An ‘epic fight’ between the broad left and the forces of the establishment has begun (see PN 2586–2587). The prize couldn’t be bigger. The British left, for the first time in decades, has a very real opportunity to implement significant progressive change on the epoch-altering scale of the 1945 and 1979 elections. As Novara Media’s Aaron Bastani tweeted: ‘If we win, and survive, and enact a major program of economic and political change, the whole world will watch. The UK really could be prototype.’

An ‘epic fight’ between the broad left and the forces of the establishment has begun (see PN 2586–2587). The prize couldn’t be bigger. The British left, for the first time in decades, has a very real opportunity to implement significant progressive change on the epoch-altering scale of the 1945 and 1979 elections. As Novara Media’s Aaron Bastani tweeted: ‘If we win, and survive, and enact a major program of economic and political change, the whole world will watch. The UK really could be prototype.’

The June 2017 general election result was ‘one of the most sensational political upsets of our time’, according to Guardian columnist Owen Jones. Despite being repeatedly laughed at and written off by an intensely hostile media, by other parties and by much of the Labour Party establishment itself, Jeremy Corbyn led Labour to its biggest increase in vote share since 1945. Labour leapt to 40 per cent of the vote after the party had achieved 30 per cent under Ed Miliband just two years earlier.

On 20 April, only 22 per cent of people had a favourable opinion of Jeremy Corbyn, and 64 per cent had an unfavourable view. (Added together, that was 42 per cent unfavourable overall). By 12 June, the figures were 46 percent favourable and 46 percent unfavourable. (Overall, neither favourable nor unfavourable.) (YouGov, 15 June).

Though the Tories have managed to cling onto power, Corbyn’s rise has created shockwaves throughout the political system.

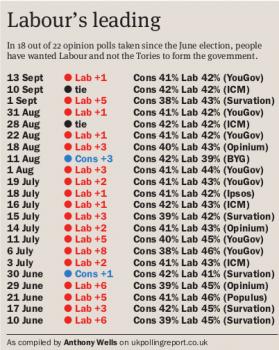

Writing for Open Democracy, Jeremy Gilbert, a professor of cultural and political theory at the University of East London, noted the election ‘was a historic turning point’ as it ‘marked the final end of the neoliberal hegemony in Britain’ (1 August). In response the Tories are reported to be considering relaxing the pay rise restrictions on public sector workers, while Scottish National Party leader Nicola Sturgeon unveiled a range of progressive policies, including possible tax rises, ‘in an effort to reinvigorate her government’ (Guardian, 6 September). With a recent poll from Survation showing Labour on 43 per cent – five points ahead of the Conservative Party on 38 per cent – Jones believes Corbyn now ‘has a solid chance of entering No 10’ (Guardian, 9 August).

Corbyn is a threat

Though some commentators have argued Corbyn’s Labour Party differs little in policy terms from the party under Miliband, ‘those criticisms were dispelled by the election manifesto’, Alex Nunns tells me. Nunns, author of The Candidate: Jeremy Corbyn’s Improbable Path to Power, says: ‘It’s inconceivable that Miliband would have stood on a promise to renationalise energy, water, railways and the Royal Mail’, as Corbyn did.

More broadly, Matt Kennard, a former Financial Times reporter and author of The Racket, explains to me the key is the direction of travel Corbyn represents: ‘The threat Corbyn poses is that he shows that another world is possible.’

Echoing Gilbert’s analysis, Nunns believes: ‘Corbyn is seen as such a threat by the establishment because he would mark a historic break with the Thatcherite consensus that has dominated British politics for three decades.’ The Labour manifesto ‘unashamedly outlined a vision of a different society based on the principles of collectivism and universalism, after decades of individualism and means-tested entitlements’, he says.

‘Of course, what the British establishment fears most about Corbyn is his foreign policy stance’, Nunns notes. Dr David Wearing, a lecturer at SOAS University of London, agrees that Corbyn represents a huge challenge to the foreign policy elite – and conventional wisdom. Though he has had to compromise on Trident and membership of NATO, Corbyn ‘is a straightforwardly anti-imperialist, anti-militarist figure’, Wearing recently argued on the Media Democracy podcast. ‘I can’t think of any time in the last several decades where it has been a realistic possibility that the leader of a UN security council permanent member, a great power, a great capitalist Western power, could be in the next few years an anti-militarist and an anti-imperialist.’

“It’s not enough to just elect a leader and think the job is done”

Kennard agrees: ‘It’s a huge moment in British history – and arguably in world history’. The establishment ‘have every right to be fearful’, he adds.

Rejuvenated Tories

For the words ‘prime minister Jeremy Corbyn’ to become a statement of fact rather than wishful thinking, Labour needs to win the next general election. Standing in their way will be a rejuvenated Conservative party and their powerful supporters, who will likely have learned lessons from their poor performance in June.

According to the Guardian, the Tories have been undertaking an internal review, which will urge the leadership to offer voters clear messages on policy and shake up the party machine (Guardian, 29 August). ‘What didn’t happen in the [general] election was almost as interesting as what did’, Nunns says. ‘There were no doom and gloom threats about a Labour government from big business, there didn’t seem to be an effort to sabotage Labour by the state. Given that even Conservatives now expect Corbyn to win the next election, you’d expect it to be different next time.’

Interviewed on BBC Newsnight, former Labour leader Tony Blair voiced similar concerns on 17 July. ‘The Tories are never going to fight a campaign like that one’, he said. ‘I know the Tories, they are not going to do that. And they are going to have a new leader as well. Secondly, our programme, particularly on tax and spending, is going to come under a lot more scrutiny than it did last time round’.

Barriers With a Corbyn-led Labour Party victory in the next election a real possibility, it is worth considering the challenges it would face. Speaking to Jacobin magazine, Jon Lansman, chair of Momentum and a close associate of Corbyn, is clear: ‘We will face opposition from all aspects of the establishment, from the powerful, from global corporations’.

With a Corbyn-led Labour Party victory in the next election a real possibility, it is worth considering the challenges it would face. Speaking to Jacobin magazine, Jon Lansman, chair of Momentum and a close associate of Corbyn, is clear: ‘We will face opposition from all aspects of the establishment, from the powerful, from global corporations’.

Having reported extensively from the Global South, Kennard notes ‘the method of choice’ for undermining leftist governments ‘in peripheral world economies has been military coups and political assassinations.’ The UK, of course, has a very different political landscape with very different political traditions.

Despite this, it’s important to note that soon after Corbyn was elected Labour leader, in September 2015, the Sunday Times carried a front page report that quoted ‘a senior serving general’ saying the military ‘would use whatever means possible, fair or foul’, to prevent a Corbyn-led government attempting to scrap Trident, withdraw from NATO and ‘emasculate and shrink the size of the armed forces’.

There is also evidence that MI5 attempted to undermine Harold Wilson’s Labour government in the 1970s (see David Leigh’s book The Wilson Plot: How the Spycatchers and Their American Allies Tried to Overthrow the British Government), and Corbyn himself has been monitored by undercover police officers for two decades as he was ‘deemed to be a subversive’, according to a former Special Branch officer (Daily Telegraph, 7 June).

However, though he notes the British establishment ‘has never been tested properly in this way for centuries’, Kennard is quick to clarify he doesn’t expect a military coup or assassination attempt to happen in the UK.

‘We know from history what usually happens when left governments are elected’, Nunns says. ‘They face destabilisation from capital, both domestically and internationally, they are subjected to a hysterical press operation to undermine them, they face diplomatic pressure from other countries, and they have to deal with sabotage from the state they have been elected to run.’

North American radical activist and author of Viking Economics: How The Scandinavians Got It Right – And How We Can, George Lakey tells me the elite ‘will use whatever tactics and strategies will put us on the defensive, because, as Gandhi never tired of pointing out, going on the defensive is a sure way to lose.’ If those trying to undermine Corbyn ‘are smart strategists, they will be flexible and keep trying things that will get progressives to mount the barricades in defence’, he notes.

The Labour leadership are, of course, aware of these likely challenges, and seem to be making early moves to neutralise them. ‘The issue for us is to stabilise the markets before we get into government, so there are no short-term shocks’, shadow chancellor John McDonnell told the Guardian on 19 August, explaining he had been meeting with ‘people in the City – asset managers, fund managers’ to reassure them about Labour’s plans.

Mobilisation is key

Speaking about US politics in 2007, Adolph Reed Jr, professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania, noted: ‘Elected officials are only as good or as bad as the forces they feel they must respond to’.

In the UK context, this means the actions of the movement supporting a Corbyn-led government will need to match – and overpower – the establishment onslaught that will be waged against it.

‘The first 19 months of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership proved one thing above all else – it’s not enough to just elect a leader and think the job is done’, Nunns notes, pointing to the movement’s central role in fending off the attempted coup against Corbyn in June 2016. ‘The need for the movement to stay mobilised will be multiplied by a hundred when Corbyn is in government.’ Moreover, Nunns points out that the movement ‘will have to be on a scale we haven’t seen so far’.

Lakey points to the successful strategies used in 1920s and ’30s Norway and Sweden as examples Corbyn supporters should follow. ‘The movements’ mobilisations took place mainly through direct action campaigns and cooperatives, both of which remained independent of the [political] parties’ that represented them in parliament, he explains. ‘The movements strategised independently because they believed that equality, freedom, and shared prosperity could only come from a power shift in society.’

‘I learned from studying Norway and Sweden that if they had relied on parliament and the electoral process, they would still be waiting for the power shift that in the 1930s enabled them to invent the Nordic model that has outperformed Britain and the US for over 60 years’, Lakey continues. ‘From the perspective of power, parliaments negotiate and express change, they don’t make change.’

Kennard is strongly in favour of joining the Labour Party and hitting the streets to campaign. ‘I door knocked for the first time [during the June general election] and I’ll do it again’, he notes. Indeed the importance of traditional campaigning techniques was highlighted by a London School of Economics study which found the seats where the Labour leader campaigned – often holding large rallies – saw an average swing of 19 per cent in the Labour Party’s favour (Independent, 15 August).

Kennard also supports the democratisation of the Labour Party to give members more say in policymaking and choosing their representatives. Finally, he recommends people get involved on social media. Though sceptical of the medium initially, he now sees platforms such as Twitter as a way to combat the misinformation and lies spread by newspapers like the Sun and Daily Mail.

With the establishment likely to try to put a Labour government on the back foot, Lakey says it is essential that Corbyn stays on the offensive. ‘So avoid trying to maintain any previously-made gains; instead, go forward to make new gains’, he argues.

The general election campaign provided a good example of how successful this could be following the May 2017 terrorist attack in Manchester. Thought to be weak on ‘defence’ by many, Corbyn could have chosen to follow the government’s line on terrorism. Instead he confronted the issue head on, giving a relatively bold speech that, in part, made a connection between Western foreign policy and the terrorist attacks directed at the West. Rather than being cornered and weakened by the government and media, Corbyn took control of – and arguably changed – the narrative surrounding terrorism, with a YouGov poll showing a majority of people supporting his analysis (YouGov, 30 May) [See editor Milan Rai’s article on the PN blog about Corbyn’s speech and ‘foreign policy realism’.]

Defend him and push him

With foreign policy likely to continue to be a significant line of attack on Corbyn, the peace movement has an essential role to play, both in defending Corbyn’s broadly anti-militarist, anti-imperialist positions and in pushing him to be bolder.

For example, Greens such as Rupert Read have criticised the Labour manifesto for pushing for more economic growth in the face of looming climate breakdown (Morning Star, 12 July), while British historian Mark Curtis has highlighted a number of problematic foreign policy pledges contained in the Labour manifesto, including support for the ‘defence’ industry. And despite Corbyn’s historic opposition to both, as Wearing indicates, the manifesto confirmed Labour’s ‘commitment to NATO’ and its support for Trident renewal.

Despite these important concerns, Corbyn’s campaigning and current polling, showing Labour would have an opportunity to form the next government if an election was held tomorrow, puts the Labour Party, the peace movement and UK politics firmly into uncharted territory.