In 1832 a major outbreak of cholera struck London. According to a government report, it was 'proof of the judgement of God among us'. With this in mind, a 'National Fast Day' was proposed, with the aim of preventing the spread of disease. The irony wasn’t lost on the poor. The National Union of the Working Classes 'encouraged its supporters to enjoy a "Feast Day" which, it argued, would benefit the poor far more.' After all, they had precious little to eat in the first place!

In 1832 a major outbreak of cholera struck London. According to a government report, it was 'proof of the judgement of God among us'. With this in mind, a 'National Fast Day' was proposed, with the aim of preventing the spread of disease. The irony wasn’t lost on the poor. The National Union of the Working Classes 'encouraged its supporters to enjoy a "Feast Day" which, it argued, would benefit the poor far more.' After all, they had precious little to eat in the first place!

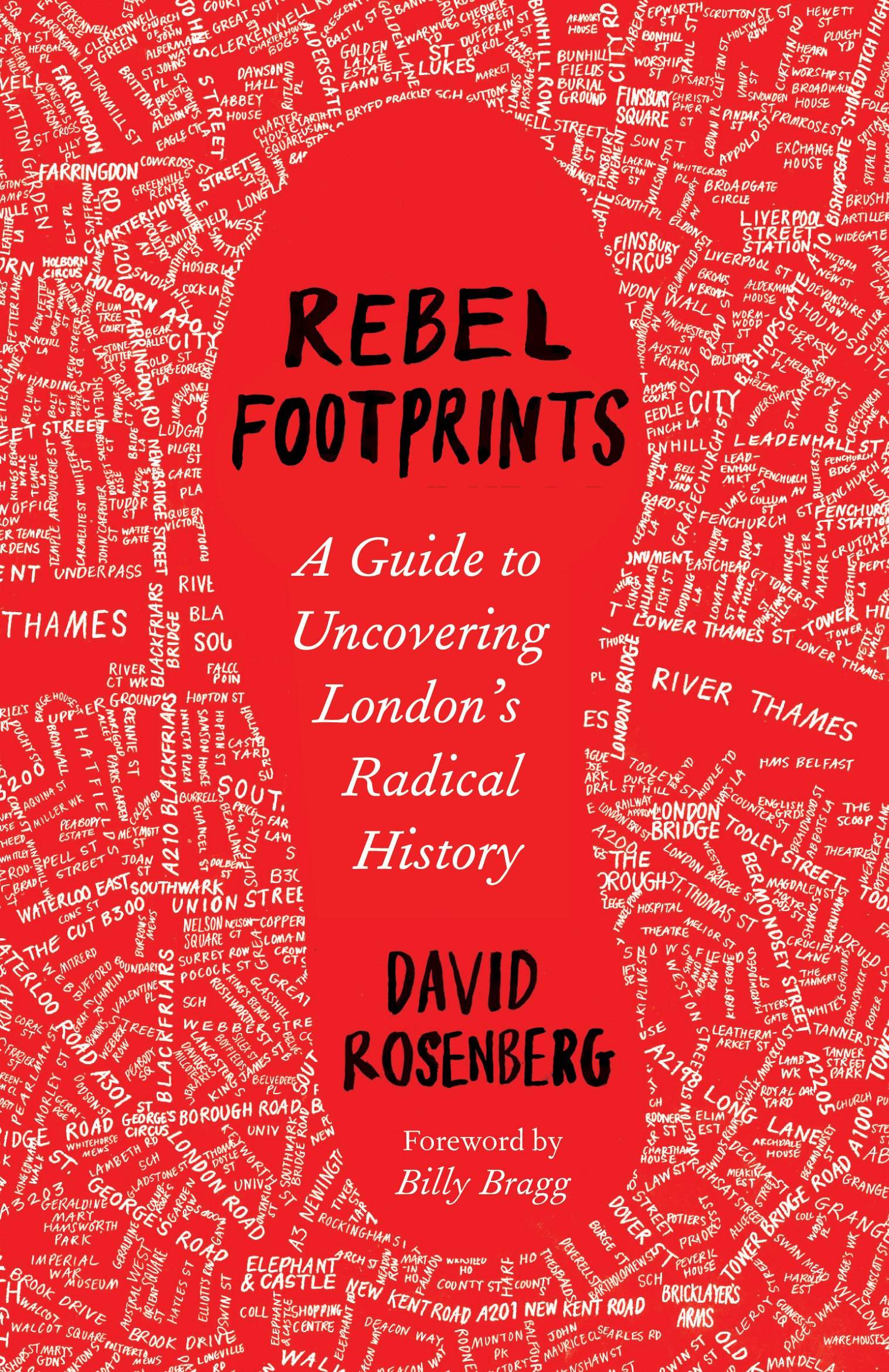

Covering the period of 1830 - 1930, Rosenberg’s lesson is that despite today’s struggles, we should be grateful for the victories claimed by those before us which have freed up daily life.

Rosenberg gives an outline of what has been won, and it’s worth quoting in full. After 1930: 'Trade unions were an accepted part of society; the Labour Party was a mass party seeking redistribution of wealth, whose members were drawn largely from the working class; there was free universal education, and higher educational opportunities were about to expand . . . all female and male adults could vote, basic freedoms were guaranteed . . . The post-war Labour administration brought in further radical reform . . . demanding greater fairness, democracy and equality of opportunity.' Moreover, fascism was in severe decline, both domestically and internationally.

Traces of these victories remain in the streets of London, despite their disfiguration and masking by overly-influential corporations and deferential councils.

The plight of dockworkers is well documented. Work was hard to come by: 'a "day’s work" usually comprised less. Dockworkers often walked great distances to a job, unloaded cargo non-stop for two hours, and were then told to go home.' It was for one docker 'a 40-mile round trip on foot'.

In just these two examples you get an idea of the astonishing scale and variety of injustices and cruelties inflicted on London’s working class in the not-so-distant-past.

An ironic eye is cast on the charity of paternal 19th-century groups. The biography of mid- nineteenth-century activist Annie Besant argues that such charity 'plunders the workers of the wealth they make, and then flings back at them a thousandth part of their own product as charity. It builds hospitals for the poor whom it has poisoned in filthy courts and alleys.'

The size and depth of London means that this comprehensive book is dizzying in its accounts of worker and gender oppression. With this in mind, Rosenberg gives a walking tour at the end of each chapter - an essential tool for the understanding of London’s radical past.

Topics: Radical lives, Activist history