Nuclear promises

It is difficult to see the Crimea crisis clearly through the choking fog of western hypocrisy that surrounds it. Before trying to do so, there is one factor that we should deal with straightforwardly. When Ukraine became independent (after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991), it inherited 1,900 strategic nuclear warheads, more nuclear weapons than China, France and Britain held - combined.

If, instead of repatriating these weapons to Russia in the mid-1990s, Ukraine held those weapons today, it is extremely unlikely that Russia would have invaded the Crimea. This may be an uncomfortable truth, but we think it must be faced by those who want to advance nonviolence.

If we want to persuade smaller nations to remain free of nuclear weapons, as we should, as they should, we have to have answers to the questions that arise.

Ukraine gave up its weapons in return for a promise that its territorial integrity would be protected by the USA, Russia and the UK, under the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances. This agreement has manifestly not been honoured by any of the parties.

Strictly speaking, as Steven Pifer, former US ambassador to Ukraine, points out, the Budapest Memorandum ‘bundled together a set of assurances that Ukraine already held from the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) Final Act, United Nations Charter and Non-Proliferation Treaty’. Pifer observes: ‘The Ukrainian government nevertheless found it politically valuable to have these assurances in a Ukraine-specific document.’

The specific ‘security assurance’ given in the memorandum (not a treaty) was that ‘if Ukraine should become a victim of an act of aggression or an object of a threat of aggression in which nuclear weapons are used’ (emphasis added), Russia, the UK and/or the US would take steps.

Well, actually, just one step. The one action specified, in the case of a nuclear weapons-related security issue, was that they would ‘seek immediate United Nations Security Council action to provide assistance to Ukraine, as a non-nuclear-weapon State party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons’.

In any non-nuclear-weapon-related situation, Russia, Britain and the US promised only to ‘consult in the event a situation arises that raises a question concerning these commitments’.

The US and Britain have lived up to the words of the Budapest Memorandum (calling a ‘consultation’ meeting on 5 March which Russia refused to attend), while violating its spirit.

Former foreign minister of Australia Gareth Evans has argued that nuclear weapons would not have prevented the Russian invasion of Crimea: ‘weapons that would be manifestly suicidal to use are not ultimately a very credible deterrent’. In his view, Russian president Vladimir Putin would have known that Ukraine would not ‘nuke Moscow for sending tanks into Crimea, or even Dnipropetrovsk’. Yet at the same time, Evans himself points out that Ukraine’s possession of nuclear weapons would have added ‘another huge layer of potential hazard, owing to the risk of stumbling into a catastrophe through accident, miscalculation, system error, or sabotage.’

Evans is absolutely right to stress the terrifying risks and instability of ‘nuclear deterrence’, but it does no good for us advocates of disarmament to deny that invading a country that possesses nuclear weapons is a frightening prospect that no rational leadership would undertake.

This simple truth does not justify the possession of nuclear weapons, which remain immoral and illegal and dangerous to the survival of civilisation, if not humanity as a species.

An equally simple truth is that if Ukraine had retained its nuclear weapons in 1991, it might not have been invaded by Russia in 2014, because there is a good chance that in the intervening years an accidental or mistaken nuclear launch would have led to the devastation of both nations, along with neighbouring countries.

Setting Crimea in context

On 2 March, US secretary of state John Kerry reacted to the Russian invasion of Crimea by saying: ‘You just don’t in the 21st century behave in 19th century fashion by invading another country on completely trumped up pretext.’

Since Vladimir Putin’s first ascendancy to the Russian presidency in 2000, the Russian state has used its armed forces against other countries twice: against Georgia, in 2008; and now against Ukraine.

In the same time period, Britain has used its military forces without UN authorisation against four countries: Sierra Leone (2000), Afghanistan (2001-present); Iraq (2003-2008, officially); and Libya (2011). (In Libya, there was a UN-approved ‘no-fly zone’, but NATO forces exceeded this mandate). During these same years, France has attacked several African countries, some repeatedly, including: Côte d’Ivoire (2002, 2004, 2011); Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) (2003); Chad (2006, 2008); Libya (2011); Mali (2013); Somalia (2013); Central African Republic (2006, 2013-present).

The US has used its armed forces in a criminal fashion against a number of countries, including: Afghanistan (2001-present); Yemen (drone attacks, 2002-present); Iraq (2003-present); Pakistan (drone attacks, 2004-present); Libya (2011); Somalia (2011-present).

Some of these attacks may be classed as state terrorism, many amount to the crime of aggression.

The modern classic example of a ‘trumped-up pretext’ is, of course, the weapons of mass destruction alleged to exist in Iraq in 2003.

The 19th century is not over for these leaders of the free world.

The western powers are in no position to lecture Putin, whose actions in Crimea look like a Gandhian direct action when compared to the normal US-UK mode of operation. From 28 February to 18 March, Russian forces captured over a dozen Ukrainian bases or military posts without the loss of a single life. Compare this to the US use of tank-mounted ploughs to bury alive perhaps thousands of Iraqi conscripts in desert trenches during the opening moves of the 1991 invasion of Iraq. (US colonel Lon Maggart, in charge of one of the brigades involved, estimated that between 80 and 250 Iraqis had been buried alive.) Or the launching of two dozen cruise missiles at the outset of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, to try to assassinate Iraqi president Saddam Hussein and his lieutenants.

When one thinks of the number of deaths caused by US-UK aggression since 2000, including the grim ongoing tragedy of the Iraqi civil war, it is difficult to listen to the wave of western outrage.

This is not to deny that Putin has presided over a repressive administration, or that he has carried out many atrocities. Under his leadership, Russian forces carried out indiscriminate bombing of civilians (including with fuel-air explosives) in the southern Russian republic of Chechnya, followed by massacres and the enforced disappearance of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Chechens. It was his brutal success in Chechnya that gave Putin a springboard to jump from being prime minister to the presidency of Russia.

At the same time, when we consider the record of the US, Britain and France during the Putin years, it is frankly bizarre that they can sanctimoniously exclude Russia from the G8 over Ukraine without being met with derision. Michael McFaul, the outgoing US ambassador to Moscow, told the New York Times: ‘The G-8 was something they [the Russians] wanted to be part of. This for them was a symbol of being part of the big-boy club, the great power club - and the club of democracies, I might add.’

One would have thought that Putin’s atrocities in Chechnya and his two invasions would fully qualify him for the great power club, alongside the gangster nations that invaded Iraq and Afghanistan, attack other nations at whim, and reserve the right to assassinate anyone they choose, anywhere the world, at any time, using drone technology.

Not one inch

US pacifist David McReynolds has made a number of wise observations about the context for Putin’s actions, including the deep Russian fear of invasion - after three devastating invasions from western Europe.

Back in February 1990, under president George HW Bush, US secretary of state James Baker promised Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev that if he allowed a reunified Germany to become part of NATO, ‘NATO’s jurisdiction would not shift one inch eastward from its present position’.

To be more accurate, Baker offered Gorbachev a choice: ‘Would you prefer to see a unified Germany outside of NATO, independent and with no US forces or would you prefer a unified Germany to be tied to NATO, with assurances that NATO’s jurisdiction would not shift one inch eastward from its present position?’ Gorbachev indicated his preference for the latter option. The following day, 10 February 1990, West German chancellor Helmut Kohl met with Gorbachev, reassuring him that ‘naturally NATO could not expand its territory’ into East Germany, and his foreign minister, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, clarified that this meant not only East Germany, but the whole of Eastern Europe: ‘As far as the non-expansion of NATO is concerned, this also applies in general’.

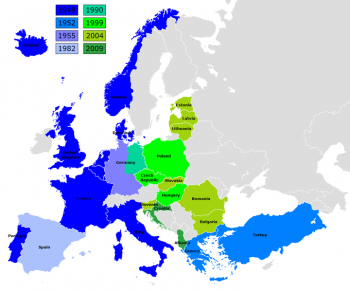

Unfortunately for Gorbachev, no written agreement was made, and since that date, 12 former Soviet bloc countries have joined NATO, including Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia - the latter three had been part of the USSR itself. NATO has been advancing towards Russia for nearly 25 years, and, from Putin’s point of view, Ukraine has been the last straw.

It is not well-known that the EU-Ukraine association agreement which triggered the crisis in Ukraine last year, was not just economic, but also military. Article 4, for example, talks of: ‘gradual convergence on foreign and security matters with the aim of Ukraine’s ever-deeper involvement in the European security area’; and article 10 promotes ‘military-technological cooperation’, which is a codeword for interoperability with NATO forces.

Under Russian pressure, the Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych rejected the agreement, which helped to trigger the crisis that led to his downfall and the installation of a government of ‘neoliberals and nationalists’ (Ukrainian sociologist Volodymyr Ishchenko). It was predictable that this government would move to sign the EU association agreement, as it has (though the bulk of the agreement will be signed in late May, after the presidential elections).

McReynolds comments: ‘Pause for a moment and assume that revolutionary events in Canada had meant Canada was about to withdraw from NATO and invite in Russian military advisers. What do you think US response would be?’ US international lawyer Richard Falk has suggested another analogy for the US: ‘if say a radical anti-American takeover took place in Mexico, and Russia was audacious enough to object to American extra-territorial interference, dire consequences would follow’. Falk notes that the US claims ‘a license to act against Russian borderland encroachments that would never be tolerated in reverse’.

To fine-tune the Falk analogy, let’s imagine a world in which the financial crisis happened in 1988 instead of 2008, and in which the US was forced into a major step down in its power and influence as a result. Let’s imagine that in 1990, the US accepted a Soviet offer to absorb a reunited Germany into the Warsaw Pact, in return for a promise that the pact would not extend its forces or its jurisdiction beyond the existing boundaries. Let’s imagine that in the intervening years, the Warsaw Pact continued to exist, and in fact expanded into Latin America, so that most states, from Argentina to Honduras, became members of the pact, with the rest being in ‘Partnerships for Peace’ with the Soviet-led military alliance. In these circumstances, how would the US react to ‘a radical anti-American takeover in Mexico’, deposing a staunchly pro-US president?

The analogy makes no sense, of course, because the US would never have accepted the inclusion of a reunited Germany into the Warsaw Pact, and would have responded with massive violence as soon as a Latin American state began allying with the Soviet Union informally, let alone joining the Warsaw Pact. The decades of US terrorism against Cuba are evidence of that.

Not a fascist coup

Bearing in mind all this context, we can approach some of the actual events. There is a worryingly-common tendency in the anti-war movement to see the mass rebellion in Ukraine as a western plot, and the new government as a fascist takeover. The evidence is just not there.

As Stephen Zunes, a US specialist in people power movements, has noted, those who overthrew Yanukovych were ‘primarily liberal democrats’ engaged in nonviolent resistance, though the movements ‘included - though were not dominated by - armed, neo-fascist militias’.

Zunes observes that the US has not spent $5bn to destabilise Ukraine - most of this money has gone to pro-Western administrations the US has wanted to shore up. He points out that the millions, not billions, in funding that the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and other US institutions have given to Ukrainian opposition groups have gone ‘primarily to centrist groups, not the far right’.

When you look at the NED’s list of grants to Ukrainian groups, the major recipient is the Centre for International Private Enterprise (an NED core institute), supporting Ukrainian business associations ($359,945). The next biggest recipient is the International Republican Institute ($250,000), supporting Ukrainian political parties’ involvement in the October 2012 parliamentary elections: improving voter targeting, message development, candidate-recruitment, coalition-building, and access to public opinion research. The IRI also got two big grants ($95,000 and $35,000) to support Cherkasy municipality develop and implement best practices in local government. The two biggest direct grants to European groups went to the (Ukrainian) Democratic Initiatives Foundation ($73,464 for ‘debate and dialogue’, including three dozen surveys, roundtables and publications); and the (Polish) East European Democratic Centre (two grants of $78,969 and $41,584 for support to local non-state newspapers, and training seminars for 56 local civic activists, respectively). Almost all the other grants are in the $30,000 region, to groups such as the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, and the voter education project of the ‘Moloda Cherkaschyna’ Coalition of Cherkassy Youth NGOs. Sponsoring a fascist coup, this is not.

Zunes comments that former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych’s ‘rampant corruption, repression, and divide-and-rule tactics had cost him his legitimacy in the eyes of the majority of Ukrainians’: ‘The protesters were primarily liberal democrats who engaged in legitimate acts of nonviolent resistance against severe government repression, many of whom spent months in freezing temperatures in a struggle for a better Ukraine dominated by neither Russia nor the West. To label them as simply puppets of Washington is as unfair as labeling peasant revolutionaries in El Salvador as puppets of Moscow.’

It's absolutely true that the US has destabilised several countries since the Second World War, including by organising coups d’etat. However, there is a great difference between what has happened in Ukraine and what happened in Chile in 1973 (covert economic warfare and fomenting a military coup) or Iran in 1953 (hiring gangs to pretend to be Communists and anti-Communists fighting each other, to create a sense of chaos, and fomenting a military coup). In Ukraine as in a host of other countries in recent decades, including the phenomenon of the Arab Spring, there was a mass citizen uprising, something that cannot be bought with CIA dollars or organised behind closed doors.

Just as the movements who overthrew Yanukovych ‘included - though were not dominated by - armed, neo-fascist militias’ (Zunes), the new Ukrainian government similarly includes but is not dominated by ultra-right figures. While official positions are held by individuals from two separate neo-fascist outfits, the political party Svoboda and the grouping known as Right Sector, the Huffington Post has pointed out that ‘the political and ideological make-up of Ukraine’s opposition-turned-government is far more complex and nuanced, and includes a practicing Jewish businessman and a campaigning Muslim journalist.’

On 4 February, some weeks before the Russian invasion, 41 specialists in the field of Ukrainian nationalism studies (half of them based in Ukraine itself) issued a joint statement to journalists and other commentators, protesting against the misrepresentation of 'the role, salience and impact' of the Ukrainian far right within the Ukrainian rebellion. The specialists wrote that: 'the movement as a whole merely reflects the entire Ukrainian population, young and old. The heavy focus on right-wing radicals in international media reports is, therefore, unwarranted and misleading.'

At the time of writing [9 April]], Svoboda have four cabinet positions (including deputy prime minister), and are thought to have an excellent springboard to expand their narrow social base (they won 10 per cent in the 2012 parliamentary elections), given the nationalist backlash against the Russian invasion, and the fury that will follow the IMF-imposed austerity programme that is part of the EU association agreement. Russia and the EU are in effect co-operating in creating the best conditions for the growth of Ukrainian neo-fascism.

The Un-Referendum

For people who believe strongly in the right of secession, the Russian annexation of Crimea can appear complicated. If the majority of people in Crimea wanted to leave Ukraine and join Russia, then the Russian invasion might be seen as a procedural error rather than a criminal act.

For people who believe strongly in the right of secession, the Russian annexation of Crimea can appear complicated. If the majority of people in Crimea wanted to leave Ukraine and join Russia, then the Russian invasion might be seen as a procedural error rather than a criminal act.

However, if the majority of people in Crimea wished to separate from Ukraine and become part of Russia, that was a matter for them to pursue, within Ukraine, just as nationalists within Scotland have pursued separation from the United Kingdom, within the UK. It cannot become part of international practice for country A to decide all by itself that an ethnic minority in country B would be better off under A's rule, or would prefer to be part of A's state, and then to invade B on that basis.

As it happens, the polls taken in Crimea in the year before the Russian invasion do not support the idea that most Crimeans wanted to re-join Russia (the republic was detached from Russia only in 1954). Two polls in early 2013, long before the protest movement got under way, give confusing results, but both show a minority of Crimeans identifying as Russian. A Gallup poll in May 2013 found that 40 per cent of Crimeans considered themselves 'Russian' as opposed to 'Crimean' (24 per cent), 'Ukrainian' (15 per cent), or Crimean-Tartar (15 per cent). A January 2013 poll by the Razumkov Centre found that only 1 per cent of people in Crimea spontaneously identified their homeland as 'Russia' - a further 10 per cent said 'the Soviet Union', which had not existed for over a decade.

The question of personal identity doesn't necessarily map exactly onto the political direction one wants for Crimea.

Five years earlier, in 2008, the Razumkov Centre in Ukraine found 'confusion and inconsistency' on this question across all age, confessional and ethnic groups in Crimea:

'the majority of Crimeans would like Crimea to secede from Ukraine and join Russia (63.8%), and at the same time – to preserve its current status, but with expanded powers and rights (53.8%). More than a third (35.1%) would like it to become a Russian national autonomy as a part of Ukraine; also more than a third (34.5%) – to secede from Ukraine and become an independent state.'

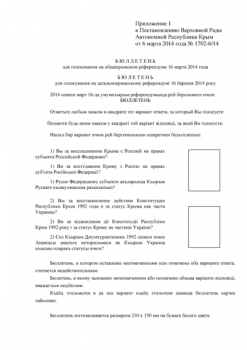

Even if 63 per cent of Crimeans had wanted, in February 2014, to leave Ukraine and join Russia, this would not have justified the Russian invasion. This would not have justified Russia managing its own referendum in Crimea (officials reported an 80 per cent turn out, and 93 per cent approval for seceding and re-integrating with Russia, which are frankly unbelievable numbers).

Anti-war activists have opposed referendums and elections under US occupation in Iraq and Afghanistan. We should apply the same standard to the Russian occupation of Crimea.

Dissolve NATO

What is the path away from war? US pacifist David McReynolds remarks that the best response to the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 would have been to offer to dissolve the military alliances that divided Europe: ‘What if we had said to Moscow, withdraw your tanks from Hungary, and we will dissolve NATO, while you dissolve the Warsaw Pact.’

What is the path away from war? US pacifist David McReynolds remarks that the best response to the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 would have been to offer to dissolve the military alliances that divided Europe: ‘What if we had said to Moscow, withdraw your tanks from Hungary, and we will dissolve NATO, while you dissolve the Warsaw Pact.’

Today, there is no Warsaw Pact, but the same logic holds. Putin’s aggressive Russian nationalism has popular support because of western encirclement. There are many Russians who oppose his foreign policy (including the 50,000 who demonstrated in Moscow on 15 March), but to others, Russian imperialism feels like a defensive strategy. This is part of why Putin's approval ratings have increased from 60 per cent in January to 82 per cent at the end of March, according to one polling group. (Despite the fact that, according to another pollster, only 15 per cent supported the idea of Russian intervention before it happened.) To start to undo Russian imperialism, we need to undo US/NATO imperialism and dissolve the military alliance that has advanced to the borders of Russia.

The Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea are criminal acts that should be reversed. While the western powers are in no position to give moral lectures about the sanctity of national borders, given their track record of attacking other countries, they should do what they can to help Ukraine regain control of its own territory. One thing they could do is to pledge that NATO will not accept Ukraine as a member. They could go further and dissolve the NATO military alliance entirely. These steps could be part of a diplomatic process that includes the withdrawal of Russian forces from the border with Ukraine, a reversal of the Russian annexation of Crimea, a genuine referendum on the future of the republic, and a wider demobilisation and disarmament process.

Guaranteeing the neutrality of Ukraine, as Russia has asked, would be to finally, start making good on James Baker’s ‘not one inch’ pledge of 1990.

NATO is a machine for facilitating or imposing western domination on the rest of the world. Dismantling it would be a valuable step towards a more peaceful world, and a valuable de-escalatory move in the current crisis.