How should a white anti-racist respond to racist remarks by another white person? How does it change things if the anti-racist is middle-class, and is reacting to the prejudice of someone who is working-class?

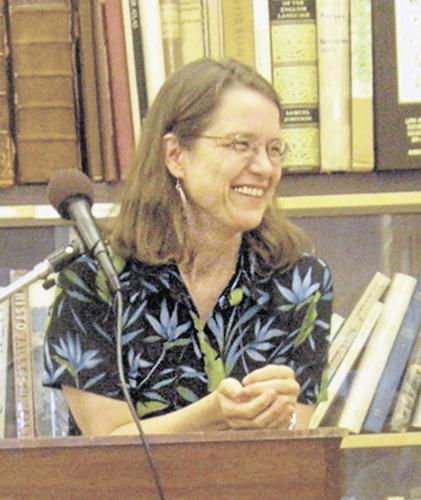

In her book Class Matters, long-time activist and trainer Betsy Leondar-Wright tells an arresting story that turns the conventional wisdom on its head. Betsy, who is white and middle-class, was the organiser for an anti-nuclear power group in a mixed-race, mixed class neighbourhood. The only working-class person in the group was a white man she calls ‘Tom’, a smart and dedicated member of the group.

‘I don’t like black people’

One day, in the car on the way to a demonstration, Tom said: ‘I don’t like black people and black people don’t like me.’

Betsy was stunned. Where most of us would go with judgement, her response started from curiosity. What experiences had Tom had with black people? Tom had grown up in a white neighbourhood that gradually changed into a black one, with a small group of low-income white families left behind, and a small white gang of teenagers fighting black gangs every day.

Betsy just listened. Later, the two talked again about these experiences. Tom never made any negative generalisations about black people, ‘and was never disrespectful to the few black members of our group’. He just kept saying: ‘They didn’t like me, and I didn’t like them’.

At the end of each conversation, Betsy would say calmly that she had a different impression of black people, and told him stories of her friendships and activist experiences with African-Americans. From what I can make out, she made no attempt to immediately persuade Tom or criticise him.

The next move I find breath-taking. A few weeks later, the group spent a Saturday collecting signatures for a petition. Betsy paired Tom up with a gentle, soft-spoken black gay man. She gave them an area lived in by elderly lower-middle-class African-American homeowners.

At the end of the day, Betsy asked Tom how it went. All he said was: ‘I’m a sucker for old people.’ Betsy writes: ‘But I never heard him say anything about disliking black people again.’

“I can boil this down to two words: I was respectful and engaged.”

The story doesn’t end there. Betsy moves away, then comes to visit six months later. She saw Tom. I have to reprint all of this:

‘The minute he saw me, he was bursting with a story: “Betsy, listen to what I did! This guy who worked at the garage was really prejudiced against black people, always saying nasty stuff. So one time there was a tow job, and I had to send two guys on a really long drive. So I sent this prejudiced guy along with this really nice black guy, and by the time they got back they were, like, friends, and now he doesn’t say that shit any more!” He was beaming at me. I laughed and hugged him and told him he did good.’

Betsy draws out what she did right in this situation.

- She never let go of her liking and respect for Tom as a fundamentally good person.

- She listened first, learning his story.

- She didn’t let it slide: ‘I took it as intolerable that this energetic activist would be stuck believing harmful misinformation because of his past. I figured out something to do about it, something that gave him some credit for having some intelligence and ability to figure things out for himself.’

- She gave it time, spending weeks simply sharing her different multicultural experiences before directly saying she saw a problem with his racist comments. ‘It’s one of the few times I’ve ever stuck to the “I-statement” groundrule in the face of a vehement disagreement.’

Elsewhere, Betsy writes: ‘Build your relationships not just with people targeted by the oppressive speech, but build a relationship with the offender too, and speak to them humbly like someone who has also said oppressive things in your life, as we all have.’

This being Betsy Leondar-Wright, she is painfully honest in relating this story: ‘I can boil this experience down to two words: I was respectful and engaged.... Far more often, I’ve been closed and judgmental.’

The classism of ‘calling out’

Being ‘closed and judgemental’ can appear in activist circles as ‘calling out’. Talking to PN, Betsy describes this as: ‘The idea that the second something is said that is perceived to be insensitive or oppressive, it’s incumbent on you as an ally, or as somebody targeted by the oppression, to immediately speak, and name the person who’s done the wrong thing and what’s wrong with it, immediately, in front of the group.’

Betsy is fully on board with following up when something oppressive happens, but she sees major problems with this kind of response.

She says George Lakey has been ‘brilliantly eloquent’ in identifying calling-out as a class issue (the first person to see it that way): ‘He thinks people are learning this at elite colleges where you’re taught to sit in judgement and be very critical of other people.’

George writes in Facilitating Group Learning: ‘what is the system that is preoccupied with sorting, screening, correcting, and grading, to make sure that people get in line? One system I know like that is class society.’ In which it is the job of the middle class to manage the workers.

Drawing on decades of training and activism, George notes: ‘The participants who most often take on this role [of policing and calling out oppressive behaviour] are, significantly, from middle or owning class families or, if working class, have graduated from college and absorbed the values of management and control.’ (George himself is working class, with a university education.)

George goes on: ‘The abstract character of the norm of calling out is itself a giveaway. The calling out norm is not based on life experience about what works [in changing people’s attitudes].... Calling out is based instead on the supervisor’s duty of correction.’

In other words, calling out is part of professional-middle-class culture. It is, in George’s words, another way that ‘classism undermines learning’.

Back in our interview, Betsy describes the results of calling out: ‘It’s shaming people. The most common response is the person who’s “called out” quits the group and never comes back. Not useful at all. Other people get extremely cautious, and use jargon that they don’t really even understand, or just don’t bring up anything at all.’

“Go after that person who said the offensive thing. Form a relationship with them. Invest.”

Betsy switches between her mainstream and her marginal identities to make clearer the humbler approach to anti-oppression work that she favours: ‘Speaking as a white person, all of us white people, there’s stuff that we don’t get about racism. I know with sexism and homophobia, where I’m the target [as a woman and a lesbian], of course people blow it! It happens all the time. But I don’t think there’s two kinds of guys: the sexist guys and the “good ally” guys. It’s a continuum! Everybody makes mistakes, most people have good will and are gradually raising their consciousness.’

In these kinds of situations, Betsy argues, it’s particularly important to take care ‘if you’re in a more privileged position and you’re dealing with a less-experienced activist, but especially with working-class and poor people when a college-educated person is thinking that something is oppressive.’

Betsy observes: ‘half the time it’s a misunderstanding or just some jargon somebody doesn’t know.’

In contrast to ‘calling out’, there is ‘calling in’. Betsy says: ‘a lot of the people who are saying we should be “calling in” instead, are women of colour, some of whom come from working-class backgrounds, who are, like: “Go after that person who said the offensive thing. Form a relationship with them. Invest.”’

And this is the point in the interview where Betsy raises the story of Tom, and what she did well in befriending him and giving him the opportunity to change his mind about black people. That was ‘calling in’.

In Class Matters, Betsy ends this section by crediting Tom with the rare willingness to let someone else teach him something, as well as the admirable ability to pass on the same gift to someone else.

Her final words remember ‘the African American man who spent the day working with someone he may have suspected of having prejudices against him and whose charm worked the magic.’