The debate about why the Labour party lost the Westminster election matters to everyone struggling for social change in Britain. How this fiasco is understood affects our confidence and our strategies (more on this below) – whatever our attitudes to the Labour party.

If it was true that Ed Miliband’s pale blue austerity-lite Labourism was too radical for the British people, that would drastically limit our ambitions.

When we look at the evidence, though, there is no reason to believe Tony Blair’s claim that Ed Miliband went ‘too far left’.

There’s no reason to accept Blair’s decree that Labour – or anyone wanting change – needs to accept ‘solutions’ that ‘appeal to those running businesses as well as those working in them’, and that ‘cross traditional boundaries of left and right’.

There’s no reason to believe Blair, or Peter Mandelson, or former Labour home secretary Alan Johnson, or current leadership front-runner Andy Burnham, when they insist that successful progressive politics must start by celebrating individualist, pro-business ‘aspiration’.

Nothing to do with it

We now know that ‘Labour’s perceived hostility to aspiration’ did not contribute to its unexpected election loss.

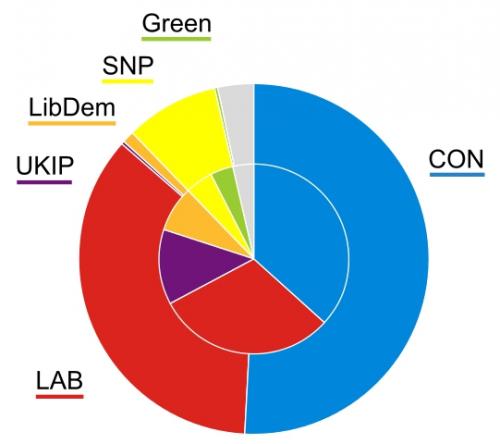

We know this because the TUC ran a poll of 4,700 people from 8–12 May. This found that of seven possible reasons for rejecting Labour, the least important to voters (just 10 per cent opted for this) was that Labour was ‘hostile to aspiration and success’.

The most important reasons for rejecting Labour were that they couldn’t be trusted with the economy (40 per cent) and that they were too easy on benefit claimants (25 per cent).

The third reason given was that a Labour government would be ‘bossed around by Nicola Sturgeon and the Scottish Nationalists’ (24 per cent).

No success like a failure

Labour right-wingers and the mainstream media talk about Ed Miliband as though he drove voters away with his extreme left-wing proposals.

Firstly, his platform was far from being left-wing (he didn’t even go for full nationalisation of the railways, which has overwhelming public support, including just over half of all Conservative voters).

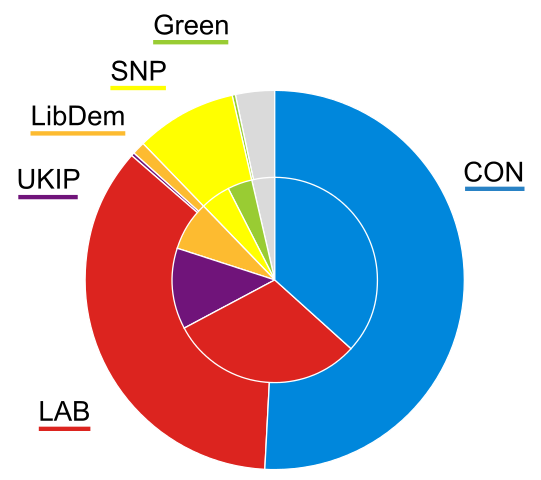

Secondly, Miliband increased the Labour party’s votes total (by 737,800) and its share of the vote (by 1.4 per cent) from 2010.

The Tories increased their number of votes by 608,000 (less than Labour’s 737,800), and their share of the vote by 0.8 (less than Ed’s 1.4) per cent.

The problem was that the Conservatives’ smaller gains were focused laser-like in exactly the right constituencies, so that overall they took 24 more seats than in 2010.

Because Labour’s increase in votes was in the wrong places (and we have an appalling electoral system), even though the Labour gain in votes was bigger than that of the Tories, it translated into 26 fewer Labour MPs than in 2010.

Popular policies

Blair acknowledged, in his election post-mortem, that many of Ed Miliband’s policies had been popular. Blair still warned against ‘an accumulation of policies, even if individually popular, that, taken together... send us too far left’.

The TUC poll mentioned earlier, run by Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research (GQRR), confirmed the popularity of many Miliband commitments.

A partner at GQRR, James Morris, summarised some of his findings in the New Statesman: ‘By 11 points, voters are more likely to support Labour raising tax on the rich than criticise Labour for risking driving investors abroad. Voters are 20 points more likely to think Labour is too soft on big business and the banks, than too tough.’

The voters didn’t support Labour’s approach to austerity: ‘by a 5 point margin voters thought Labour should cut spending more slowly than they planned rather than faster’.

Disappearing ‘considerers’

The TUC wanted to investigate the views of two overlapping groups of people: those who ‘seriously considered’ voting Labour, but didn’t; and those who voted Labour in 2010, but didn’t vote for them this time.

These are important groups of people for understanding how Labour lost. The ‘considerers’ may have boosted Labour in the opinion polls, without in the end turning out for them.

According to the TUC/GQRR poll, of the 2010 voters that Labour lost, over a fifth didn’t vote at all this time.

The number of considerers (which includes the ‘lost from 2010’) was nearly double that.

If we look at all voters, only 27 per cent thought Labour could look back with pride on its record in office. If we take just ‘considerers’, only 36 per cent thought Labour had ‘a good track record in government’.

James Morris of GQRR concludes: ‘In voters’ eyes, Labour’s problem over the last five years was too little change, not too much.’

So much for the Blairite insistence on ‘returning to the centre ground’.

The SNP scare

For the considerers, the three factors that most attracted them to Labour were:

- ‘They are more on the side of ordinary working people’ (48 per cent);

- ‘They would improve the NHS’ (44 per cent); and

- ‘They would do more to tackle inequality’ (27 per cent).

The three factors that put them off Labour in the end were the same as for voters as a whole (mentioned above), but it’s interesting that the SNP factor is much more important for this group than for voters as a whole:

- ‘They would spend too much and can’t be trusted with the economy’ (30 per cent down from 40 per cent for voters as whole);

- ‘They would be bossed around by Nicola Sturgeon and the Scottish Nationalists’ (29 per cent, up from 24 per cent for voters as a whole); and

- ‘They would make it too easy for people to live on benefits’ (26 per cent, up from 25 per cent).

In other words, the Conservatives’ scare campaign about a weak minority Labour government relying on SNP votes in parliament was very effective in putting people off voting Labour in the final days of the election campaign.

One way of looking at the the other two main factors is that Labour hadn’t, over the years, challenged either the assumptions of the Tory austerity programme, or right-wing lies about benefit claimants.

Realistic idealism

The poll shows that Labour hadn’t made enough of a break from its New Labour past, that its ‘pro-ordinary working people’ agenda was popular, and that people thought it was too soft on big business, not too left-wing.

The poll doesn’t show, however, that if Labour had been more radical it would have won the election. By a margin of 77 to 15, voters told GQRR they wanted parties to offer ‘concrete plans for sensible changes’ not ‘big visions for radical change’.

Those of us committed to social change (inside or outside the Labour party) are faced with the challenge of creating ‘concrete plans’ for ‘radical change’.

One way of looking at this is that we need to ‘expand the floor of the cage’. This phrase comes from the Brazilian rural workers’ movement, but in the UK is probably associated most closely with Noam Chomsky.

The ‘cage’ is the state, and inside it is the general population, which is oppressed by the state, but which cannot afford to join in the right-wing attack on the state, because outside the cage are even more destructive predators. These privately-owned corporations (often transnational) are completely unaccountable and, if freed from state constraints, would likely eliminate human society and much of the environment.

Chomsky observes: ‘You have to protect the cage when it’s under attack from even worse predators from outside, like private power.

‘And you have to expand the floor of the cage [with needed reforms], recognizing that it’s a cage. These are all preliminaries to dismantling it. Unless people are willing to tolerate that level of complexity, they’re going to be of no use to people who are suffering and who need help, or, for that matter, to themselves.’

Climate not Trident

Another finding in the TUC/GQRR poll was that, by 67 to 25, voters think that getting people into work and raising wages is a better way to reduce inequality than simply taxing the richest and sharing out the proceeds.

This fits in with our interpretation of the One Million Climate Jobs demand, and the way that this could support a programme of economic conversion and disarmament, particularly of the Trident submarine system. The skills needed for submarine-building are the same ones needed to develop wave power.

Fighting austerity, inequality, poverty, climate change and militarism all at the same time – while also building in more of a say in what goes on for the people who do the work.

What’s not to like?