so they could make decisions and decide their goals.

They also needed to choose tactics – the actions they thought would get them to their goal.

They settled on a name – the Mongolian Democratic Union (MDU). They created a citizens’ manifesto, with goals such as democratic elections in which any parties would be free to run.

They grew so large they needed a coordinating committee. They didn’t want to operate like the government, with meetings in secret. So the MDU decided to hold open meetings – with over 1,000 members taking part.

The second decision was to switch tactics, and escalate. Doing the same tactics would become routine. They didn’t want to be routine – they wanted to make possible what wasn’t possible before.

And they wanted tactics that would apply pressure on the government to give in to their demands.

It’s like a game of tug of war. They had to keep applying more and more force in order to win.

The youth knew they were in a unique position. Most of the group’s leaders were educated – some were even sons or daughters of government officials. Hashbat was the daughter of a government diplomat. That offered some level of protection. But they knew winning their demands would require sacrifice. Sacrifice meant they would have to take personal risks.

Their tactic: Go on a hunger strike until their demands were met.

Many of the youth activists had studied India, Russia, and China, where hunger strikes were sometimes successful, and sometimes not. It doesn’t work if people don’t know about it. So they held the hunger strikes in the public square – where everyone could witness them.

Hashbat and others started the hunger strike on 7 March 1990, at 2 pm, when the temperature in the square was -15 °C. That really got people’s attention.

They also knew they had to recruit allies. They reached out to a wide range of civil society groups. Five hundred workers at a nearby mine stopped work for one hour in solidarity. Monks joined and offered their support. Teachers went out on their own strikes.

Change was in the air. The pressure mounted on the government, which tried negotiations and offering weak compromises to stop the energy. But the youth – and now the other groups, too – refused to accept anything more than their core goals.

This brought in more allies and opened up space for more tactics.

And they won. The government reluctantly announced democratic elections with all political parties able to participate. The struggle wasn’t over, but the youth had won a huge victory.

Like a wave

There are lots of lessons on how social movements win in this story. You win by using a range of tactics. You escalate so that you keep applying more force on your opposition. You win by ignoring the people who say you can’t win. You organise allies, you sacrifice, and you keep active.

One key lesson is they helped birth a movement.

Movements are forces of collective energy, carrying deep emotions like anger and love and moved by hopes and dreams for large-scale change. You know it’s a movement because of the momentum and growing energy.

Movements are like a wave. They are a bundle of energy made up of many parts.

The movement is not just one group or organisation. The MDU was joined by teachers, workers, and monks. Each group had its own part, its own methods, its own tactics. But the overall feeling was what made it a movement.

“When we’re in the middle of a movement, it can look chaotic and disorderly.”

Movements are sometimes easier to see from afar (which is why, in the Climate Resistance Handbook, I tell stories both of climate justice movements and other social movements). When we’re in the middle of a movement, it can look chaotic and disorderly. Movements are not clean. They are messy. And when inside them, we are painfully aware of their shortcomings.

Most people don’t notice movements when they are small. Nobody in Mongolia knew how big that first protest was going to become. People only notice movements when the wave has gotten big enough.

This fact is important because it makes the humble work each of us does, however we are contributing, meaningful if we are in touch with the energy of the movement.

Understanding movements helps us understand how our actions are part of a bigger whole.

Movement myths

When we study movements, we have to face a problem: we have been lied to about how change happens.

Myth: Movements are lit like a match.

Movements don’t appear from nowhere. The young people in Mongolia had met for months in secret. Before that, others had tried experiments but failed. The youth spent time learning from them (and others outside of Mongolia).

Yet a history textbook might skip all of that and begin the story with thousands of people supporting the strikers.

The myth that movements ‘suddenly appear’ ignores the early stages. It ignores how we have to build up small networks. It makes big actions seem more important than the early, small ones. And it skips over skill-building and studying other movements.

Myth: Movements are built by heroic figurehead leaders.

When we think of famous movements, we may only think of Martin Luther King Jr, Mohandas Gandhi, or Nelson Mandela.

But movements are more than heroic leaders.

Some movements have them. Some don’t. But all movements are built by many organisations, groups, and loose-knit networks that organise and act together for change. No organisation, action, or individual speaks for an entire movement.

Myth: Movements require complete internal unity.

People act as though past movements had a clear vision, a clear plan, and all agreed. But that was never the case.

The young Mongolian activists argued and disagreed. They had internal splits about tactics and policies. Successful movements always have internal disagreements and division.

Working for unity is great – and so is accepting the reality that we are not all going to see things the same way.

Myth: Petitions (or any single action) are a movement.

This myth goes like this: Want to stop the fossil fuel industry? Get a big petition! Or get everyone to do a social media share! Or a big march!

But in reality, no single tactic is a movement. A movement requires many different types of tactics.

Some tactics, anyone can do. Others will require higher personal risk than most people are willing to take.

Some tactics, maybe only some people can do, like a lawyer filing a lawsuit or the mine workers going out on strike.

Movements require lots of different types of tactics – and relying on just one action will not result in change.

Myth: Movements succeed when they mobilise large, mass actions.

Countless times the refrain is heard: ‘We just need to have a giant march.’

However, movements don’t win because of singular actions, however big. That can lead us to always try to organise big actions.

Then we dismiss small actions, like those done in rural areas, communities who just joined us, or powerful but experimental tactics.

And we can’t just keep organising for the one big action. Movements need ongoing resistance – otherwise, the people in power can just wait until the event is over and continue ignoring movement requests.

Movements require sustained pressure for change at many levels. It takes time to build, but without ongoing resistance, movements don’t achieve their goals.

Myth: Movements only work in democratic countries, or where they don’t have police repression.

Nonviolent social movements have overthrown powerful, oppressive regimes in the Philippines, Chile, Bolivia, Madagascar, Nepal, Czechoslovakia, Indonesia, Serbia, Mali and Ukraine, to name a few.

Powerful social movements occur frequently in repressive countries. In democratic regimes, people may rely on traditional channels for advocating social change (courts, elections, etc).

But in places with harsh rulers, they have saved a step: people already know those institutions won’t save us. We have to organise ourselves.

While organising looks very different from in democratic countries, groups have found ways to build movements even in the most repressive countries.

Myth: Movements need media attention to win.

This myth is common. And it’s true that media can help influence public opinion.

But it’s not healthy for a movement to associate the health of the movement with how much media coverage it is getting .

The Mongolian youth would have been very frustrated if they had to rely on state-sponsored media to win. That’s why they did their hunger strike in a public square.

If we believe we are effective because the media are covering us, then what happens when the media get bored and decide to stop covering us? Movements are related to the people – and the media is just one avenue to speak to them.

Each of these myths makes us look outside of ourselves. We look for the heroic leader, the right circumstances, or what the newspapers say about us. That’s not power. Movements are most effective when we look inward and find strength in ourselves and our relationships.

These myths help us see power in the wrong way. To see it the right way, we need to understand the upside-down triangle.

A new view of power

The dominant view of power is that it flows from the top downward.

A student does what their teacher tells them to do. The teacher takes orders from the principal. The principal takes orders from their administrator. And so on, all the way up the pyramid to the head of state.

On climate change, we might see fossil fuel companies at the top. They buy our heads of state and leading politicians.

Those politicians oversee government commissions that are supposed to regulate companies but instead violate land and workers’ rights.

Those commissions then approve the bosses’ plans, who then order workers to clear land and dig oil out of the ground. And so on.

In that view of society, everyone below follows orders from someone at the top.

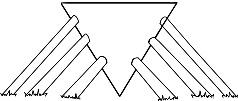

But there’s another way of helping groups view power: the upside-down triangle.

An upside-down triangle is always going to be unstable. An oppressive system that relies on destroying our planet is unstable. It’s not natural to burn this much carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases. The system needs to be held up by pillars of support.

The pillars make the structure seem legitimate and right.

Pillars can be the laws, courts, media, and schools that train us to obey.

Other pillars include people who may oppose the system but still help keep it running – including administrators, regulatory bodies, academics, and teachers – who refuse to speak out against what’s wrong.

This view reveals how much power we actually have. The most repressive Mongolian government is forced to the negotiating table if its youngest citizens refuse to eat. If we don’t comply, the system doesn’t keep going.

“The upside-down triangle reveals how much power we actually have.”

Groups can use this tool to look at their work and develop a more complex and accurate understanding of power.

Being able to see the pillars of support that keep bad policies in place can help expand our sense of how we can make change.

A group of young people in Serbia nonviolently fought their powerful, ruthless dictator in Serbia.

They required every person who joined their movement to learn the upside-down triangle. They led trainings to explain the concept and their plan to remove the pillars they saw. They explained it this way:

‘By themselves, rulers cannot collect taxes, enforce repressive laws and regulations, keep trains running on time, prepare national budgets, direct traffic, manage ports, print money, repair roads, keep food supplied to the markets, make steel, build rockets, train the police and the army, issue postage stamps or even milk a cow. People provide these services to the ruler through a variety of organizations and institutions. If the people stop providing these skills, the ruler cannot rule.’

This approach was a key ingredient to their movement. And they were successful in overthrowing the brutal Serbian dictator.

This is one of the key insights from nonviolent direct action.

Huge amounts of power live in us.

We can make change by removing the pillars of support. When we remove our involvement, unjust systems become more unstable. And we can make them fall.