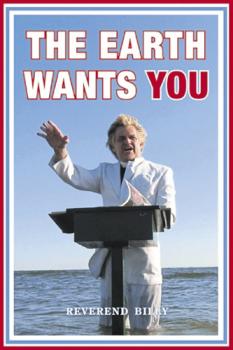

We had arranged to meet up at the Manhattan Gourmet Restaurant [in New York city], a glorified deli at 57th and 6th, right above the F Train station, with the Chase bank looming across the avenue. We carried our toad heads in a big sack.

It was a working-class place with a lunch crowd shouting their orders, lots of laughter. The folks were service workers, spiffily dressed people in retail, Verizon repairmen, security and cleaning people.

There were about 15 of us on this improbable mission: Laura the Diva, Dragonfly, Bryce, Ashlie, Erik Rivas taking pictures, Sylver of Picture the Homeless, Lizzie, Donald Gallagher the Radical Faerie, David Yap and Pat Hornak and Dawn Lookkin and Chido Tsemunhu and Susanna Pryce, and Nehemiah Luckett, our music director.

“No, you should pay us, ’cuz we’re performing for the workers up there because they get so bored.”

Looking back at the pictures of our preparations, I see a UPS driver staring at us over his tray of food. We’re ages 20 to 75, several skin colors and hairstyles, from Mohawk cornrowed, rainbow-dyed do’s to various fades and chops. We’re telling each other to breathe, feeling a little giddy and edgy. We start fitting on our toad heads. Each singer knows which one of the orange cardboard-and-papier-maché constructions fits onto his or her own head. Some of us wear baseball caps to stabilize what amounts to a big off-kilter hat – the protruding lips of the frog jut out over the forehead, so the beak of the cap helps to keep it up off our eyes.

I’m so bored with the USA

We had re-conned the bank earlier, and now we’re reviewing the route, describing the bank’s floor-plan and where the personnel are stationed, where we should walk and who to face when we sing, how to signal to each other that it’s time to stop and leave.

The people at the next table, hair salon or nail shop ladies who have been cackling with gossip since we got here, they tell us if we’re robbing the bank they want a cut to keep quiet. We tell them: ‘No, you should pay us, ’cuz we’re performing for the workers up there because they get so bored.’ And a lady with beehive hair like the Shangri-Las from the ’60s, she says: ‘Oh, I know. And those tellers don’t get paid anything, minimum, it’s terrible. Some of ’em’s on welfare. Can you believe that? Working in a bank and getting food stamps?’

We walk out onto the Avenue, a stream of toad-humans.

It’s raining lightly on our garish, gold-orange reptile heads with the fat black eyeballs. We tread carefully over the potholes in the pavement, steadying our head gear. Following our plan, we stop in the bank’s glassy downstairs lobby where there’s no security, and in fact, no customers either. A semi-circle of ATM machines – with the blown-up photos of smiling actors with checkbooks – stand there looking lonely in the floor-to-ceiling glass enclave with 6th Avenue streaming by.

“Elegant women become suddenly frozen, their eyes lidded, not wanting to admit that a choir of singing extinct reptiles and an Elvis impersonator preacher-type seem to have taken over the bank”

The part of the bank that contains our audience is upstairs at the end of a long shiny escalator. At the top is where we want to hop! We chose this bank because of its strange design – this escalator will deposit our radical toads directly into the midst of ‘wealth management.’ Whereas most bank designs have a more fortress-like defense of their rich clients from the street, this building leaves them more vulnerable to, shall we say, the natural world.

Sympathy for the Devil

We circle up, hold hands and pray to the life of the Earth, and to the memory of our animal guide the Golden Toad, and to the thousands of animals that have run, flown, slithered and jumped into extinction. We ask for assistance in our fight with this Devil. Life around the world is under attack by this fossil fuel bank, the old Rockefeller Standard Oil bank that has always paid for the drilling, gouging, scraping, burning and shipping of the flammable blood of the Earth. Chase Bank is currently the top financier of CO2 emissions. According to Banktrack.org in the Netherlands, it is the single most climate-changing institution on the planet. Sometimes we have so much fun in our church that I have to put the fear of the Devil back into our singers (and myself). Yeah, Chase really IS the Devil.

The toads hop onto the escalator and the action is on.

The Stop Shoppers adopt their crouch, elbows flared out, knees bent in our human approximation of long-legged frogs or toads, rising smoothly toward our interruption.

The escalator delivers us to a little landing pad that opens onto a row of teller windows to the left, and I remember the nasal voice of the beehive-hair lady with her tellers-on-welfare story.

What’s my name?

To the right is a carpeted area where the uptown rich are received. A series of desks and lovely hardwood chairs and little plush couches are a habitat for the six or eight 1%-ers seated with their portfolio managers. The priests of money sit at their computers, reviewing the returns for their demure clients. The rich are here in the middle of the day – elegant women, who upon seeing us become suddenly frozen into impassive-faced John Singer Sargent poses, their eyes lidded, chins turned away, not wanting to admit that a choir of singing extinct reptiles and an Elvis impersonator preacher type seem to have taken over the bank.

Nehemiah has the singers blazing:

‘I’m a frog, I’m a tiger, I’m a manta ray

‘I’m a life in the great death wave.

‘Extinction is my name,

‘Call me Climate Change!’

Everything happens at once. Some of the bankers leave the room, some converge on us, and some sit with the rich ladies as if consoling them. I’m preaching: ‘Stop this banking! Hear the demands of the spirits of life you have killed!’ Nehemiah is comforting people: ‘This is a protest about your investments. It will be over in a minute.’ Lizzie is handing out our research. The toads are moving through the maze of desks, hopping, jerking their black-eyed masks back and forth, fingers splayed out the way frogs do, and always singing the song.

The song’s point of view is an expression from threatened life: ‘I’m a bat, I’m an aspen, I’m a wolverine / I’m a banker’s wildest dream.’ As the preacher, I’m shouting into the gaps of the song the way I’ve learned to do in our concert shows. ‘This is life singing! – Living things giving you – your profit report – your drills, your explosives – your poisons!’

Five minutes, then 10 minutes go by. Laura and Dragonfly are walking between the desks, boldly crossing away from the area in front of the teller windows where I’m preaching. Laura’s grandfather was a leader at the World Bank. She’s not afraid of the rich and their bankers. Dragonfly is fearless too, but from another angle. Her dad was a lifer in the army. Back when Standard Oil was founded her family was just coming out of slavery.

The boldest soldiers from the other side also come to joust. There is one classic red-in-the-face type with the old saw about private property and ‘The police are on their way and you must leave this establishment! This is a crime!’ The toads surround him. Toad-power is real. Consider the species that adopted us with its history: the Golden Toads were killed off in two years by a blast-furnace-hot El Niño that dried up their mountain ponds – this, after having evolved as a species for a million years.

It’s good activism to remember the heart of your purpose at the point when you are most challenged, and that banker backed down in the face of a pile-up of angry life.

The lyrics of the song anticipate opposition: ‘We surround you / You take the names of what you kill / We may be dead but we still sing / We surround you.’ And so the red-faced warrior was surrounded by vengeful toad ghosts. Rough.

Now the extraordinary interruption of the ritual quiet of the bank is creating eddies and swirls of activity across the desks and partitions. Different reactions set in. Bankers are giggling, shouting into phones, frozen and silent, staring out the window. One loan officer is smiling and laughing, taking a movie with his cell phone, like it’s for his kids. Meanwhile, the Golden Toads are singing at the top of their lungs. ‘We surround you! / We surround you! / We may be dead but we still sing!’

Get up, stand up

As adrenalized as I was with my preaching, I remember loving what was happening, thinking: ‘This is church. The life on Earth that we have given ourselves up to, surrendered to, is coming to life here! The dead are singing! It’s Resurrection Time!’

There is the impending arrival of the police to be concerned about, but we must also avoid the increasing risk of our own anger. Although we’re trained in nonviolence, we can become worried that we’re not breaking through, and then naturally we want to apply more force. We feel we must sing and preach louder because of this banker-blowhard in the foreground, but also because of our own fear that we aren’t doing enough.

I want to stay and have debriefings with each banker and each wealthy customer: ‘Do you get it? Will you ask yourselves some questions about Chase? Is divestment a possibility? Are we getting through? After all, given the Earth’s crisis, this sober and elite separation from the reality of your investments must end. This bank must be interrupted by all citizens, all the time – to save our lives.’

I feel myself being pulled from my perch on a window seat. It’s time to go. I go on a bit more: ‘Stop banking, start living! This extinction wave is rising with your profit! What kind of economy depends on mass death?’

Now Nehemiah has got me by the polyester lapels: ‘It’s time. It’s been 15 minutes. Let’s get out of here.’ The toads are also having difficulty stopping their hopping. Several of our troupe are highly-trained underemployed method actors. Their hopping is so convincing you’d think their legs are 15 feet long. But Nehemiah is able to wade out into the pond we have created here and collar the toads. They finally do stop their hopping, take off their toad heads, and walk toward the silver moving stairs to descend.

“Okay, whatever your weird religion is, we’re taking you in.”

We re-cross the Avenue. It isn’t raining anymore. So much has happened that it feels surprising that the Manhattan Gourmet Restaurant is the same as it was when we left it, but that was only 20 minutes ago. They had kindly allowed us to leave our backpacks behind the counter, and now they let us reach over and grab our stuff. We say goodbye, and maybe we spend a little too much time with the hugs and thanks.

We go down into the subway, at perhaps too leisurely a pace. And the singers do manage to commute to freedom.

I fought the law...

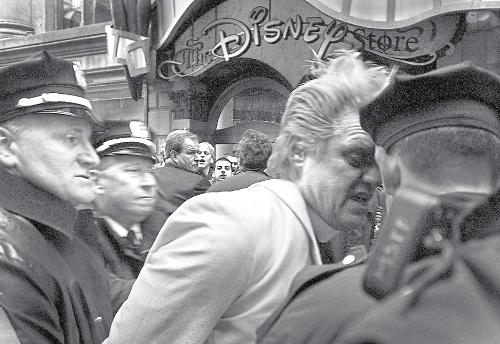

Nehemiah and I, however, are caught by the police on the station’s platform still holding our damning evidence, the sack of toad heads. We have six officers surrounding us. We’re cuffed in front of our fellow commuters and led away.

Escorted back up to the street, the police decide to leave us in the glass ATM lobby. The lunch hour crowd gawks at the black man and the sad preacher in handcuffs surrounded by now an incredible number of cops. Forty? Fifty? All these cops! – lots of New York’s Finest, standing there studying us.

Who knows how long we were there – a half hour?

More? I know that more people witnessed us standing there than come to a year’s worth of our shows at the Public Theatre. We gathered around us a sizeable group of mildly scandalized citizens, and a flotilla of police, cruisers with lights pumping. Nehemiah was amazing, laughing the whole time. He acted like it was a reality show.

More? I know that more people witnessed us standing there than come to a year’s worth of our shows at the Public Theatre. We gathered around us a sizeable group of mildly scandalized citizens, and a flotilla of police, cruisers with lights pumping. Nehemiah was amazing, laughing the whole time. He acted like it was a reality show.

One John Wayne-like cop, older and clearly in charge, came down on Nehemiah for his good humor. ‘You think this is funny?’ ‘Well, yes it is,’ I replied. ‘We are extinct animals in a protest.’ Nehemiah added: ‘Extinct animals who don’t appreciate being extinct...’ The white shirt looked at us like he’d bitten into a piece of bad meat. Then he jerked back to attention. ‘Okay, whatever your weird religion is, we’re taking you in.’

Finally, we were told to get our asses into the back seat of a cruiser, our handcuffs making us lie sideways. The precinct house for crimes committed in the Broadway and Times Square area is called ‘Midtown North.’ At 54th St and 8th Avenue, it wasn’t far away, but mid-town is a constant traffic jam so it took a while. John Wayne was already waiting for us when we got there, with his pen and forms laid out on the desk, ready to process us into jail. Bummer.

It could have been a more severe bummer. The police in the front seat, wending their way through the midtown traffic while we were pretzelled in the backseat, told us that a hysterical woman in the bank had locked herself in a bathroom and called 911, sobbing and retching and proclaiming that she wouldn’t unlock the bathroom door until the police arrived. ‘I need to save myself from bank robbers in animal masks...’

She incited a robbery-in-progress alert, a Code 19 went out, and police were running red lights all over Manhattan to get to our toad pond.

So, no, we didn’t think that was funny. That was not good. Somebody could have gotten hurt. We had thought we were being clear enough with our explanations and the comic appearance of the toad masks. We had thought that the singing, though certainly forceful, was also entertaining.

Nehemiah and I sat in the cell a while together, the sad cage rich with the smells of Times Square drunks and pickpockets.

We let out a long exhale, weighing the day’s blur of events.

Our softly spoken conversation had the oxygen burned out of it by the stare of Captain Wayne. And, we murmured to each other: we are... we are so in the system. John Wayne will put us so deep in Kafka world, that is to say, so deeply incarcerated in the city jail (known to locals as ‘the Tombs’), it ain’t funny. ‘Looks like we’re going downtown,’ I said. ‘The issue is not in doubt,’ answered Nehemiah, maestro of the singing toads.

Suddenly officer Beaudette, an old friend from our dozens of arrests downtown at Union Square, bursts into the police station. Beaudette plants himself between the sad prisoners and the triumphing moralist of stage and screen. ‘Hi Jack,’ says officer Beaudette. (Oh, maybe his name is John Wayne.) Then officer Beaudette sees us. ‘Billy! Another protest! That was you at the bank??!! How’s your daughter, she must be four now, right?’

Oh! Oh my god. Beaudette is the captain of Midtown North! He’s been stationed up here! When captain Beaudette indicated that he knew my family, that turned John Wayne into Robin Williams in Patch Adams. Well, maybe not that cuddly. But he stopped sending us to the Tombs at that moment. Resurrection Time! Officer Beaudette, a man who put me in the Tombs probably 20 times when he worked at the Union Square precinct, said: ‘Oh sign the Rev and his friend out. They’re good for their word. Get Rev back to Lena.’ And turning to me: ‘Got a picture?’

We had thought the toads would be like Disney characters, poignant and political for the people who did get it, and outlandish and comic for the people who didn’t. For those who did, well, those people would remember the natural world and connect their work in the bank to its consequences. But that lady in the bathroom unleashing the NYPD? She freaked out. That shouldn’t happen.

The show must go on

And a couple of months later, in court, the district attorney’s office imitated the upset woman. They called our action a ‘menace’ and a ‘riot,’ and urged the judges (a series of four of them over the next six months) to send Nehemiah to jail for three months, and said that I should go in for a full year.

Eventually, the assistant DA, a young crypto-yuppie type who had long ago abandoned himself to assholishness, told the last in the assembly line of Manhattan municipal judges: ‘Your honor, on further review we have determined that these are entertainment professionals and this was a musical presentation.’

Eventually, the assistant DA, a young crypto-yuppie type who had long ago abandoned himself to assholishness, told the last in the assembly line of Manhattan municipal judges: ‘Your honor, on further review we have determined that these are entertainment professionals and this was a musical presentation.’

Nehemiah walked. I was consigned to an afternoon of ‘community service,’ cleaning the benches and viewing area of the Statue of Liberty. I selfied myself with brooms and black rubber gloves and much love poured in on Twitter....

Postscript: We asked press professionals to estimate the number of ‘media exposures’ posted about this story of a musical, Earth-political action that had been staged inside a wealth management Chase Bank branch. The estimates were between 80 and 100 million exposures, and in a good number of these, the causal connection of Chase’s investments and climate change was stated in the first sentences of text. This was the case with NPR, and the Guardian, the Village Voice and Grist, Forbes and the Huffington Post.

Do we know if this media attention to the information offered up by a comic-political-spiritual (that is to say, very weird because un-categorizable) troupe in New York resulted in a significant number of customers pulling their money out of JPMorgan Chase? We have no way of knowing that. But we don’t expect measurable impacts from our work, not in this case.

The point is, most of us usually don’t think of banks as financing climate change. The process of education about this has barely begun. To change a critical mass of citizens on this issue, it will take far more evidence than we can present in one action, one trial, some press, and a run at the Public Theatre.

On the other hand, we successfully presented a civics lesson: this isn’t a question only of information, policy, litigation and lobbying – the solution must be spiritual. What we need is an escape from our habitual human-centred fundamentalism.

In the Church of Stop Shopping, we know that behind whatever campaign it is that we’re working on, the Earth whispers to us like the ultimate conscience: ‘There must be a change in how we imagine, express, sense life, and how we love.’